Line of duty

Alfred Lionel Smith was born in St Albans, Hertfordshire, in 1894. He served with the Royal Field Artillery during some of the earliest engagements of the First World War (1914-18), arriving in France with the British Expeditionary Force on 19 August 1914.

After taking part in the Battle of Mons (23 August), he was reported to have been killed in action at Le Cateau (26 August).

Alfred’s parents, George and Caroline, were duly informed of their son's death. A local newspaper published his obituary, declaring him the first St Albans man to be killed in the war. Caroline died the following year, still mourning the tragic loss of her son.

But this soldier's story has a twist. Alfred wasn't dead.

‘One Sunday afternoon, my brother-in-law told me he’d been clearing out his late father’s loft and had found some things he thought the Museum might want... I have to admit, my heart sank a little. Whilst every campaign medal has immeasurable value to the person who earned it, and by extension their loved ones, the Museum already has plenty of these First World War medals in the collection... But then he began to tell me his grandfather’s story.’Kate Swann, Senior Curator, National Army Museum — 2024

Man alive

Alfred had indeed been shot during the Battle of Le Cateau, first in the ankle and then in the back. But he later regained consciousness and found himself on a train bound for a prisoner-of-war camp in Germany.

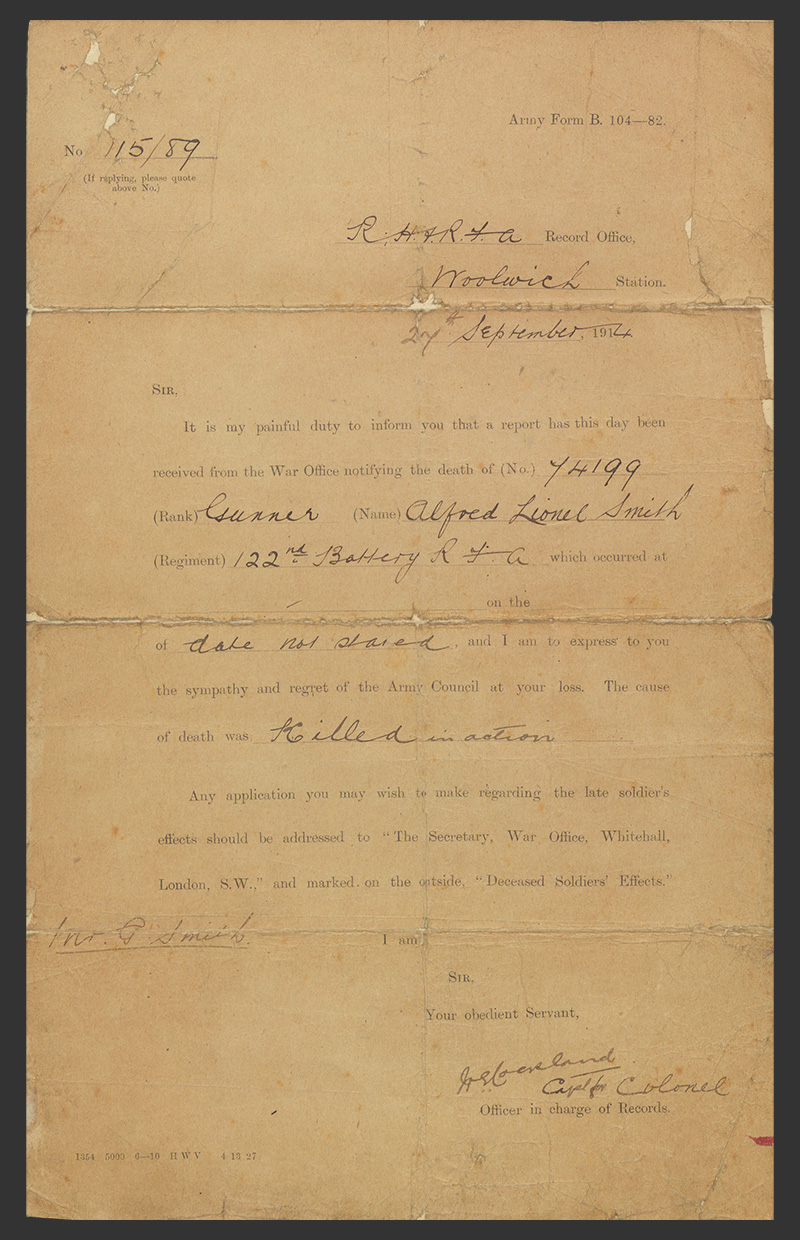

