Warning: This article contains some graphic content.

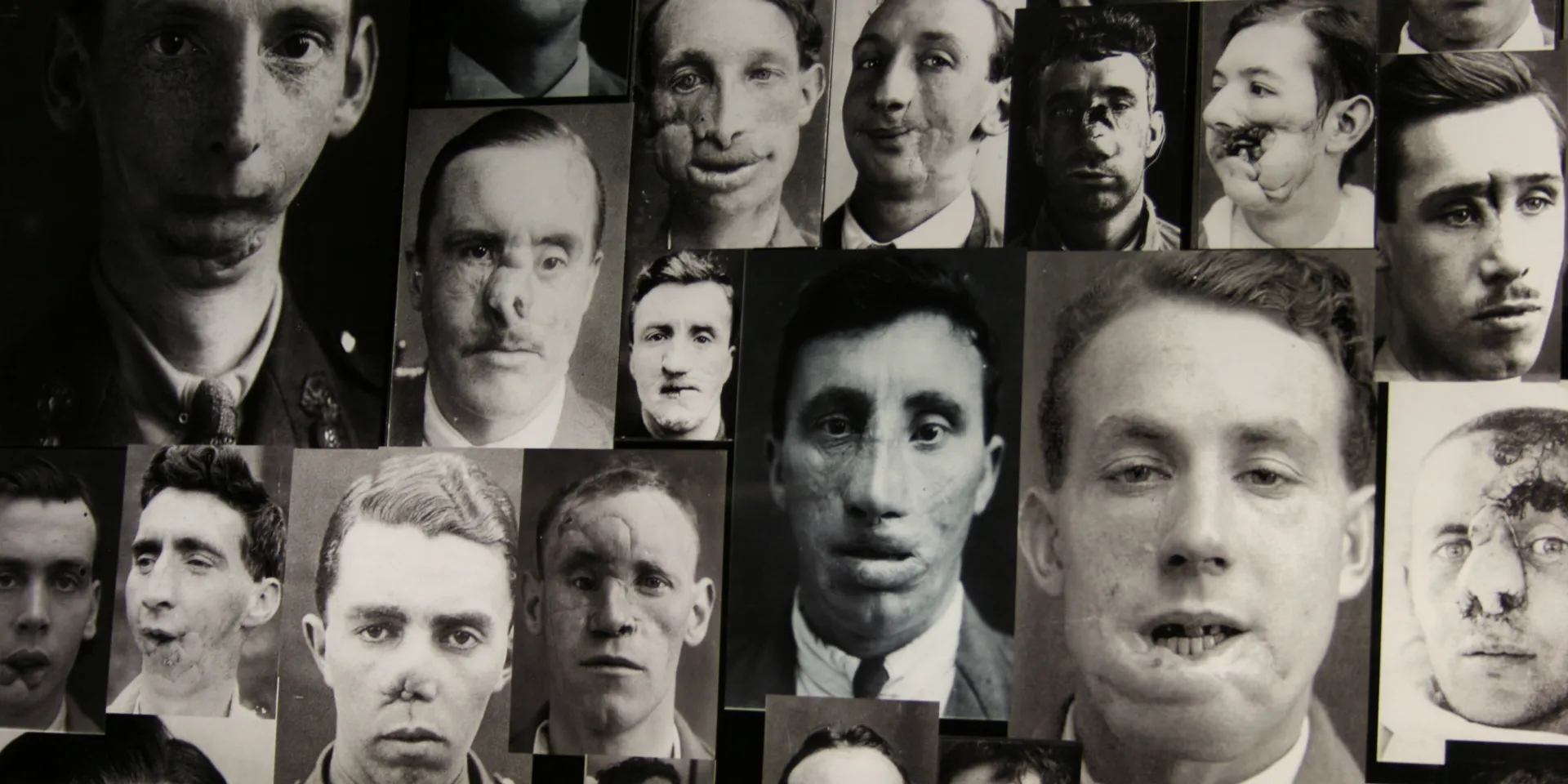

Collage of First World War facial injuries

The problem

Until the First World War (1914-18), most battle injuries were caused by small arms fire or sword cuts. Facial injuries were often of little concern to survivors who were deemed lucky enough to have escaped with their lives.

Weapons used during the First World War like heavy artillery, machine guns and poison gas, created injuries of a severity and scale unseen before. The circumstances of trench warfare, with men peering over parapets, caused a dramatic rise in the number of facial injuries sustained by soldiers.

Shells filled with shrapnel were to blame for many of these facial and head wounds, as they were specifically designed to cause maximum damage. Hot flying metal could tear through flesh to create twisted, ragged wounds or even rip faces off entirely.

