Opening salvo

On 16 December 1914, residents of the town of Scarborough on the North Yorkshire coast awoke to a dank and misty morning. As they set about their daily routines, an unexpected sight appeared on the horizon: the unmistakable outlines of three warships.

From his seafront house on Queen’s Parade, Mr Crossland had a clear view of proceedings. He assumed that these ships - so close to the shore that he could see sailors on their decks - were part of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet on manoeuvres in the North Sea. Then, at around 8.00am, suddenly and chaotically, a shell ‘came hurtling through the roof of the house... the room was left in intolerable confusion, and holes were torn in walls’.

This was the opening salvo of the German Navy’s surprise attack on the towns of Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby along England's north-eastern seaboard, and the remarkable moment that the First World War reached the British mainland.

Impact

Earlier that morning, a fleet of four German battlecruisers, an armoured cruiser, four light cruisers, and 18 destroyers had left their base at Heligoland as part of a daring raid that sought to exploit a gap in Royal Navy defences.

At Scarborough, SMS 'Derfflinger' and SMS 'Von der Tann' fired more than 500 shells, hitting the town’s historic castle, the Grand Hotel, as well as numerous houses and churches. Shortly afterwards, an even larger assault began on the port of Hartlepool, where the steelworks, gasworks, railways, seven churches and over 300 houses were struck.

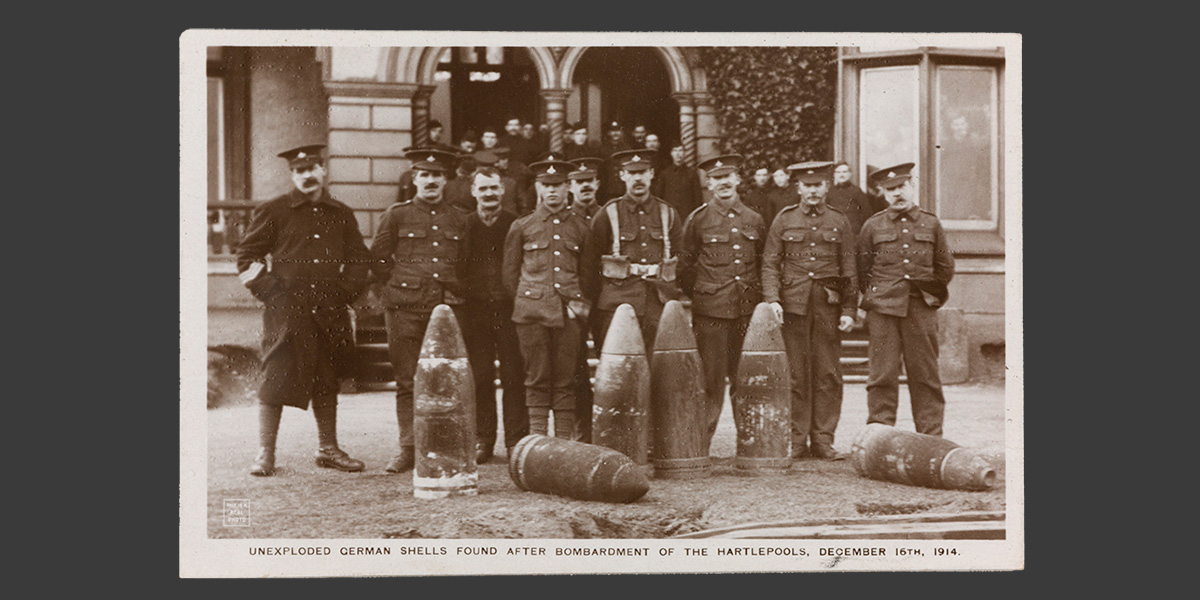

After some initial confusion, men of the Durham Royal Garrison Artillery returned fire from batteries on the coast, scoring one direct hit on the SMS 'Blücher'. Finally, at around 9.30am, another German salvo was fired in the direction of Whitby, before the ships made for home.

British soldiers with unexploded shells found after the bombardment of Hartlepool on 16 December 1914 (Image: IWM (HU 128024))

Casualties

In all, more than 130 people were killed; several hundred others were injured. There had not been an attack against Britain’s home defences on such a grand scale since the Dutch Republic's raid on Chatham Dockyard in 1667.

Notably, this was first time that Kitchener’s ‘New Army’ troops came under fire during the war, with seven members of the Durham Light Infantry killed in the line of duty. Private Theophilus Jones, aged 29, was the first British soldier to die as a result of enemy action on British soil for over two centuries.

Outrage

Across Britain, there was outrage at what appeared to be an unprovoked attack on civilians (although some historians have since suggested that the targets were primarily strategic), as well as the failure of the Royal Navy to stop it.