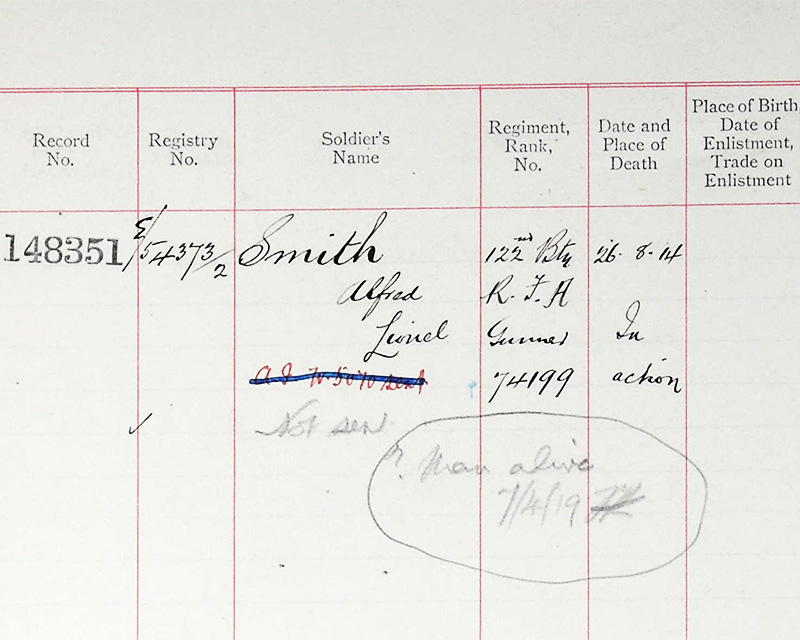

It remains unclear how or why the War Office reported Alfred as dead. The error was not discovered for some time. The official Soldiers' Effects Records held by the National Army Museum mention that his death happened 'in action', but they don't say where he died. The correction ‘Man alive’ is scribbled in pencil underneath, dated 7 April 1919.

Details of Gunner Smith's reported death, Soldiers' Effects Records, 1901-29

Release from captivity

Alfred remained a prisoner of war (POW) for the rest of the conflict. He received no proper treatment for his wounds and was put to work alongside the other inmates. He managed to escape three times but was always recaptured. He was later sent to a different camp on the Russian border, where conditions were even harder.

By the time of Alfred’s release at the end of the war, George Smith had been informed that his son was in fact alive. Even so, he collapsed at the shock of seeing him again for the first time.

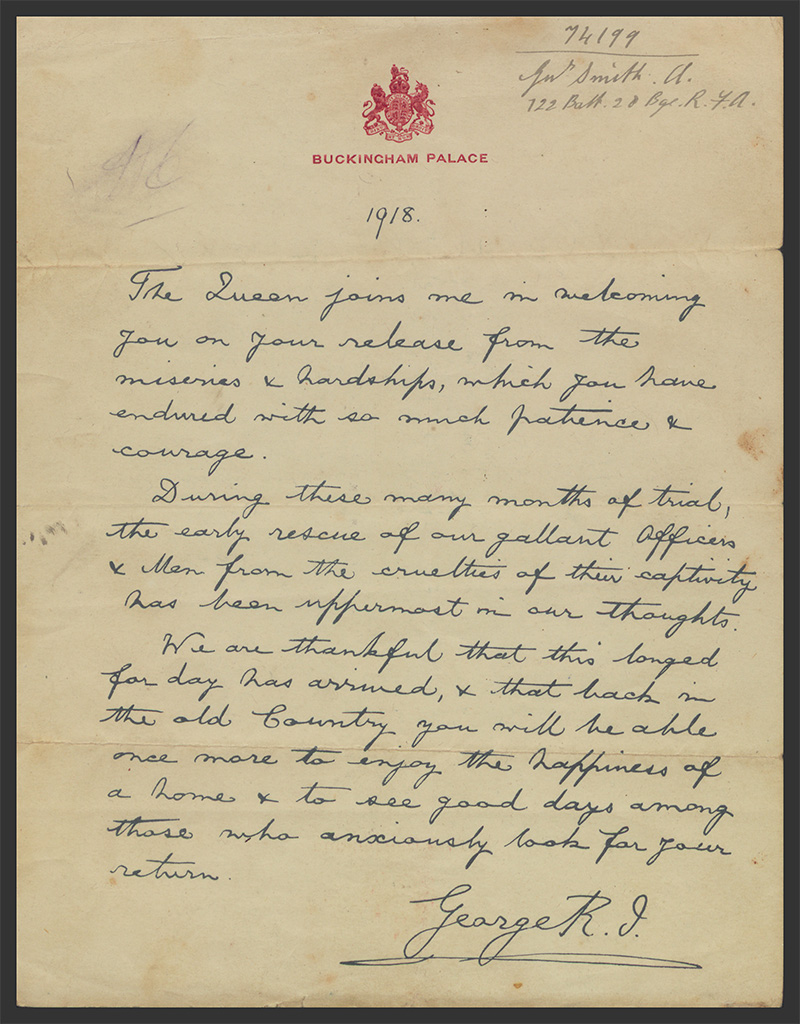

In 1918, Alfred received a printed letter of appreciation from King George V and Queen Mary. This letter, sent to all freed POWs, welcomed his ‘release from the miseries and hardships, which you have endured with so much patience and courage’.

In memory

Despite Alfred’s safe return and gradual assimilation back into civilian life in Hertfordshire, his name still ended up on the War Memorial in St Albans city centre, which was unveiled years later in May 1921.