'The floodgates in my neck seemed to burst, and the blood poured out in torrents... I could feel something lying loosely in my left cheek, as though I had a chicken bone in my mouth. It was in reality half my jaw, which had been broken off, teeth and all, and was floating about in my mouth.'John Glubb, hit by a shell fragment in August 1917

Early treatment

Facial injuries were not easily treated on the front line. Surgeons would sometimes stitch together a jagged wound without taking into account the amount of flesh that had been lost.

As the scars healed, the flesh tightened, pulling the face into a hideous grimace.

Jaw injuries could leave men unable to eat or drink. Some men had to be nursed sitting up to stop them from suffocating when they lay down. Others were blinded or left with a gaping hole where their nose used to be.

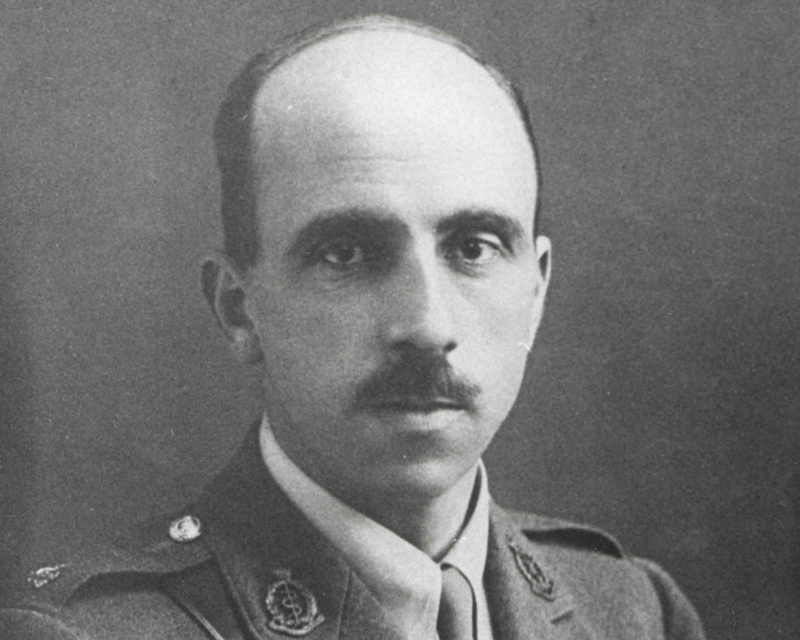

Harold Delft Gillies (© The Collection of British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons)

A pioneering surgeon

Harold Gillies was a New Zealand surgeon who had trained in England. Posted to France in 1915, he witnessed the rise in horrific facial wounds inflicted by this new style of warfare.

On his return to England, Gillies set up a special ward for facial wounds at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot. He even sent his own casualty labels to the field hospitals in France to make sure that men with such injuries were sent directly to him.

By 1916, Gillies had persuaded his medical chiefs that a dedicated hospital for facial injuries was required to meet the demand.

Gillies established The Queen’s Hospital at Frognal House in Sidcup in 1917. It was the world’s first ever hospital dedicated to the treatment of facial injuries.

The Queen’s Hospital

The aim of The Queen’s Hospital was to reconstruct wounded men’s faces as fully as possible, so that they could hopefully lead a normal life. Many patients lived in fear of what their loved ones would say when they saw how badly disfigured they were.

Gillies knew that healthy tissue needed to be moved back to its normal position. After this, any gaps could be filled with tissue from elsewhere on the body. Surgeons already had a degree of experience with skin grafts. And after the work had been completed on the bone structure of a man’s face, they were ready to reconstruct the soft tissues.

Skin grafting

One of the most successful skin grafting techniques was to release and lift a large flap of skin, called a pedicle, from near the wound. Still connected to the donor site, the free end of the skin flap would then be swung over to the site of the injury, without completely severing the connection to the body.

Maintaining the physical connection ensured that blood was supplied to the skin, increasing the chances of the graft being accepted by the body.

