Balance of trade

The First China War (more commonly known as the First Opium War) had its origins in a trade dispute between Britain and Imperial China.

By the start of the 19th century, trade in Chinese goods - such as tea, silks and porcelain - was extremely lucrative for British merchants. However, the Chinese wouldn't take British products in return; they would only sell their goods in exchange for silver. As a result, Britain's silver reserves were being gradually depleted.

To rectify this trade imbalance, the East India Company and other British merchants began to import Indian opium into China illegally, demanding payment in silver. This was then used to buy tea and other goods. By 1839, opium sales to China paid for the entire British tea trade.

Chinese resistance

Opium had long been valued in China as a medicine that could ease pain, assist sleep and reduce stress. By 1840, however, there were millions of addicts across the country, largely sustained by illegal British imports.

The Chinese were keen to put a stop to the imports not only to address these social concerns, but also because they were eroding the trading advantages that China had previously held over Britain.

In May 1839, the Chinese forced the British Chief Superintendent of Trade in China, Charles Elliott, to hand over the stocks of opium at Canton for destruction. This event caused outrage among the British, and was the spark that ignited the war.

Mutual suspicions

Relations between Britain and China were already strained. Shocked by British envoys refusing to kow-tow before the Emperor, the Chinese had refused to enter into full diplomatic relations. Chinese officials remained suspicious of the British and adopted a hostile attitude in negotiations. This was partly the result of cultural misunderstanding.

