Uprising

The Mediterranean island of Cyprus had been under British administration of one form or another since 1878, becoming a Crown colony in 1925.

In the early 1950s, rising nationalism led the majority Greek-Cypriot population to demand 'enosis', or union with Greece. But the British, who were planning to transfer their Suez military headquarters to Cyprus, ruled this out in 1954.

In response, the National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA), under the leadership of Colonel George Grivas, began a guerrilla campaign aimed at forcing the British out.

Emergency

In 1955, Grivas organised anti-British riots. When EOKA then launched a series of terrorist attacks, the governor of Cyprus, Sir John Harding, declared a state of emergency.

Following the example of Malaya, Harding tried to co-ordinate the activities of the civil, military and police authorities, with the specific aim of collecting and processing intelligence.

EOKA

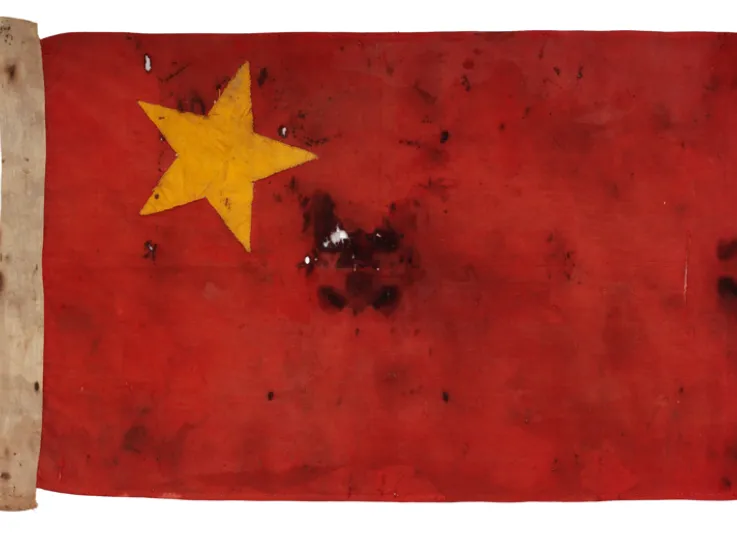

At its peak, EOKA probably numbered around 1,250 members. They were poorly armed, relying on smuggled or stolen weapons and even homemade firearms.

Its fighters had no access to larger weapons, like mortars, and simply made their own. The mortar pictured below is a simple metal tube, which fired a homemade bomb full of scrap iron.

‘I thought we were there to keep the peace. That’s what I thought we were there for but… you just do not know who the enemy is, and this makes it so damned hard. It makes you so mistrusting of everything and everybody that moves. And I think you live in a sort of void for that period that you’re out there, because you try to become alert all the time. You don’t allow yourself to relax. And I think that is really the hardest thing’.Private Pat Baker, Cyprus — 1957

Policing problems

Grivas enjoyed the support of the majority of the Greek-Cypriot population. This made it almost impossible for the British to obtain intelligence about EOKA and its activities.

EOKA also began a campaign of intimidation against Greek-Cypriot members of the police force. As a result, the British were forced to rely on Turkish-Cypriot policemen, who were ostracised by the Greek-Cypriot communities and could provide little information about them.

EOKA evasive

By mid-1956, there were 17,000 British servicemen in Cyprus. However, the operations they mounted against EOKA were not particularly effective. For example, a major operation in the Troodos Mountains in June 1956 only netted a handful of EOKA members.

EOKA kept up the pressure on Britain by extending their campaign to the towns of Cyprus, where they attacked British servicemen and their families. The British response was also hampered by the need to commit troops to an Anglo-French operation in the Suez Canal Zone in Egypt.

Diplomacy wins

The British enjoyed a little more success when the garrison on Cyprus was reinforced with troops from Egypt. Grivas was forced into hiding and two other EOKA leaders, Markos Drakos and Grigoris Afxentiou, were killed in January 1957. Their gangs were soon broken up. Eventually, diplomatic efforts delivered a compromise.

The Greek-Cypriots abandoned their demands for 'enosis' and Cyprus became an independent republic in 1960. Meanwhile, Britain retained control of two Sovereign Base Areas, at Akrotiri and Dhekelia.

Map of Cyprus, 1963

Peacekeeping

By December 1963, relations between the majority Greek-Cypriot and the minority Turkish-Cypriot communities had deteriorated. There were armed clashes between the two sides, particularly in Nicosia.

Forces from Greece, Turkey and Britain were deployed to keep the peace and a ‘Green Line’ was established to keep the two sides apart.

United Nations

In March 1964, United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) replaced the existing peacekeepers. Their mandate was to prevent a recurrence of fighting, maintain law and order, and promote a return to normality.

Soldiers were drawn from a number of nations. Britain contributed a battalion of infantry, a reconnaissance squadron, and helicopter flight plus support services.

Coup and invasion

In July 1974, Greek-Cypriot extremists, backed by the Greek military junta, staged a coup in Cyprus. Once again, their demand was 'enosis'.

This sparked a Turkish invasion, which overran about 40 per cent of the island. The Greek-Cypriot National Guard responded by attacking Turkish-Cypriot enclaves.

UNFICYP was powerless to stop the invasion, but it managed to evacuate foreign nationals and arranged local ceasefires. Reinforced by British troops from Dhekelia, UNFICYP also stopped the Turks from seizing the airport at Nicosia.

Cyprus divided

Cyprus now became, in effect, two separate states, with UNFICYP policing the 180km (112-mile) buffer zone between them. And that's the situation that still exists today.

As of 2017, approximately 270 British soldiers serve with UNFICYP on six-month tours. The British oversee Sector 2, which covers the capital Nicosia. It is traditionally the most volatile area, with frequent demonstrations.

Sovereign bases

Covering 98 square miles (157km), the sovereign bases enable Britain to maintain a permanent military presence in the eastern Mediterranean. RAF Akrotiri is an important staging post for military aircraft and also offers communication facilities. The bases have been used for a variety of military and humanitarian operations.

The Army’s presence in Cyprus includes two infantry battalions, a Joint Service Signals Unit, a Squadron of Royal Engineers, a unit of the Royal Military Police and an Army Air Corps helicopter flight.