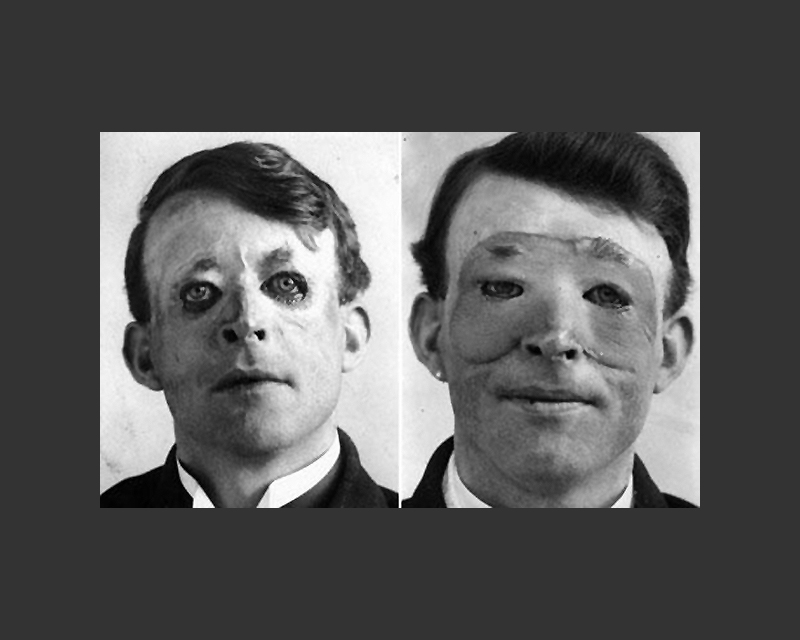

Walter Yeo, before (left) and after (right) skin flap surgery performed by Gillies in 1917 (© The Collection of British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons)

‘It was Gillies’ intention to take a strip of skin from my forehead and after lifting it to twist it downwards over the site of my nose to be, and at the same time to get some cartilage from me elsewhere to form the bridge of my nose.’Captain Budd, wounded in a shell blast — 1918

New techniques

Gillies puzzled over how to ensure that larger skin grafts could be accepted over the site of the injury, until he operated on Willie Vicarage. Willie had been badly burned in a fire during the Battle of Jutland (1916). His face was left as a fixed scarred mask and he couldn't shut his eyes or mouth.

Gillies proposed to raise a ‘Masonic Collar Flap’ of skin from Willie’s chest to repair the lower part of his face. During the operation, Gillies noticed that the edges of the pedicle flaps curled in on themselves under tension. He decided to sew them into a tube and found that the risk of infection was reduced and the blood supply was much better.

Once the tubed pedicle had become firmly attached near the site of the injury, it could be cut away from the donor site, opened and spread out to graft a much wider area if required.

This pioneering work by Gillies and his team marked a huge advance in reconstructing the faces of severely injured men. It also laid the foundations of modern plastic surgery.

