Explore more from Art and Literature

Drawn on the spot: War artists and the illustrated press

10 minute read

News of the world

During the Crimean War (1854-56) journalists and artists were sent to the battlefield on behalf of newspapers to deliver an unprecedented record of the conflict as it unfolded. War, which had once been a remote event, was suddenly opened up for public scrutiny.

As literacy rates increased and the voting franchise was extended, a wider pool of people began to crave news. As a result, the influence of the press steadily grew. Additionally, new technologies, like the telegraph, fuelled the public's demand for accurate, up-to-date information from around the world.

Improved distribution by railway and cheaper printing methods led to further growth in the newspaper market.

War correspondents

John Delane, the editor of 'The Times', asked the journalist William Howard Russell to accompany the Brigade of Guards when it embarked for Crimea in February 1854. Men like Russell were to be the world’s first genuine war correspondents. They lived and worked on the battlefield to provide a commentary on the conflict's progress.

Their features provided the public with eye-witness accounts from the front line, offering colourful personal perspectives from ordinary soldiers and junior officers, alongside anaemic reports from the government and military commanders.

‘The duty of the journalist is the same as the historian – to seek out truth, above all things, and to present to his readers not such things as statecraft would wish them to know but the truth as near as he can attain it.’John Delane, editor of 'The Times' — 1854

Censorship of the press

Unlike in France, Russia and Turkey, the press in Britain was uncensored. But the British military establishment offered journalists little official recognition, and those in authority regarded them with contempt.

Restrictions on journalists formally materialised in 1856, when Lieutenant-General Sir William Codrington set a precedent for future conflicts by introducing press censorship within the British camp.

Ironically, writing nearly 50 years later, Russell conceded: ‘I am bound to say from my personal experience, that I consider control and supervision of young camp correspondents in wartime to be very necessary in civilised countries.’

‘We regret to learn that Lord Raglan and Marshal de St Arnaud have come to the resolution of preventing, as far as they can, the transmission of news from the seat of the war.’The Illustrated London News — 3 June 1854

Illustrated newspapers

Founded in May 1842, 'The Illustrated London News' was the world’s first illustrated newspaper. Although a number of newspapers had included drawings of news events from time to time, 'The Illustrated London News' was the first to include high-quality wood engravings as a regular feature of its publication.

Its elaborate full-page illustrations were engraved using the end-grain of woodblocks, a technique which had been pioneered in the late 18th century and developed further by a number of magazines in the 1830s.

Unlike steel engraving, the durability of woodblocks meant that they could withstand hundreds of thousands of impressions and could print alongside type.

