BEF arrives

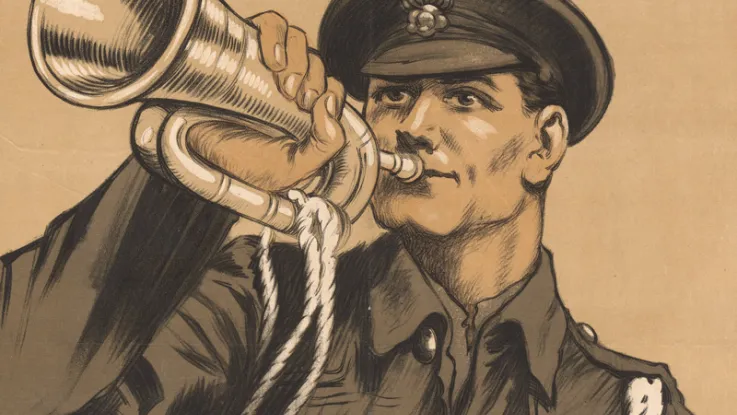

Following the outbreak of war, Field Marshal Sir John French’s British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was sent across the Channel to support France. These were well-trained and experienced soldiers.

Comprising only four (later reinforced to six) infantry and one cavalry divisions - some 90,000 men - the BEF was tiny compared with the German and French armies.

‘It is my Imperial command that you concentrate your energies… upon one single purpose, and that is that you address all your skill and all the valour of my soldiers to exterminate the treacherous English and walk over General French's contemptible little army.’Kaiser Wilhelm II — 19 August 1914

Mons

On arrival, it was sent to a concentration area on the left of the French Fifth Army near Maubeuge on the Belgian frontier. This placed the BEF squarely in the path of the German First Army as it advanced through Belgium.

On 22 August 1914, warned of the German advance by cavalry patrols, the BEF took up a defensive position along the Mons-Condee canal. The following day, the Germans blundered into them. They were stopped by accurate British rifle fire and suffered heavy casualties.

Retreat

Despite the success at Mons, the BEF’s right flank was exposed by the withdrawal of the French Fifth Army and it too was forced to fall back. On 25 August, the French Commander, General Joseph Joffre, ordered a withdrawal to the River Marne.

Map of the retreat from Mons to the Marne, 1914

During the next 10 days, the BEF carried out a 200-mile (320km) fighting retreat in hot weather. The BEF suffered thousands of casualties in a series of holding actions at Landrecies (25 August), Le Cateau (26 August), Étreux (27 August), Cerizy (28 August), Néry (1 September), Crepy (1 September) and Villers-Cotterêts (1 September).

French overruled

At this point, Field Marshal French seems to have suffered a temporary loss of nerve. He decided that his troops needed to be pulled out of the line for a rest.

Aware of the impact that this would have on Anglo-French relations, Field Marshal Earl Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, intervened in person and overruled him. On 3 September the BEF withdrew across the Marne.

BEF counter-attacks

Believing that the French Fifth Army and the BEF were now beaten, the Germans decided to wheel east rather than west of Paris. This exposed their flank to a counter-attack on 5 September. The BEF marched into the gap between the German First and Second Armies and in the following week helped drive them back to the River Aisne.

The Germans dug in on the high ground of the Chemin des Dames ridge on the north bank of the Aisne. In mid-September, they defeated a number of attempts to dislodge them. The Allies then attempted to outflank the Germans to the north.

Race to the sea

This set in motion a period of fighting from late September to the end of November 1914 that is often called the ‘Race to the Sea’. Both sides attempted to outflank each other, gradually moving northwards towards the French-Belgian coast.

‘As soon as it became light, the storm broke. The trenches, lane, and village were deluged with shells of all calibres. It was impossible to move and many men were hit… About 25 men attempted to run, but not a single man got more than half way and they seemed to me to be killed outright.’Captain Hubert Rees describing the German attack at Gheluvelt near Ypres — 1914

First Battle of Ypres

In October 1914, the BEF, now reinforced to twice its original size with Indian and Territorial divisions, was switched from the Aisne to Ypres in Belgium.

From 20 October to 22 November, it helped defeat a major German attempt to break through to the Channel ports. But the cost was high. By the end of the year, it had suffered over 90,000 casualties and the original force had been almost wiped out.

Digging in

The Allied victory at Ypres marked the end of open warfare. Both sides dug in and a line of trenches 466 miles (750km) in length soon ran from the Channel to the Swiss frontier.

The Germans had captured large parts of northern France and Belgium. They built defences in order to hold this ground, hoping to bargain with it when peace came. As a result, their trenches were substantial from the start.

The British and French always viewed trenches as temporary measures. Digging in deep risked sapping morale. Trenches would only be needed until the next ‘Big Push’: the attack that would bring the return of mobile warfare and the liberation of France and Belgium.