Sharing knowledge

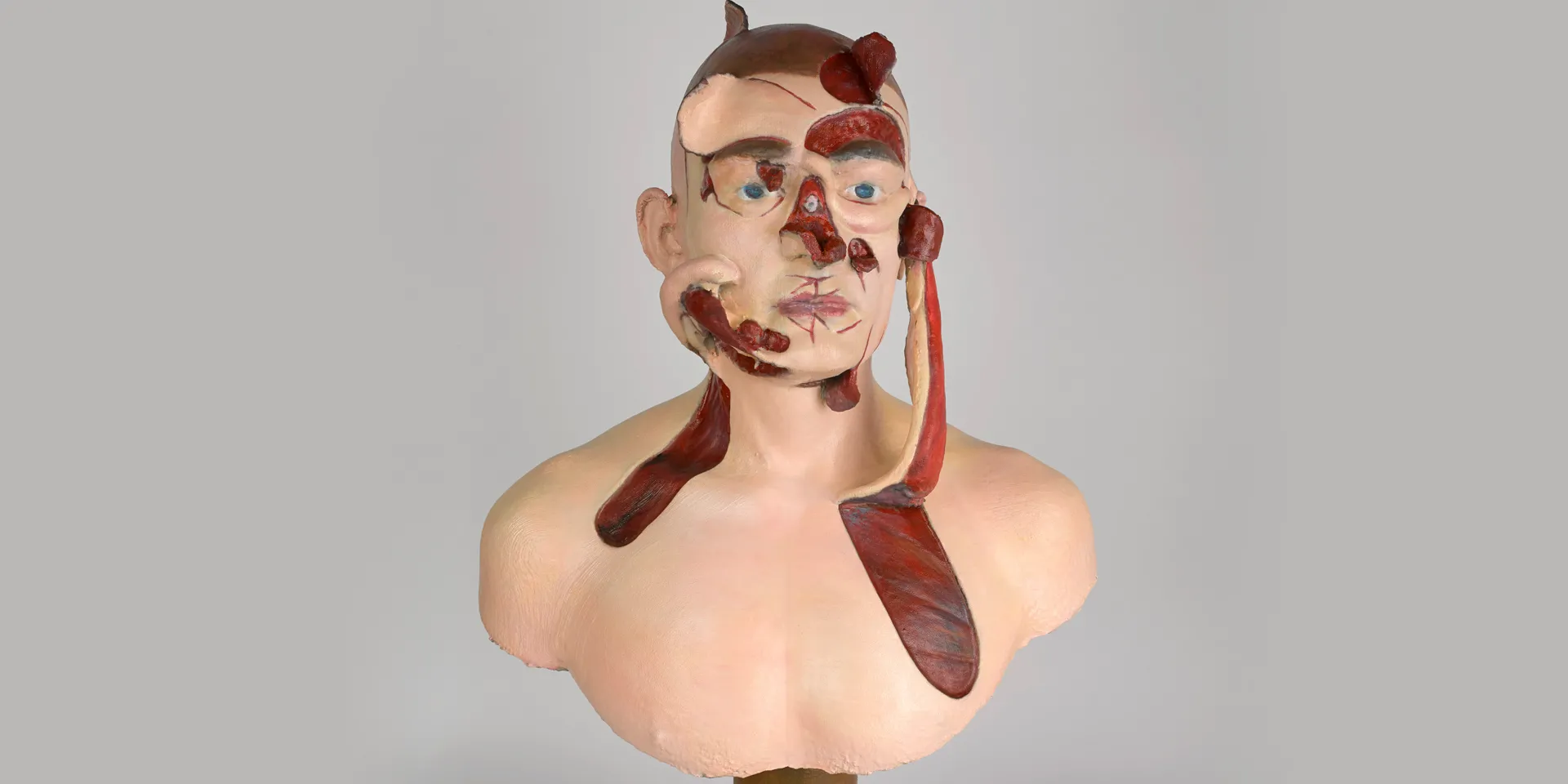

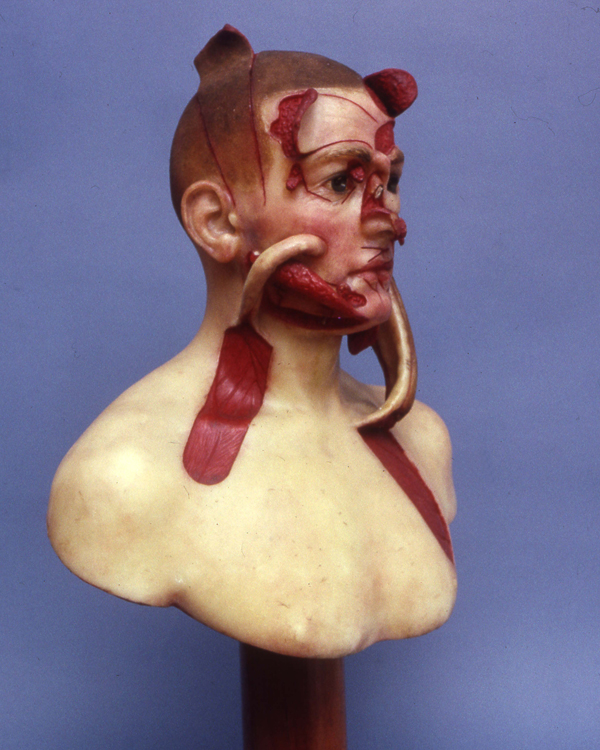

The New Zealand Medical Corps facial and jaw injury unit, led by Henry Pickerill, transferred to Sidcup in 1918. Pickerill himself treated over 200 men and became a renowned plastic surgeon. He developed teaching models, casts and busts to demonstrate the rapidly changing methods of facial reconstructive surgery.

Original wax teaching model, 1917

3D printed copy of teaching model, 2016

The National Army Museum holds a 3D printed copy of Pickerill's wax teaching model in its collection. The original belongs to the Royal College of Surgeons’ Hunterian Museum.

Like Pickerill, the Museum hopes to use the model to share knowledge about the birth of plastic surgery.

Outcomes

Thousands of men suffered long-term disabilities as a result of the First World War. Improvements in plastic surgery and facial reconstruction techniques brought some relief. But many were left to fend for themselves with little financial or social support from the state.

Gillies recognised that the disfigured men he treated would be disadvantaged in the job market. So he introduced training schemes to give the men interests and new skills.

His patients responded to their injuries in different ways. Many went home, grateful for and happy with the work done for them. But some men never left The Queen's Hospital, unwilling to present themselves to a curious and sometimes hostile world.

‘We had two night watchmen, both wounded very badly in WW1. They had gone through facial reconstructive procedures after the War but the price they paid for their Country was unbelievable. They were so disfigured, only night work was possible, they never looked us in the face, but we (the nurses) began to feel comfortable with them, feed them a sandwich and a cup of tea on a cold night... Stan the one I knew best told me he had never had a family, never been to a dance, never enjoyed a girlfriend even before the war.’Nurse at Queen Mary's Hospital Sidcup — 1950s

Legacy

Today, Gillies is often referred to as the 'father of plastic surgery'. Many of the techniques he developed during the First World War are still used in modern reconstructive surgeries.

The concept of cosmetic surgery also emerged as a result of Gillies’ work. His desire to restore normal appearance, as well as functionality, was revolutionary. For the first time, patients could choose the nose or jaw their doctors would build for them.

Even so, the surgery Gillies' patients received was born of necessity. Their situation was a far cry from the purely cosmetic face lifts and nose jobs we see today.