‘The Illustrated London News', 5 May 1855

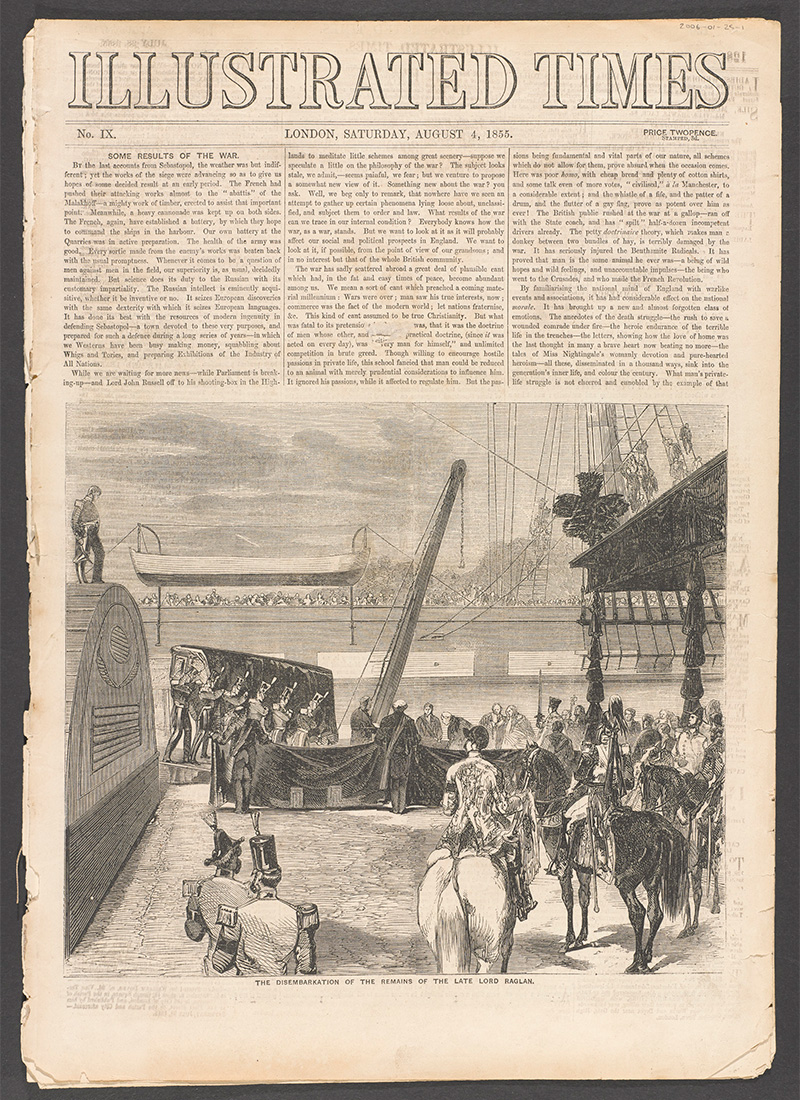

‘Those who possess our volume, possess a reflection of the history of the time, a living picture of all that has happened during it – at once literary and artistic.’Preface to the first issue of 'Illustrated Times', a competitor of 'The Illustrated London News' — established in 1855

Publishing boom

The Crimean War helped 'The Illustrated London News' to double its readership from 100,000 to 200,000 per week. By November 1854, it had become the most popular newspaper in Britain.

But when newspaper duty - known as the ‘tax on knowledge’ - was abolished in 1855, the number of cheap newspapers exploded.

The expansion of the British Empire meant that these illustrated newspapers were also read by soldiers deployed across the globe, eager for news of home and even about the conflicts in which they were fighting.

British newspapers were also of interest to foreign powers. In 1874, copies of 'The Illustrated London News' were found in the palace library of the Ashanti king at Coomassie (now in Ghana).

'Illustrated Times', 1855

From fantasy to reality

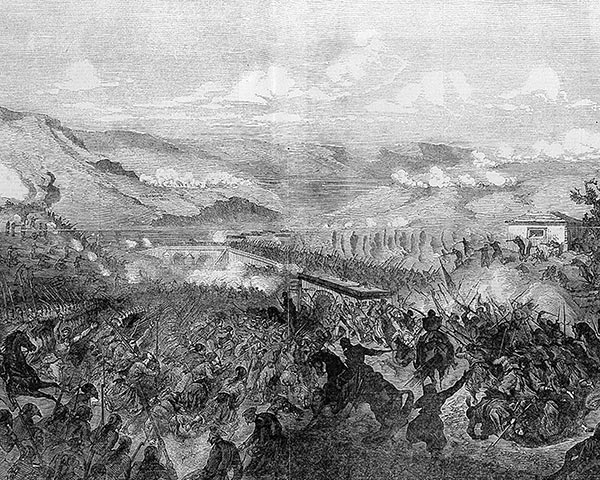

Before the outbreak of the Crimean War, the illustrated press employed artists, such as Gustave Doré, to create images from reports and photographs. Doré’s illustrations were romantic depictions of battles, characterised by dramatic scenes of closely-packed ranks of identical soldiers charging the enemy.

As the war unfolded, imaginary reconstructions of battles no longer satisfied the public's demand for images of war. Drawings like Doré's contrasted with the more realistic images submitted by the special correspondents from the battlefield.

'The Battle of Tchernaya' by Gustav Doré (Published in 'The Illustrated London News', 29 September 1855)

'Town and harbour of Balaklava from the camp of the 93rd Highlanders' by Lieutenant Montagu O'Reilly, 13 November 1854

Military artists

The first illustrations of the Russian naval port of Sevastopol appeared in 'The Illustrated London News' in June 1854. They were produced after drawings by a naval officer, Lieutenant Montagu O’Reilly.

During the course of the war, the illustrated newspapers published many drawings by members of the armed forces. One paper carried advertisements offering the substantial reward of £100 for the best collection of drawings by an officer of the British Army or Royal Navy serving in Crimea showing scenes connected with the war.

Lieutenant Montagu O’Reilly explaining his sketch of Sevastopol to the Sultan (Published in 'The Illustrated London News', 21 October 1854)

‘Our artist on the battlefield of Inkerman’ - Joseph Crowe in the Crimea (Published in 'The Illustrated London News', 3 February 1855)

War illustrators

Initially, 'The Illustrated London News' sent three correspondents to Crimea - Edward Goodall, Joseph Archer Crowe and Constantin Guys - to report as direct observers of the war. Crowe, a talented watercolourist, had been a reporter for 'The Daily News' from 1846.