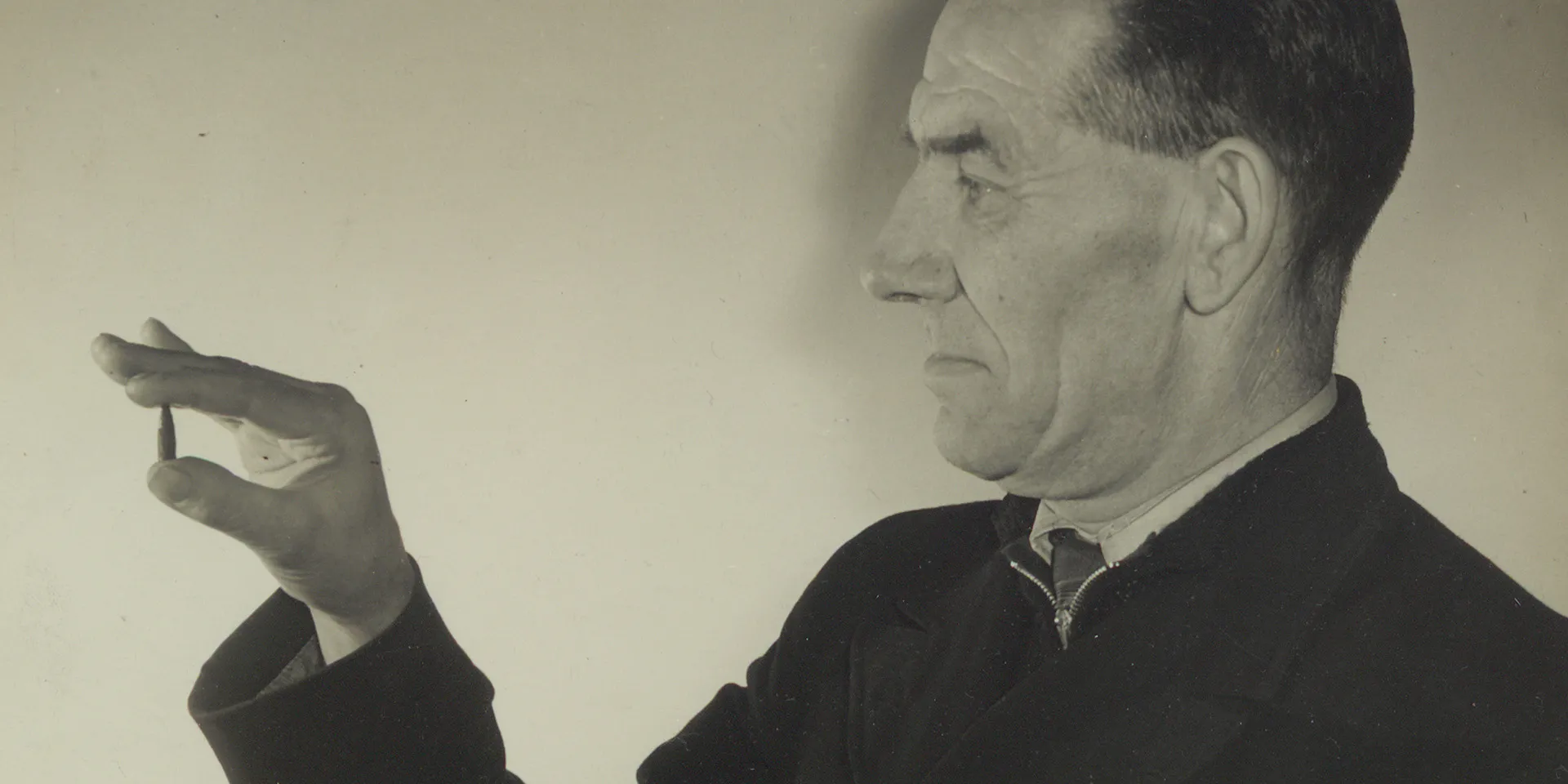

Local news articles from the 1950s and 1960s ran stories with photographs of Alfred pointing to his name in apparent bemusement. It remains there to this day.

Surprise discovery

But Alfred’s strange story doesn’t end there. Twenty-six years after being shot in France, he collapsed one day while walking down the street. Initially, doctors told him it was bronchitis, but an X-ray revealed that he had been carrying a bullet in his left lung ever since the war.

It was successfully removed in a pioneering operation reportedly watched by surgeons from around the world. He even got to keep the macabre memento. He lived to the age of 73, passing away after an eventful life in 1967.

‘As a museum curator, my job is to bring the stories of people and places to life through objects. So, in some ways, Alfred’s own words when he looked at his name on the St Albans War Memorial sound rather prophetic: “He’s not dead, he’s right here.”’Kate Swann, Senior Curator, National Army Museum — 2024

See it on display

You can find the bullet retrieved from Alfred’s lung in our Soldier gallery, alongside his First World War medals and the Army form that mistakenly announced his death.

These exhibits are displayed with a range of other items examining the physical and mental impact of military combat.