Victory celebrations

Fighting on the Western Front ceased with the Armistice on 11 November 1918, but hostilities with Germany did not end officially until the Treaty of Versailles was signed in June 1919. In Britain, peace was celebrated on 19 July that year, with a Victory Parade in London as the main event.

A camp for the troops taking part was set up in Kensington Gardens and thousands of civilians flocked to the capital for the festivities. Nearly 15,000 British Empire servicemen took part in the parade, led by Allied commanders including Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig and Marshal Ferdinand Foch.

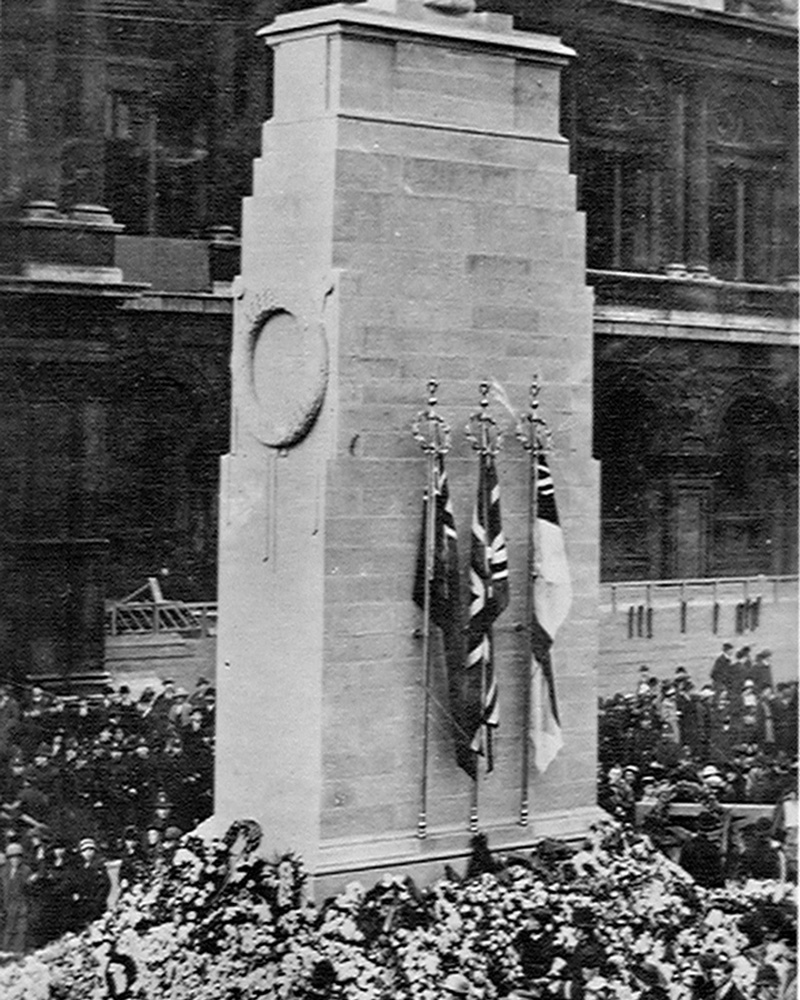

Cenotaph

The architect Sir Edwin Lutyens designed a cenotaph - an 'empty tomb' to honour the dead - for the marching troops to salute as they passed along Whitehall.

His simple and non-denominational monument was represented on the day of the Victory Parade by a temporary structure of wood and plaster. The permanent stone memorial was unveiled on Armistice Day 1920. It is now the scene of the annual National Service of Remembrance.

‘Near the memorial there were moments of silence when the dead seemed very near, when one almost heard the passage of countless wings - were not the fallen gathering in their hosts to receive their comrades' salute and take their share in the triumph they had died to win?’‘The Morning Post’ — 20 July 1919

Criticism

Celebrations and memorial services took place all over the country. But there was some criticism that this was too extravagant when so many ex-servicemen were now unemployed.

In Manchester, demobilised soldiers marched with slogans like ‘Honour the dead - remember the living’, and to demand ‘work not charity’.

Some argued that the money would be better spent supporting returning servicemen who had suffered physical and mental injuries.