Artists like Crowe, although employed by the press, were not regarded by the military with the same suspicion as journalists. They were allowed to occupy tents near to those of the Army.

However, living and working so close to the action also had its disadvantages. Crowe’s autobiography is filled with accounts of his encounters with mortars and bullets.

‘Now there was complete light, I could see every shot and shell that came booming along from those sixty guns of “The Mount”. I had to get through the fire, and I watched the shot as they came, and stopped or jumped to dodge them, and this so successfully that I found myself at last on the rising ground near our camp.’Joseph Crowe on the Battle of Inkerman — 5 November 1854

Alterations

Crowe's watercolours were characterised by a vivid fluidity which was lost when they were transferred to print. The dense nature of box-wood - used for wood engraving - meant that it was hard to work, making it difficult to reproduce the subtleties of drawing.

Crowe's sketches were also often revised and redrawn by the engravers in London in order to heighten their sense of drama.

Lieutenant Henry John Wilkinson of the 9th (The East Norfolk) Regiment of Foot was a prolific amateur artist who also illustrated the Crimea War.

His sketches are of variable technical ability and range: from quick, well-observed studies drawn on small sketchbook pages in pencil or pen and ink, to larger, detailed scenes rendered by a delicate use of watercolour over pencil.

'The Illustrated London News' reproduced a number of Wilkinson’s drawings but altered many of them for clarity.

Beyond Crimea

After the Crimean War, printing processes improved so the number of drawn illustrations in the illustrated press declined in favour of photographs. By the outbreak of the Boer War (1899-1902), some illustrated papers used glossy, heavier paper, better suited to reproducing photography.

In March 1900, 'The Illustrated London News' noted that ‘sketches and photographs from South Africa, now arriving in profusion, help those who live at home at ease to picture scenes of which the cable or the newsletter has already made them aware’.

Fought over a vast expanse of territory and far from London, images of the war lagged behind events that they depicted by weeks. But the delay offered some advantages to editors, who could gauge public opinion and publish accordingly. Staff artists could redraw images sent from foreign correspondents to include prominent features or the portraits of prominent individuals.

But the illustrated press included virtually no examples of anti-war or pro-Boer imagery because it was images of heroism that sold newspapers.

William Barns Wollen

After a brief military career with the volunteers, Wollen travelled to South Africa as ‘special artist’ for 'The Sphere'. His oil paintings and magazine illustrations drew on his first-hand observations of battlefields, but as a civilian.

However, he later listed his profession as ‘Army Officer’ in his passport in order to get to France to sketch during the First World War (1914-18).

Objectivity

Wollen was among 150 war correspondents recommended for the Queen’s South Africa Medal for service during the Boer War. While this may imply a loss of objectivity, William Howard Russell had also been awarded campaign medals for his war reporting, and the practice has continued to this day.

During the First World War, the illustrated press was still going strong despite the growing use of photographs. They reported current military news and serialised books, many of which drew on military events of the past.

Richard Caton Woodville

Woodville served in the yeomanry, but saw no action before leaving the Army for a career as a war illustrator. He recreated battle paintings from his imagination, but his attention to the details of uniform made them appear authentic.

Many of his First World War illustrations were reproduced as supplements to illustrated newspapers. These were detailed pictures, often printed in colour on thicker paper in order to promote sales. He focused mainly on dramatic scenes of heroism and sacrifice, which served as good propaganda for the Army.

Children’s publications

The development of comics and children's papers also provided war illustrators with commercial opportunities. With their heroic stories of derring-do, these presented sanitised versions of war, designed to encourage a martial spirit and jingoistic pride.

Some used military history as a colourful background for fictional tales, whereas others identified brave individuals and illustrated real battles. Although most focused on past rather than contemporary campaigns, 'The Boys Illustrated News' and 'The Boys’ Friend' had special correspondents at the front to cater for children’s appetite for war news.

Stanley Wood was a prolific illustrator whose work featured in publications like 'Boy’s Own Paper' and 'Chums'.

‘I went into the TA as a weekend relaxation from drawing… now it seems as if the two sides of my life, the art and the Army, have come together.’Matthew Cook — 2003

A war artist today

While sketches of war are no longer a familiar feature of newspapers, 'The Times' sent Matthew Cook as an artist-reporter to Iraq in 2003. Trained as an illustrator, Cook had also been a Territorial Army soldier for nearly two decades.

Cook’s drawings of Iraq and Afghanistan continue a tradition of military artists capturing the quieter realities behind the mainstream news. They give us a window onto the realities of soldiering, often more subtle and insightful than the photographs that fill modern news reports.