In the national press, writers condemned the immorality of the raid and gave voice to an increasingly prevalent anti-German sentiment. The following year, several British towns and cities would experience riots targeting German immigrants and businesses.

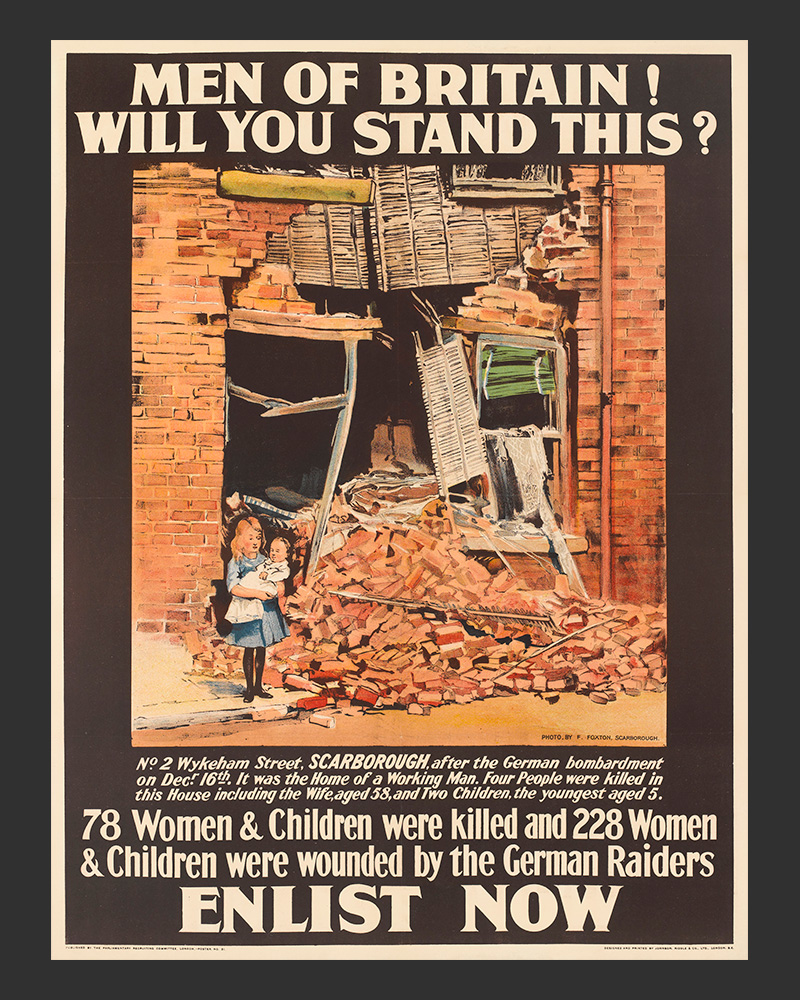

This impassioned public response was not lost on the British government, who made the raid the subject of a propaganda campaign. In 1915, military recruitment posters called upon the people of Britain to ‘Remember Scarborough!’ in the fight against the ‘German Barbarians’.

Small victories

Inevitably, the reaction in Germany was quite different. The attack had been envisioned as a means of retaliation following the German Navy’s defeat at the Battle of the Falkland Islands (8 December 1914) the week before. Despite its military insignificance, the raid was celebrated as a victory for the German Empire and an all-important morale boost.

A small silver medal was struck to honour the occasion, part of a series commemorating various battles and wartime successes. The reverse of all these medals is inscribed either, ‘Gott segnete unsere tapferen Heere’ (‘The Lord blessed our valiant armies’) or, as in this instance, ‘Gott segnete die vereinigten Heere’ (‘The Lord blessed the united armies’). The dictum surrounds an embossed image of the figure of Nike, goddess of victory.

On the obverse of this example is the phrase ‘Beschiess. von Scarborough u. Hartlepool durch Deutsche Schiffe 16. Dez. 1914’ (‘Bombardment of Scarborough and Hartlepool by German ships 16 December 1914’). It seems likely that the medal was intended for both veterans and civilians in support of the German war effort.

Bombardment of Scarborough, commemorative medal, 1914 (Image: IWM (Art.IWM MED 446))

Striking parallels

Interestingly, the Birmingham Mint struck its own medal to commemorate this event, complete with the seal of Scarborough in the centre, views of the town at the sides, and three ships at sea firing towards the coast at the top. It proclaimed ‘Scarborough Still Undismayed’ on the ribbon below and ‘Bombardment of Scarborough & Non Combatants By The German Fleet Dec. 16 1914’ on the reverse.

The similarities with its German equivalent demonstrate the extent to which propaganda efforts informed the design of medals during the First World War.

Discover more

Visit our Army at Home gallery to find out more about the important role that soldiers have played in protecting the British Isles from naval and aerial attacks.