Men of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers on duty during house-to-house visitations, Bombay, 1897

Support

The Army’s role in supporting civilian authorities during health emergencies has recently been brought into focus by the Covid-19 crisis. However, this is by no means the first time that soldiers have been called upon to help combat disease.

The Museum holds a photographic collection documenting the Army’s work fighting a bubonic plague epidemic in the Indian city of Bombay (Mumbai) in 1896-97. As with Covid-19, this effort was shaped by debates about its impact upon the economy and the civilian population.

Plague

Bubonic plague has ravaged the world for centuries. The most notorious outbreak was the ‘Black Death’ of the 14th century, which wiped out around half the population of Europe.

Its arrival in Bombay in the summer of 1896 was part of a deadly pandemic that had originated in China in the 1850s and continued to afflict many parts of the globe until the 1950s.

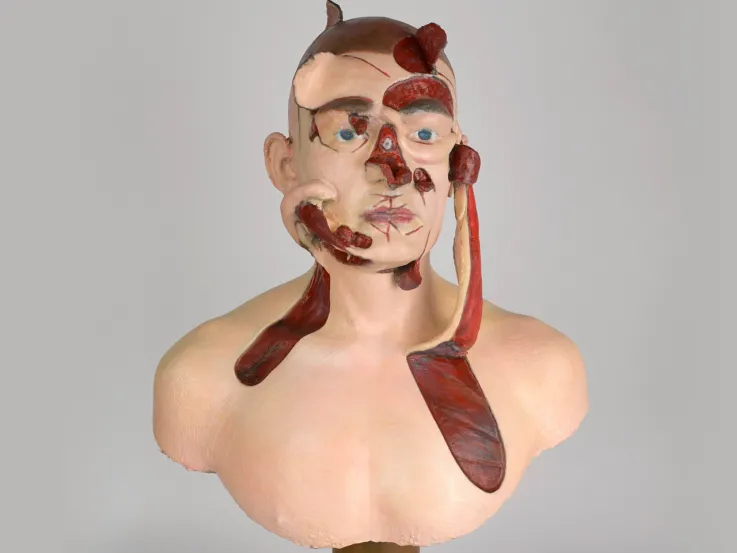

The symptoms of bubonic plague are horrific, including high fever and glandular swellings or 'buboes', most often in the groin and armpits. Until the advent of modern antibiotics, death usually followed within days. Only a small percentage of victims survived.

Outbreak

Known as ‘The Gateway to India’, Bombay was one of the most important ports and commercial centres in British India. By 1896, it was a city of over 800,000 people.

The plague probably arrived there in early August and the first cases were diagnosed the following month. However, the authorities’ response was hampered by their inexperience of dealing with the disease.

They were also reluctant to admit the extent of the problem, knowing the severe impact it would have on trade, most significantly though the imposition of quarantine measures imposed on ships sailing from the port.

However, the gravity of the situation could not be played down for long. By October, a municipal plague committee was in place, led by officers of the Indian Medical Service (IMS), part of the Indian Army.

Indian Medical Service

The IMS had been established in 1763 by the East India Company, the commercial organisation which had founded Britain’s empire in India.

Following the Company’s administrative model, the IMS had originally taken the form of three services, one for each of the regional Presidencies: Bombay, Madras and Bengal. In line with wider Army reforms, these were amalgamated into a single service in 1896, just prior to the plague’s outbreak.

The primary responsibility of the IMS was maintaining the health of the Indian Army. However, its officers also took on important civil functions. This was reflected in its formal division into civil and military branches in 1858. In their civil capacity, IMS officers often took up important state and municipal public health positions.

Burning a suspected plague patient's clothes, Bombay, 1896

Disaster

The municipal committee instigated a policy of isolating plague victims, disinfecting or destroying infected dwellings, and inspecting travellers. However, these measures not only failed to stem the spread of the disease, but also proved unpopular and exacerbated the mass exodus from the city which had been caused by the outbreak.

