Changing attitudes

For thousands of years, memorials have been erected in honour of great military victories and leaders. However, for much of history, ordinary soldiers were largely ignored.

This changed during the 19th century when the development of democratic ideals, combined with changing attitudes towards death, resulted in a growing recognition of the contribution and sacrifice of servicemen in war. However, it would take the catastrophic losses suffered during the First World War (1914-18) before these individuals would take centre stage in commemorations.

In Britain, this process would be shaped by two factors; the huge numbers of men whose bodies either could not be found or identified; and the decision not to bring bodies home, but to bury them in special cemeteries near where they had fallen.

First World War burials

Burying fallen servicemen on the Western Front was extremely challenging. It could usually only be undertaken when a lull in the fighting allowed bodies to be recovered. Hastily dug graves sprang up in widely scattered and often unsuitable locations.

David Railton, the Army chaplain who first put forward the idea of the Unknown Warrior as a symbol of all those lost during the conflict, took his inspiration from a rough wooden cross he encountered in France in 1916, on which was inscribed: ‘An Unknown British Soldier of the Black Watch’.

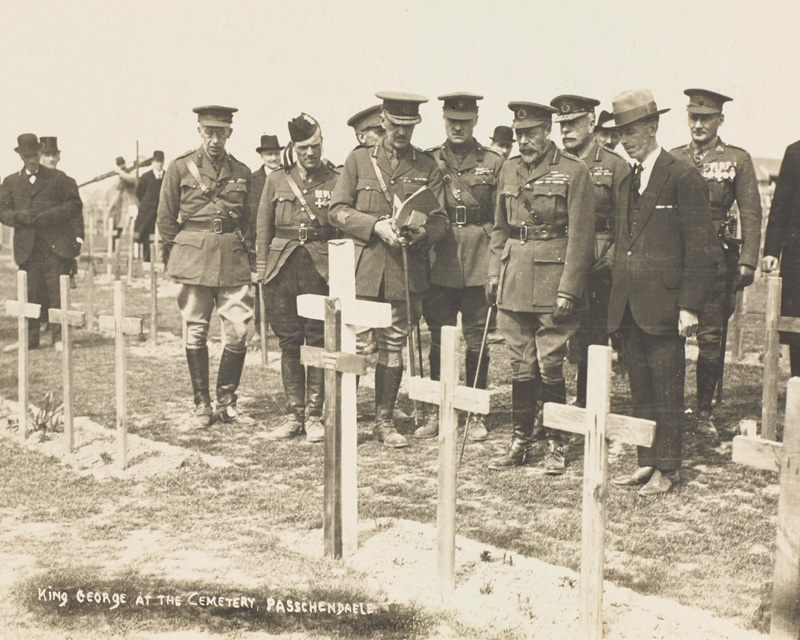

By the end of the war, thousands of British Empire servicemen lay buried in far flung theatres of war, including Africa and the Middle East. Such was the extent of this problem that King George V declared, ‘We can truly say that the whole circuit of the Earth is girdled with the graves of our dead.’

Graves Registration Units carried out the difficult and sombre task of recording and caring for the graves of fallen servicemen. This work was vital to maintaining the morale of both the troops still at war and the families at home, desperate for information about their fallen loved ones.

David Railton’s Union Flag

Inspired by the words of Chaplain David Railton, this short animated film reveals the moving story behind the flag that adorned the coffin of the Unknown Warrior.

Imperial War Graves Commission

A new organisation, the Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission (IWGC), was founded in 1917 to tackle these challenges. The Commission was responsible for a huge programme of cemetery building. This focused on the war-ravaged countryside of the Western Front, but also encompassed many other sites around the world.

The cemeteries were designed by prominent architects and aimed to incorporate the principles of equality, individuality and cultural sensitivity. They featured standardised headstones, together with common architectural features and immaculate lawns and planting.

To commemorate the missing, the Commission built memorials on which soldiers’ names were listed. The largest of these, the Menin Gate at Ypres and Thiepval Memorial on the Somme, list tens of thousands of names.

