Background

National Service was introduced in 1947 to overcome challenges and resolve military manpower shortages in the wake of the Second World War (1939-45).

Wartime conscription was extended into an obligatory period of National Service for men of military age. More than 2 million were called up to the armed forces, often serving in one of Britain’s many garrisons around the world.

Basic training

After attending a medical and joining up, all conscripts had six weeks of basic training during which they got used to military life.

Once enlisted and inside camp, National Servicemen were issued with their equipment, uniform (which often didn't fit) and boots. Conscripts were knocked into shape by sergeants under pressure to train them in as short a time as possible.

Recruits soon began the seemingly endless polishing of kit and equipment. Many regarded this as mindless drill aimed at destroying individuality. However, this strict regime helped foster a group identity and brought recruits closer together.

‘My battle dress blouse fitted me perfectly so the quarter-master sergeant apologised and assured me it didn’t usually happen.’Private Gordon Kell, Royal Army Medical Corps — 1952-54

Specialisation

Officers who did four years or more on a Short Service Commission were allowed to train in a speciality. Many other ranks were trained in general clerical duties, such as typing.

Some received more specific training in technical subjects, such as communications and engineering. Languages could also be learnt - especially Russian in the Cold War period - at the Joint Service School of Languages at Bodmin.

‘Endless drill, gruelling inspections, physical training, rifle practice, polishing boots and equipment, cross country runs, lectures in the art of warfare, fatigues of all sorts and all the time corporals and sergeants continually shouting and swearing from morning till night.’Lance Corporal Adrian Cooper, Royal Engineers — 1947-49

Accommodation

Most conscripts lived in cold barracks with primitive toilets and poor washing facilities. Some were lucky, and had newly built brick barracks with central heating.

Some were housed in a ‘Barrack Spider’ - a wooden hut with eight rooms and a washing area. Twenty men were housed in each room. Each man had a steel wardrobe, an iron bed, and a one-foot locker for small items of kit. The Army’s Officer Training School at Eaton Hall had better quality rooms and baths.

Overseas accommodation varied a lot. Servicemen could find themselves sharing a tent with three other men, such as in camps in Cyprus, or even as many as 15, as in Korea.

The camps and accommodation for servicemen in the Suez Canal Zone were poor, but those in Germany were generally of a high standard. Mosquito nets were necessary in Malaya and Korea.

Pay

Basic pay for a private soldier was 28 shillings (£1.40) a week in 1948. This compared poorly with the average weekly wage in 1951, which was eight pounds, eight shillings and six pence. Those on a Short Service Commission would get extra pay.

Pay for conscripts rose to 38 shillings in 1960. However, the average weekly wage for men in 1961 was 15 pounds, 10 shillings.

Sometimes the low wages were reduced by deductions for lost or damaged kit and equipment. National Servicemen often had little money left for social activities beyond a visit to the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI).

New dangers

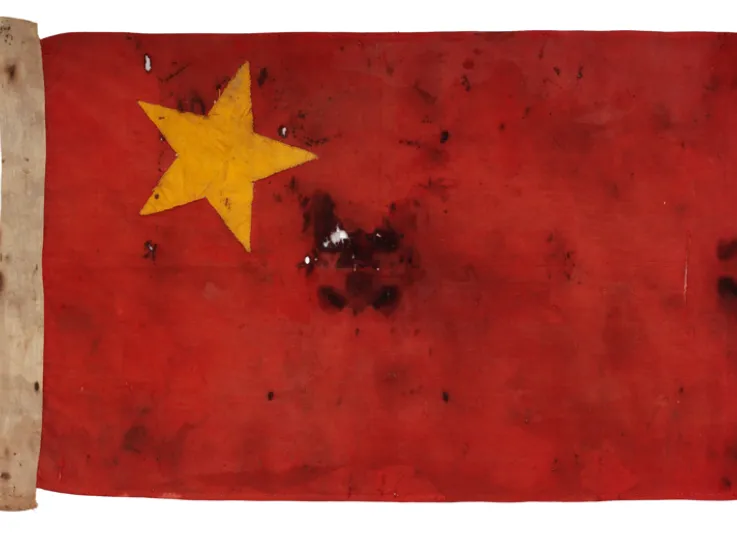

For those deployed to a war zone, the risk of death became part of daily life.

For many, the experience of being thrown into combat situations - such as in Korea, Malaya and Suez - would never be forgotten. Men with minimal training were suddenly expected to fight guerrillas, or cope with riots or civil war situations.

Between 1947 and 1963, a total of 395 National Servicemen were killed on active service.

‘So I looked and all his side was out and he was dead. He’d been in the Army only a few months. He was a new draft... I just can’t pinpoint how I felt, but I know I was shi*ting myself, I was frightened.’Private Eric Pearson, Lancashire Fusiliers — 1948-50

Demobilisation

A National Serviceman’s time in the Army ended when he was discharged, or ‘demobbed’, back to civilian life.

Soldiers greeted demob with mixed feelings. Some had lost friends in action. Many would miss the camaraderie and time abroad. A few would choose to stay on as regular soldiers.

But most were impatient to escape the monotony of training and the dangers of life on the front line.

‘I made comrades the like of which I have never done ever again. I looked forward to demob for two years but when the day came, “Christ, hey, I’m going to miss you guys.”’Private Trevor Baylis, Royal Sussex Regiment — 1959-61

The best and worst of times

National Service was a shock to the system for many. But others relished the opportunities and experiences it gave them.

Bonds formed quickly between men from disparate backgrounds, thrown together in strange situations. These bonds were strengthened by the discipline imposed on them from basic training onwards.

Some of the friendships formed during National Service would last a lifetime.

‘Private Sullivan said to me while we waited... “Jim,” he said, “When people ask you what National Service was like, don’t forget to tell them it was awful. It was f**kin’ awful,” he said. I have never forgotten that chap’s words.’Private Jim Vinall, Royal Army Pay Corps — 1958-60