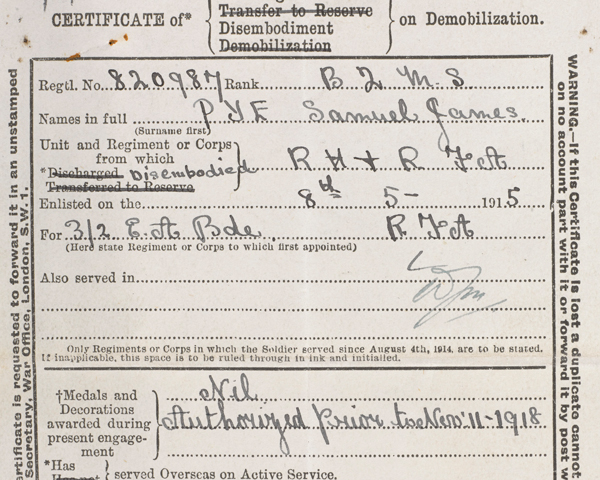

Demobilisation

After the Armistice, steps were taken to demobilise millions of soldiers and repatriate prisoners of war.

The Secretary of State for War, Lord Derby, originally proposed that the first men to be released should be those who held essential jobs in industry. However, as these men were invariably those who had been called up in the latter part of the war, this meant that men with the longest service were the last to be demobilised.

Mutiny

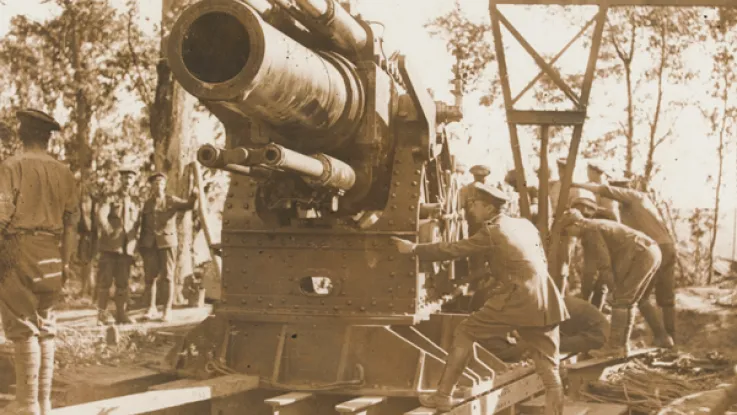

At a time when revolutionary ideas were sweeping across Europe, Lord Derby's scheme was very unpopular. On 9 December 1918, men of the Royal Artillery stationed at Le Havre burnt down several depots in a riot.

On 3 January 1919, frustrated soldiers mutinied at Folkestone when they heard they were being sent back to France. Later that month, a mutiny at Calais involving around 20,000 men witnessed the temporary formation of soldiers’ councils.

Crisis averted

In response, the new Secretary of State for War, Winston Churchill, introduced a new scheme in January 1919.

Based on age, length of service and the number of wounds a man had received, it ensured that the longest-serving soldiers were generally demobilised first.

The new system defused a dangerous political situation, although problems still occurred.

Empire troops

Demobilised Commonwealth soldiers were often left waiting for long periods until transport could be found to ship them home. In March 1919, a mutiny at a Canadian camp in Rhyl was only suppressed after several men were killed.

The men had been living in overcrowded conditions and several had died of flu during the winter. Over 40 rioters were later court-martialled. Twenty-four were tried and convicted of mutiny, but many sentences were later commuted.

On the whole, however, demobilisation was a success.

Quiz

Between 1918 and 1922, by how much did the British Army reduce in size?

In November 1918, the British Army had numbered almost 3.8 million men. A year later, it had been reduced to 900,000. And by 1922, the total was just over 230,000.

Rehabilitation

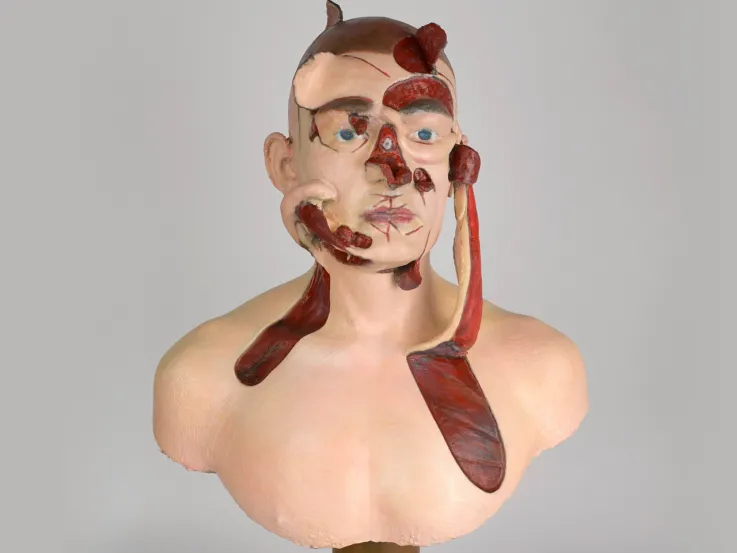

Over 2 million men in the British and Commonwealth armies were wounded during the war. Thousands suffered long-term disabilities caused by amputation, blindness, disfigurement and poison gas damage to heart and lungs.