These cemeteries and memorials continue to be important sites of pilgrimage for bereaved families and are a powerful testament to the terrible sacrifice of war.

Bereaved families

The decision not to bring home the bodies of fallen servicemen was intended to ensure equality of treatment for all bereaved families. However, it provoked a bitter public controversy which revolved around the profound ethical and legal question of who had ownership of the dead. The IWGC received many impassioned letters on this subject from bereaved widows and mothers.

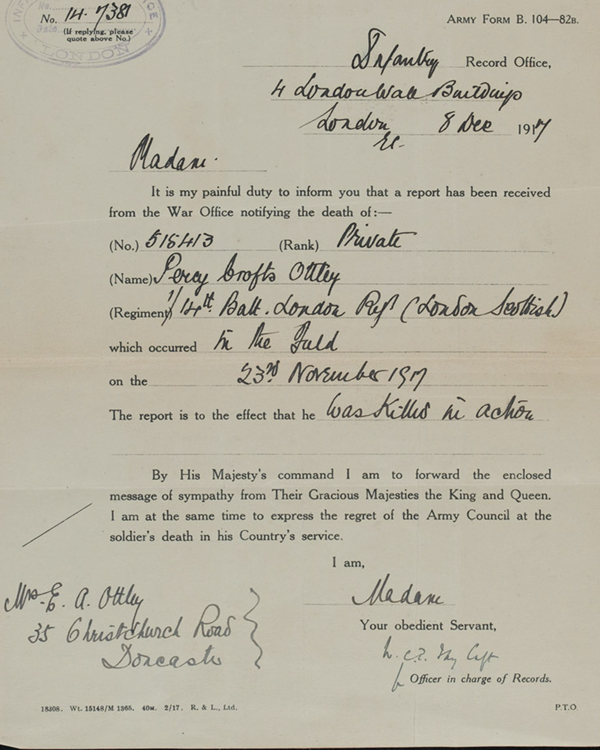

Most often, families would first be notified of a death through the receipt of Army Form B104-82B. Many would also receive a letter from the soldier’s commanding officer. These letters were often formulaic, aiming to provide comfort by emphasising the man’s popularity and good character, and by describing how their death was swift and painless.

Families would also be presented with the British War Medal and Allied Victory Medal, the two most commonly awarded medals of the First World War. Every bereaved family would have received the commemorative medallion, known as the ‘dead man’s penny’, together with a facsimile letter from the King and a commemorative scroll. These objects, together with letters and photographs, formed domestic shrines to the dead which adorned cupboards and mantlepieces across the country.

Local and national commemoration

The IWGC’s cemeteries and memorials were a magnificent commemorative achievement. However, as they were located overseas, they were largely inaccessible to Britain’s many bereaved families. This practical need for memorials closer to home, at which the families of the fallen could grieve, merged with a more general public desire to honour the dead and to ensure that their sacrifice was never forgotten.

While these feelings had certainly found expression during wartime, it was the end of the fighting that saw a huge outpouring of grief and the emergence of a wider culture of commemoration. Armistice Day, 11 November, became the focal point and new traditions emerged, including the wearing of poppies and the observing of a two-minute silence.

The trigger for this surge of poignant emotion and commemorative activity was the creation of Britain’s twin national war memorials, the Cenotaph on Whitehall and the grave of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey. However, its most far-reaching expression was the vast number of local memorials erected all over the country.

In the years immediately after the war, nearly every village, town and city in Britain built at least one public war memorial. These took many forms, but the most common were stone crosses, cenotaphs and obelisks. Usually sited in prominent and accessible places, these memorials provided locations for remembrance ceremonies.