By March 1897, hundreds of thousands of people had fled and the plague’s death toll stood at around 20,000. It had also begun to spread inland and would eventually afflict many parts of the country.

Differing views

The authorities' initial response revealed how their concern to protect lives was compromised by a desire to preserve Bombay’s place as an important trading hub. Yet their actions were also mediated by a debate over how the situation should be handled.

At the highest levels of government, this was borne out in a dispute between Lord George Francis Hamilton, the Secretary of State for India, who pushed for stringent measures in the hope that they would swiftly stamp out the disease, and the Viceroy, Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin, who advocated a more cautious approach.

Elgin, along with many other Indian officials, was mindful of the lessons of the Indian Mutiny (1857-59). He was reluctant to implement measures which would impinge upon the rights and customs of the Indian people and possibly provoke civil unrest.

'The critical state of affairs was not due to the shortcomings of the city’s authorities, but to the unreadiness of the inhabitants, their great dislike and distrust of sanitary measures, and their fear of being separated from their families.’Lord Sandhurst, Governor of Bombay, to Lord Hamilton, Secretary of State for India — January 1897

A new approach

Despite the reservations of those who advised caution, it was the more draconian approach which was put into action in the spring of 1897. This was underpinned by a new piece of legislation, the Epidemic Diseases Act, which gave the government wide-ranging powers to tackle the problem.

New plague committees were set up in the affected areas to implement this tougher policy. In Bombay, the municipal committee was replaced by one of a more overtly military character, headed by Brigadier General William Gatacre of the Indian Army.

Search and segregate

The isolating of plague patients and disinfecting of streets and houses was implemented on a grander scale. This involved rigorous searches of infected areas, with search parties empowered to enter any suspect houses. The disinfection process included the use of powerful pumping engines to hose down buildings with chemical disinfectants.

Travellers were also more rigorously inspected and those thought to be infected were detained. This was part of a wider policy of segregating all people who had come into contact with plague victims. To facilitate these measures, a number of special hospitals and camps were set up around the city.

Army roles

British Army units, and their Indian Army counterparts, were widely employed in this effort. Soldiers were used to cordon off areas, assist search parties, enforce travel restrictions, guard camps and supervise the disinfection process.

Their work was captured on camera by Captain C Moss of The Gloucestershire Regiment. His photographs were compiled into the album displayed here, entitled 'Plague Visitation, Bombay, 1896-97'.

'We treated houses practically as if they were on fire, discharging into them from steam engines and flushing pumps quantities of water charged with disinfectants.'British public health official, Bombay — 1897

Medical knowledge

Despite this vigorous and systematic approach, the authorities’ efforts were severely undermined by a lack of knowledge about the disease.

Great advances had been made in this period. The plague bacilli had been identified two years earlier. And in January 1897, Dr Waldemar Haffkine of the Bombay Plague Research Committee had succeeded in developing a promising vaccine.

Unfortunately, the role of rats and fleas in the transmission of the disease was not fully understood. This initially rendered the containment methods largely ineffective.

Backlash

Moreover, as Elgin and others had feared, such stringent measures were widely viewed by the Indian people as excessive and as an infringement on their rights and customs.

Movement restrictions interfered with religious pilgrimages and compulsory house inspection was resented as a violation of privacy. Enforced segregation in camps and hospitals was also widely disliked.

Opposition and unrest began to grow. When riots and strikes broke out in March 1898, the authorities were compelled to change tack. The military search parties were withdrawn, and a system was introduced based on co-operating with local people.

Cost

From 1898, efforts to combat the disease were greatly aided by a growing awareness of how it was spread. This notably led to a large-scale programme of rat elimination. Slum-clearance schemes and the extensive use of a new vaccine also made a significant contribution.

However, the plague still took a terrible toll. It spread to many other areas, with the Punjab being particularly badly affected. It was only in the early 1920s that it finally began to abate, by which time it had caused the deaths of at least 10 million people in British India.