German aerial incendiary bomb on display, 2023

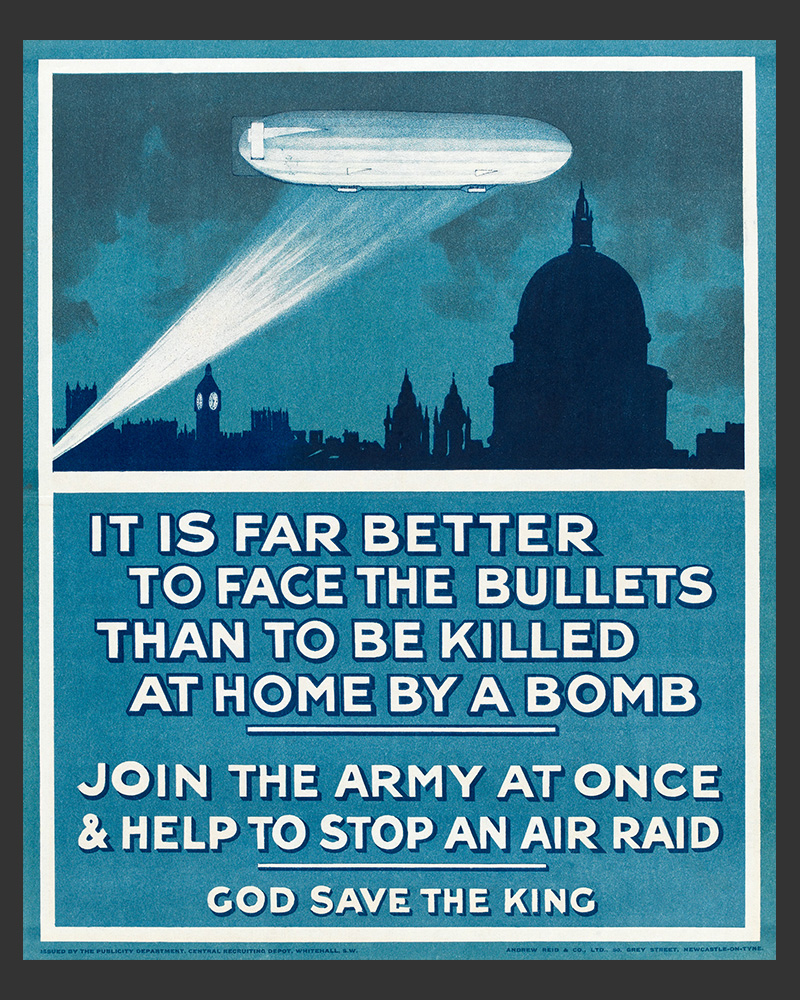

Terror from the skies

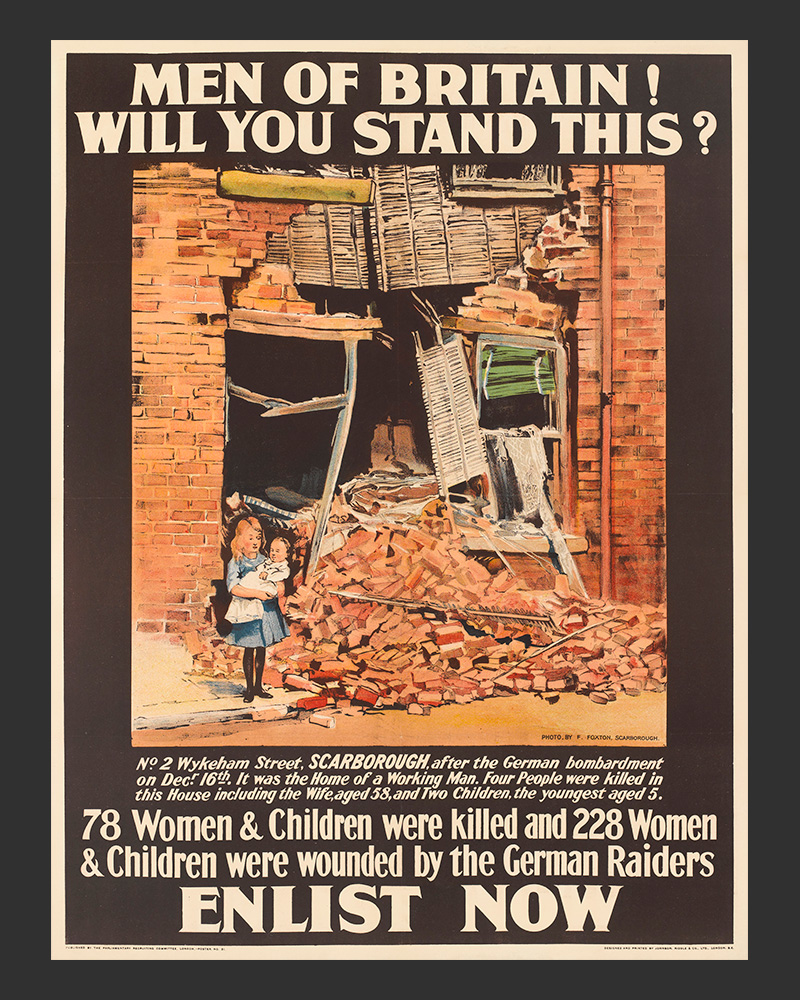

In January 1915, the German armed forces began an aerial bombing campaign over Britain. Along with the previous month’s naval bombardment of Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, this was the first time in over a century that a foreign power had successfully launched an attack on the British Isles.

The first aerial bombs fell on coastal towns in Norfolk. Over the course of the war, thousands more were dropped - primarily from Zeppelin airships - on London, the Home Counties, the Midlands and the north-east of England. Around 2,000 people were killed or wounded.

Impact

Aerial bombing was an imprecise business, largely at the mercy of the weather. Many bombs landed miles from their intended targets. Although airships were superseded by more reliable aeroplanes later in the war, the German campaign had little strategic impact. British war production was barely interrupted.

The psychological effect on the British public, however, was considerable. The government capitalised on the initial shock and outrage at the targeting of civilians in their homes, encouraging people to join up and fight back.

Meanwhile, efforts to introduce aerial defence measures led to a disproportionate allocation of military resources, including Royal Artillery batteries and Royal Flying Corps squadrons.

Damage

The bomb on display in our Conflict in Europe gallery consisted of an inner cylinder packed with thermite, surrounded by a metal container filled with flammable benzol. The charge would ignite on impact. An outer layer of coiled rope, reinforced with wire and covered in tar, would then keep the device burning after the initial chemical reaction had subsided.

This example was certified free from explosives in 2003, so no longer posed a hazard. Its heavily misshapen curved outer panel had become partially detached from the main body. There were also numerous holes and warped bits of wire in the outer panel, and the metal was heavily corroded both inside and out.

Treatment

Prior to conservation, we were keen to understand more about how these bombs functioned in order to determine whether or not all the parts were original.

The metal wire at the top was one of the parts we were initially unsure about. However, our research revealed that this was indeed part of the original design, and that it would have had a cloth streamer attached to facilitate a steady descent.

Following testing, the bomb was treated chemically with a corrosion converter. This reacts with the iron oxides to form a blue-black film, which protects the surface from further corrosion.

We were keen to preserve the bomb’s damaged condition as this serves as vital evidence of its destructive history. Stabilising the corrosion was therefore the full extent of the treatment required to make the object ready for its display environment.

The bomb before treatment

And after treatment

See it on display

This bomb gives visitors an insight into the early years of aerial warfare. Its story also foreshadows many features of home defence that were to surface more prominently during the Second World War.

Come and see it in our Conflict in Europe gallery, displayed alongside other items that reveal the rapidly changing nature of warfare in the early 20th century.