The Cenotaph

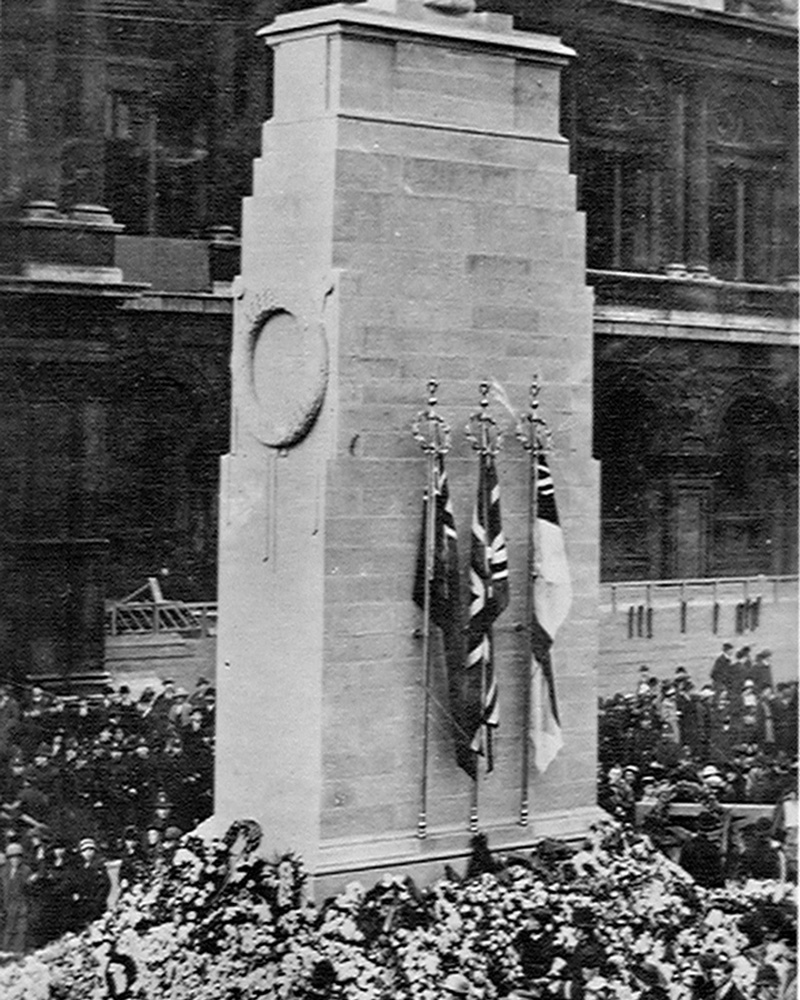

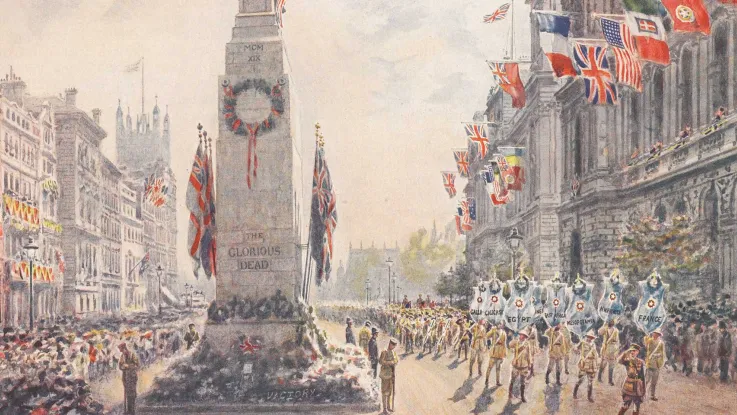

To mark the formal ending of the war, the government organised a national celebration on 19 July 1919. The highlight of this ‘Peace Day’ was a military parade in London comprising 15,000 Allied troops. Over five million spectators attended. The most solemn and moving part of the parade was a silent march past the newly built Cenotaph in salute of the war dead.

Designed as a temporary structure of wood and plaster by the architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, the Cenotaph was a simple and secular monument. Its name was derived from the Greek for ‘empty tomb’, a clear allusion to the missing who never came home.

Its original function was to serve as a saluting point for the military parade. However, it proved to be overwhelmingly popular with the public as a focal point for mourning and remembrance. Calls quickly grew for a more permanent version to be made in stone.

