The route east

Britain's interest in the Mediterranean Sea and the Middle East emerged primarily from its strategic relation to possessions in Asia, most significantly India.

Egypt was of particular importance as it provided the shortest route to the riches of the east. Described as 'the master-key to all the trading nations of the earth', it became a theatre of battle during the Wars of the French Revolution (1792-1802). This was a series of conflicts that pitted post-revolutionary France against Britain, Prussia, Russia, Austria and other European monarchies.

During the 16th century, the Ottomans had absorbed Egypt into their empire, retaining the local Mamluks as the ruling class. By the 1790s, the Mamluks still ruled Egypt, officially on behalf of the Ottomans, but effectively as a semi-independent state.

‘To destroy England truly, we shall have to capture Egypt.’General Napoleon Bonaparte — 1798

French invasion

In May 1798, the French despatched a force to secure Egypt, strengthen France's Middle Eastern trade and open a possible route of attack towards British India. It was led by General Napoleon Bonaparte.

After capturing Malta en route (12 June), around 40,000 French soldiers landed in Egypt on 1 July. The next day, they took Alexandria before marching on Cairo.

On 21 July, a large Mamluk army attacked Napoleon’s troops at the Battle of the Pyramids. The French deployed in large squares to resist repeated massed cavalry charges and scored a decisive victory. They occupied Cairo the following day.

Nelson’s victory

The British were troubled by the prospect of Egypt becoming a French colony and a potential staging post for an attack on their possessions in India. They decided to send out a fleet under Rear-Admiral Horatio Nelson.

After failing to intercept Napoleon’s expedition at sea, Nelson subsequently destroyed the French fleet at anchor during the Battle of the Nile (1-3 August). This left Napoleon’s army isolated in Egypt. It also encouraged the Mamluks and Ottomans to continue fighting.

Into Syria

After learning that new Ottoman armies were gathering in Syria, Napoleon decided to take the offensive instead of waiting for them to arrive in Egypt. He marched into Syria, winning several victories in February and March 1799, before returning to Egypt due to an outbreak of plague in his army.

On 15 July, an Ottoman force from Rhodes landed from British transport vessels and dug in at Aboukir. Four days later, Napoleon attacked their lines, bringing about an Ottoman surrender on 2 August.

With the French position seemingly secured, Napoleon returned to France, slipping past the British navy in a frigate. He subsequently used his popularity and military support to mount a coup that made him First Consul, the head of France’s government.

Convention

In January 1800, the remaining French troops in Egypt concluded the Convention of El Arish with the Mamluks and the Ottomans. This agreement would have allowed them to leave Egypt and return home unhindered.

When the British refused to accept the Convention, the French attacked the Ottomans at Heliopolis (20 March) and re-captured Cairo.

British landing

The British now sent troops to Egypt under the command of General Sir Ralph Abercromby. Unfortunately, bad weather delayed the landing of his expeditionary force at Aboukir Bay on 8 March 1801, giving the French ample time to organise a response.

Around 2,000 troops from the French garrison of Alexandria, equipped with 10 field guns, positioned themselves along a line of sand dunes overlooking the bay. They inflicted heavy losses on the vanguard of the British force as it disembarked from small boats, each of which carried 50 men ashore.

Despite these setbacks, the British rallied. Led by Major-General Sir John Moore, they charged the defenders with fixed bayonets, securing the beachhead and allowing the remainder of the 17,500-strong army to get ashore with its equipment.

British casualties totalled around 700, while the French sustained close to 400 men killed wounded or captured.