Others had mental health problems caused by the psychological traumas they had experienced. Improvements in artificial limbs, plastic surgery, facial reconstruction techniques and psychiatry brought some relief. But many were left to fend for themselves with little financial or social support from the state.

Old Comrades

Ex-servicemen’s organisations such as the British Legion (founded in 1921 from Comrades of the Great War and three other organisations) and the British Limbless Ex-Servicemen’s Association (established in 1932) campaigned for better pensions and provided convalescent homes, sheltered workshops, hostels, food and clothing for ex-soldiers and their dependants.

Such organisations, alongside regimental associations, offered many veterans a sense of belonging and a renewal of the comradeship of the trenches.

Fit for heroes?

Despite the Lloyd George government’s promise of a 'land fit for heroes', many ex-soldiers suffered during the 1921 economic slump. Unemployment increased and the ambitious programme of post-war reconstruction was cancelled.

But, despite the widespread industrial and political unrest of the era, the majority of Army veterans were re-integrated successfully into the British economy. Unlike many of their German, Russian and Italian counterparts, most British ex-servicemen did not support extremist political parties or paramilitary organisations.

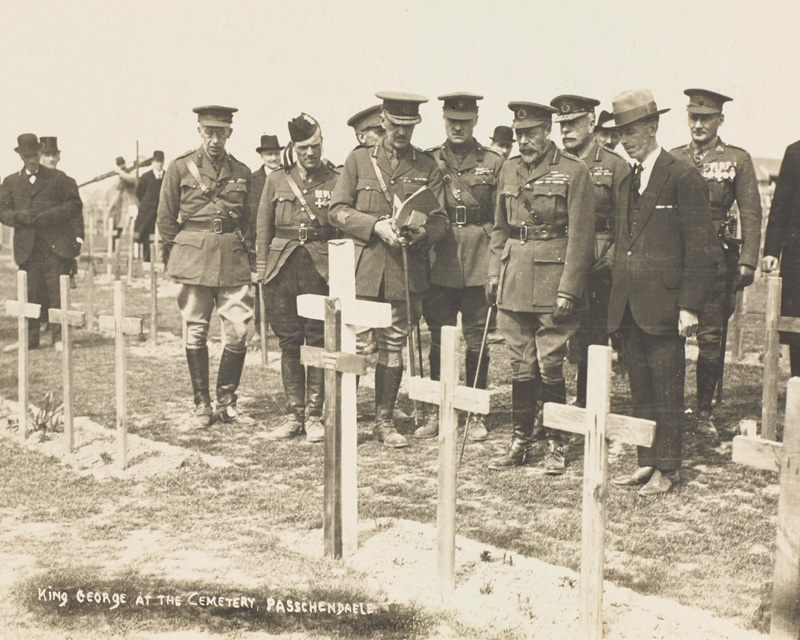

War Graves

Concern for the long-term fate of the thousands of soldiers’ graves on foreign fields led to the foundation of the Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission in 1917.

After the Armistice, the Commission began to organise the burial grounds and memorials to the fallen. As the battlefields were cleared, bodies were recovered and many were moved to ‘concentration’ cemeteries. Other battlefield burials were left in situ and the sites formalised.

Many families wanted to be allowed to put up personal memorials or get bodies sent back home for burial. Public objections were raised on the grounds that only the wealthy would be able to afford to do this. So the government ruled that the dead would remain where they had fallen.

Cemeteries

Three leading architects of the day - Sir Edwin Lutyens, Sir Herbert Baker and Sir Reginald Blomfield - prepared cemetery designs for the Commission. Cemeteries included a Cross of Sacrifice and a Stone of Remembrance to represent those of all faiths and those of none.

Headstones replaced all the temporary grave markers. The stones were all the same shape and colour, with no visible distinction of rank or wealth. The Commission wanted to emphasise the idea of a fellowship in death; a brotherhood that encompassed all classes, races and beliefs. Families were, however, allowed to choose a personal inscription for the stone.

The cemeteries themselves were tranquil gardens with immaculate lawns and planting.

The missing

Unidentified soldiers were buried with the same solemnity as the known. And all missing soldiers were individually recorded on memorials close to where they fell.

The huge building programme began in 1920. It did not finish until 1938, a year before the start of the Second World War (1939-45). Many of the cemeteries created by the Commission eventually became sites of pilgrimage and tourism.