The Unknown Warrior

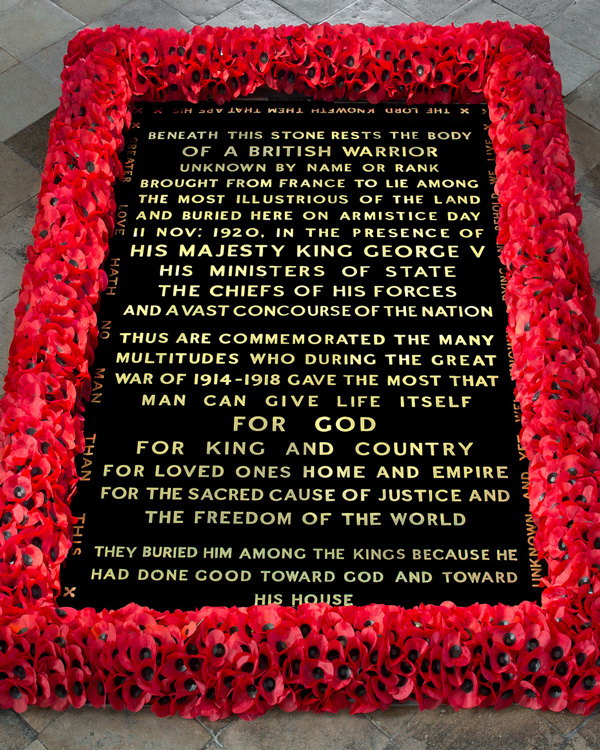

The newly rebuilt Cenotaph was unveiled on 11 November 1920 during the funeral procession of the Unknown Warrior. Earlier that year, the remains of an unidentified British serviceman had been disinterred on the Western Front and then returned home to Britain with great reverence and ceremony.

As the Unknown Warrior’s coffin passed by, en route to his final resting place in Westminster Abbey, and as ‘Big Ben’s’ chimes marked the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, King George V released the two huge Union Flags that had been concealing the Cenotaph. There then followed a two-minute silence - an occasion of immense poignancy.

When the procession arrived at Westminster Abbey, a service had already been under way since 10am. The congregation included nearly 1,000 mothers and widows of those who had died in the war. The place of honour went to a group who had lost both husbands and sons.

In a letter to a newspaper, one bereaved mother described how tears came to her during the service ‘mingled with gladness, for in that beautiful building and that music that thrilled my soul I felt very near to my lost boys’.

Grief and loss

Inspired by the thoughts and feelings of mothers who have experienced the loss of a child during war, this short animated film explores the subject of remembrance.

Public view

For a week after the burial, the Abbey was kept open to allow the public to view the grave. During this time, four sentries - one each from the Army, the Royal Navy, the Royal Marines and the Royal Air Force - were posted to each corner, standing with heads bowed and with arms reversed. It is estimated that well over one million people had filed past the Unknown Warrior by the time his grave was filled in on 18 November.

On Armistice Day the following year, a Union Flag belonging to Chaplain David Railton, which had adorned the Unknown Warrior’s coffin during the funeral, was dedicated in a special ceremony and hung on a pillar near the grave. It was moved to the Abbey’s St George’s Chapel in 1964, where it remains to this day.

The grave of the Unknown Warrior, Westminster Abbey, c2019 (By kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

The Unknown Warrior's grave in Westminster Abbey, c2019 (By kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

Healing and remembrance

The Unknown Warrior remains highly revered today. His is the only one of the Abbey’s many floor graves that is never walked over, even during processions.

But perhaps his greatest importance lies in his special role in healing the bereaved. He provided a symbolic funeral and a surrogate grave for all those who had been denied these comforts. His anonymity allowed all the families of the missing to believe that it was just possible that he was their relative.

Along with the Cenotaph, and the thousands of memorials in towns and villages across the country, the Unknown Warrior helps us remember the sacrifice of the nation's soldiers during the First World War.