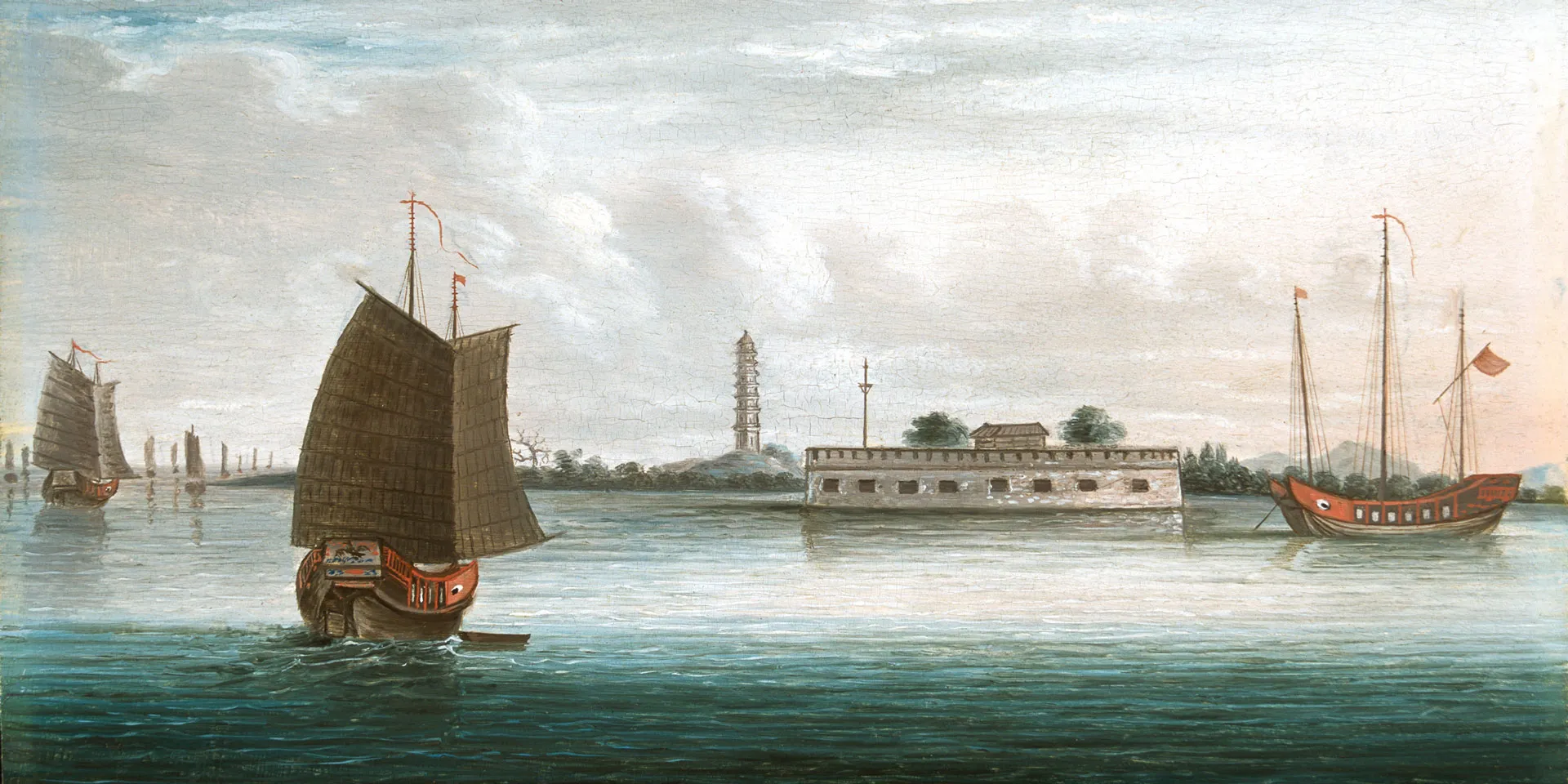

Meanwhile, the British believed the Chinese had always been uncooperative. Since the 18th century, they had only allowed Western merchants to use the port of Canton (Guangzhou). Many British politicians and merchants viewed this dispute as a chance to gain access to trading opportunities elsewhere in China.

Naval engagements

After several skirmishes, fighting began in November 1839. HMS ‘Volage’ and HMS ‘Hyacinth’ defeated 29 Chinese vessels during the evacuation of British refugees from Canton.

On 21 June the following year, a naval force commanded by Commodore Sir Gordon Bremer arrived off Macao, before moving north to the island of Chusan (Zhoushan). On 5 July, it bombarded the port of Ting-hai (Dinghai), which was subsequently occupied by troops under Brigadier-General George Burrell.

Truce

Following this defeat, the admiral of the Chinese fleet, Kuan Ti, asked for a truce. Ten of his 13 war-junks had been captured and his flagship had been destroyed. The force that had captured the forts, commanded by Major JL Pratt of the 26th (Cameronian) Regiment, had suffered only 38 casualties.

In the face of overwhelming British strength, Kuan Ti signed an agreement on 18 January 1841 by which the island of Hong Kong became a British territory.

Failed negotiations

During negotiations, the British foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, demanded that the Chinese pay compensation and cede one of their coastal islands to the British for use as a trading station. When the Chinese refused these demands, hostilities resumed.

On 7 January 1841, the British captured forts on the islands of Chuenpi and Taikoktow that guarded the approaches to Canton at the mouth of the Pearl River.

British demands

Next, the British advanced up the Pearl River with a reinforced military contingent under Lieutenant-General Sir Hugh Gough. They captured Canton on 27 May 1841, then withdrew on the understanding that the Chinese would pay reparations of £60,000.

Charles Elliott, who had negotiated this settlement, was dismissed by Lord Palmerston, who felt he had not extracted enough concessions. Elliott's replacement, Sir Henry Pottinger, imposed additional demands including compensation for the opium confiscated and the costs of the war, the opening of further ports to international trade, and the establishment of diplomatic relations.

Amoy taken

The British moved north again, capturing Amoy (Xiamen) on 26-27 August 1841 and re-possessing Chusan on 1 October. Chinhai (Zhenhai) was taken on 10 October at the cost of three British dead and 16 wounded.

Ningpo (Ningbo) was taken unopposed on 13 October, before operations were suspended for the winter. With negotiations again proving fruitless, the Chinese counter-attacked on 10 March 1842, but were easily repelled.

Assault on Chapu

The British continued moving north, capturing Chapu (Zhapu) on 18 May 1842, in an operation that witnessed brave Chinese resistance. Many Chinese only surrendered after their defences had been breached and their enclosures set on fire by rockets.

During the assault, nine British soldiers and sailors were killed and 55 wounded. One of the dead was Lieutenant-Colonel Nicholas Tomlinson, commander of the 18th (Royal Irish) Regiment.

Victory

Gough and Admiral Sir William Parker then moved on to Shanghai, which was captured on 19 June 1842. Continuing up the Yangtze River, Major-General Lord Saltoun’s 1st Brigade engaged the Chinese at Chinkiang (Zhenjiang) on 21 July. The city was captured and its military commander, Hai-lin, was burned in his house, which had been set alight on his own orders.

British casualties were again modest, totalling 34 dead and 107 wounded. Faced with the possibility of a British assault on Nanking (Nanjing), the Chinese now sued for peace.

Treaty of Nanking

The war ended on 17 August 1842, with the Treaty of Nanking enabling the British to 'carry on their mercantile transactions with whatever persons they please'. The Chinese were compelled to relax their control on foreign trade, including the trade in opium.

Hong Kong was ceded to Britain, and the treaty ports of Canton (Guangzhou), Amoy (Xiamen), Foochow (Fuzhou), Shanghai and Ningpo (Ningbo) were subsequently opened to all traders. The Chinese also paid reparations.

The ease with which the British had defeated the Chinese armies seriously affected the Qing dynasty's prestige. This contributed to the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64). For the victors, the First China War paved the way for the opening up of the Chinese market.