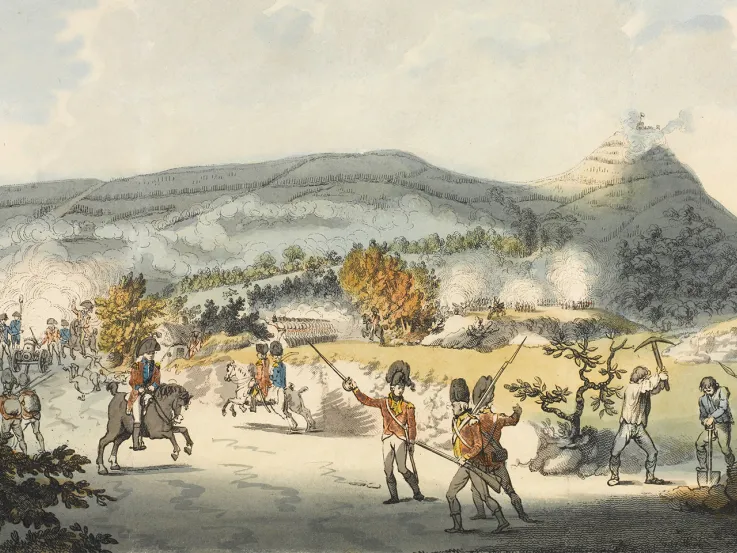

Mandora

Next, the British advanced along the narrow spit of land between the sea and Lake Aboukir. Another stiff engagement ensued at Mandora on 13 March. Around 5,000 French troops manned a strong line of defences, parts of which were eventually breached after close-quarter fighting.

As night fell, the British withdrew to a defensive position five miles from Alexandria, near the ruins of Nicopolis. There, they fortified their position to await a possible French counter-attack.

French casualties during the day’s fighting were around 500 soldiers killed, wounded or captured. British casualties were probably double that.

‘There has seldom been more hard fighting; their numbers were superior to ours, they had the advantage of artillery… but our troops seemed to have no idea of giving way, and there cannot be a more convincing proof of the superiority of our infantry.’Major-General Sir John Moore describing the Battle of Alexandria — 1801

Battle of Alexandria

At dawn on 21 March, the French attempted a surprise attack, under the command of General Jacques-François Menou. The British had expected an assault, but misjudged its timing and direction.

The French proceeded to overrun the British outposts and began attacking their entrenchments in the ruins, primarily the section of line led by Sir John Moore. This included the 28th Regiment, which simultaneously beat off cavalry attacks on both sides of its line.

The customary formation for repelling cavalry was the square. But there was not enough time to form one. Instead, the rear ranks of the line about-turned.

For a while, the whole British line seemed threatened. However, reinforcements and renewed artillery fire - including a bombardment from Royal Navy gun boats which lay close inshore - enabled the British troops to rally and win the day.

The French sustained around 4,500 casualties; British losses were less than half that number. However, among them was General Abercromby, who was struck in the thigh by a musket ball and died of his wounds a week later. Moore said of Abercromby that he was 'the best man, and the best soldier, who has appeared amongst us this war'.

The British victory was a welcome boost to Army morale after setbacks against the French elsewhere.

Cairo and Alexandria

General John Hely-Hutchinson succeeded Abercromby as British commander. He left Major-General Sir Eyre Coote at the head of a 6,000-strong force to keep Menou bottled up in Alexandria, before marching on Cairo.

After a few skirmishes, Hutchinson arrived in the Egyptian capital in mid-June. Reinforced by an Ottoman army, he invested the city, forcing the 13,000-strong French garrison to surrender on 27 June.

On his return from Cairo, Hutchinson encountered fierce opposition at Fort Marabout, which the 54th Regiment eventually stormed. But the French position in Alexandria was increasingly hopeless. They were unable to break out and their food supplies were running low. Memou eventually surrendered his 10,000 troops on 31 August 1801.

Red Sea landing

Meanwhile, a supporting British-Indian expeditionary force had been despatched from Bombay under General Sir David Baird. This landed at Kosseir on the Red Sea on 8 June 1801.

After marching 167 miles across the desert to Qena on the River Nile, Baird's troops advanced another 253 miles to link up with the British force at Cairo. However, by the time it arrived, the fighting was already over.

Aftermath

Most of Memou’s army was eventually repatriated back to France by the Royal Navy. The French also had to hand over to Britain all the Egyptian antiquities they had collected during their campaigning, including the Rosetta Stone.

The French agreement to evacuate Egypt became part of the Peace of Amiens (25 March 1802), which brought the Wars of the French Revolution to an end. Soon after, the Treaty of Paris (25 June) formally concluded hostilities between the French and Ottomans, returning Egypt to the latter.

The Egyptian campaign put paid to France’s aspirations of a Middle Eastern empire. However, Anglo-French fighting would resume the following year.