Assassination

On 28 June 1914, Arch-Duke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo by a Bosnian-Serb. His death sent a shockwave through Europe’s intricate alliance system and saw the major powers prepare for war.

Throughout July 1914, the British Army prepared for mobilisation as the crisis deepened. Army leave was cancelled, Reservists were called up and units placed on alert.

War declared

Germany’s war plan was based on a quick strike against France while Russia, France’s ally, was slowly mobilising. On 1 August 1914, the Germans declared war on Russia. Three days later they invaded Belgium in order to attack France.

This violation of Belgian neutrality led to a British declaration of war on Germany on 4 August and mobilisation of the armed forces. Eight days later, war was declared against Austria-Hungary and three months later against the Ottoman Turks.

A popular cause

Although many people were shocked and fearful, the outbreak of war was largely greeted with popular acclaim in Britain. The public rallied around what they perceived to be a just cause.

Around 30,000 men were enlisting every day by the end of August. Neither the Second World War (1939-45) nor more recent conflicts have generated anything like this degree of enthusiasm.

‘In the evening we went to a theatre on the Strand. The noise of newsboys and shouts of the crowd made it impossible to fix one’s attention on the play. At 11pm terrific bursts of cheering could be heard outside, echoing and resounding from Trafalgar Square to Westminster and Buckingham Palace. We left the theatre and walked to the Palace… There was a crowd of thousands collected in the hopes of hearing the King speak from the balcony; the cheering was such as I have never heard before nor expect to hear again. It was known that war had been declared against Germany… the crowds did not disperse till early morning. One of the most memorable nights in history’.Diary of Lieutenant Charles Mosse — 4 August 1914

The Army on the eve of war

Britain went to war in 1914 with a small, professional army that was primarily designed to police its overseas empire. The entire force consisted of just over 250,000 Regulars. Together with 250,000 Territorials and 200,000 Reservists, this made a total of about 700,000 trained soldiers. This was tiny when compared to the mass conscript armies of Germany, France and Russia.

Although small, the Regular Army of 1914 had learned from the harsh lessons of the Boer War (1899-1902). Reforms in training had been introduced which meant that, man-for-man, the soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were among the best in Europe.

‘It looks as if the greatest battle in the history of the world will soon be in progress… We haven’t the slightest idea what the future holds for us yet but we are likely to be in uniform for at least a few months.’Letter from RSM Arthur Harrington to his wife — 13 August 1914

Territorials and Reserve

Each Regular Army regiment and corps had locally recruited Territorial Force (TF) units attached to it. Men trained during the evening, at weekends and at summer camp. In the event of war they could be called upon for full-time service. Territorials were not obliged to serve overseas, but when asked in August 1914, the vast majority agreed to do so.

There was also the Special Reserve (SR), whose men enlisted for six years and could be called up in the event of general mobilisation. Their period as a Special Reservist started with six months full-time training, followed by four weeks training per year. There were over 100 Reserve battalions in August 1914. They went on to provide reinforcement drafts for the active service battalions on the Continent.

New Armies

While many expected the war to be ‘over by Christmas’, the Secretary of State for War, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, realised the conflict would be long and on an unprecedented scale. Britain would have to create a mass army for the first time.

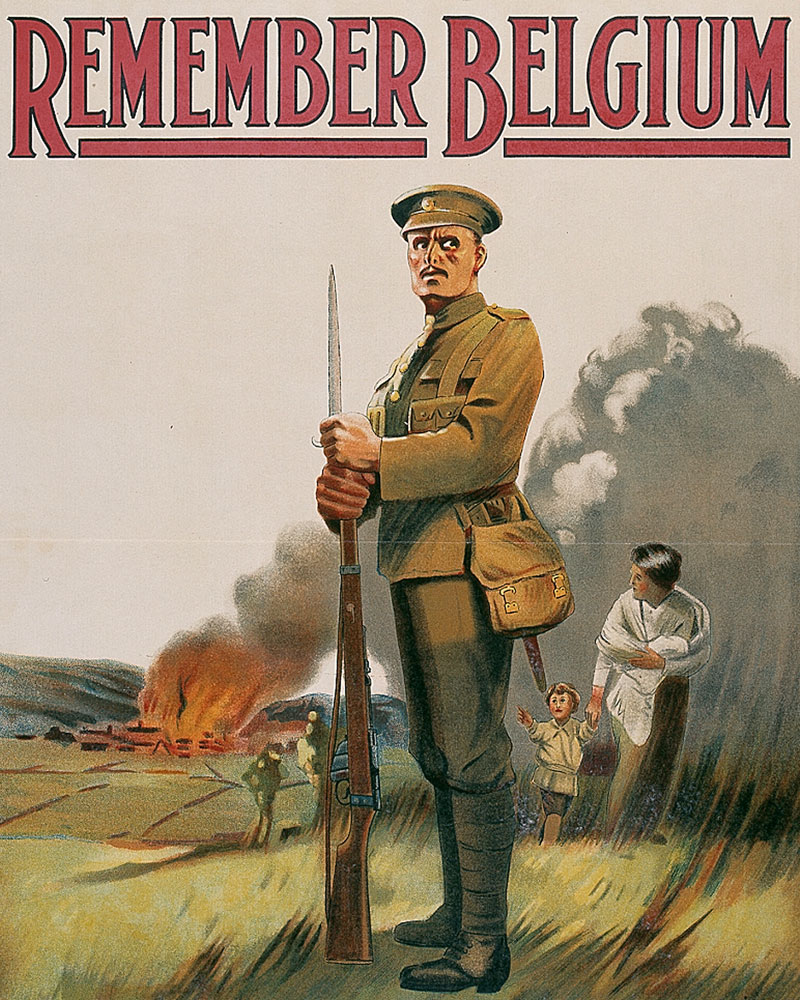

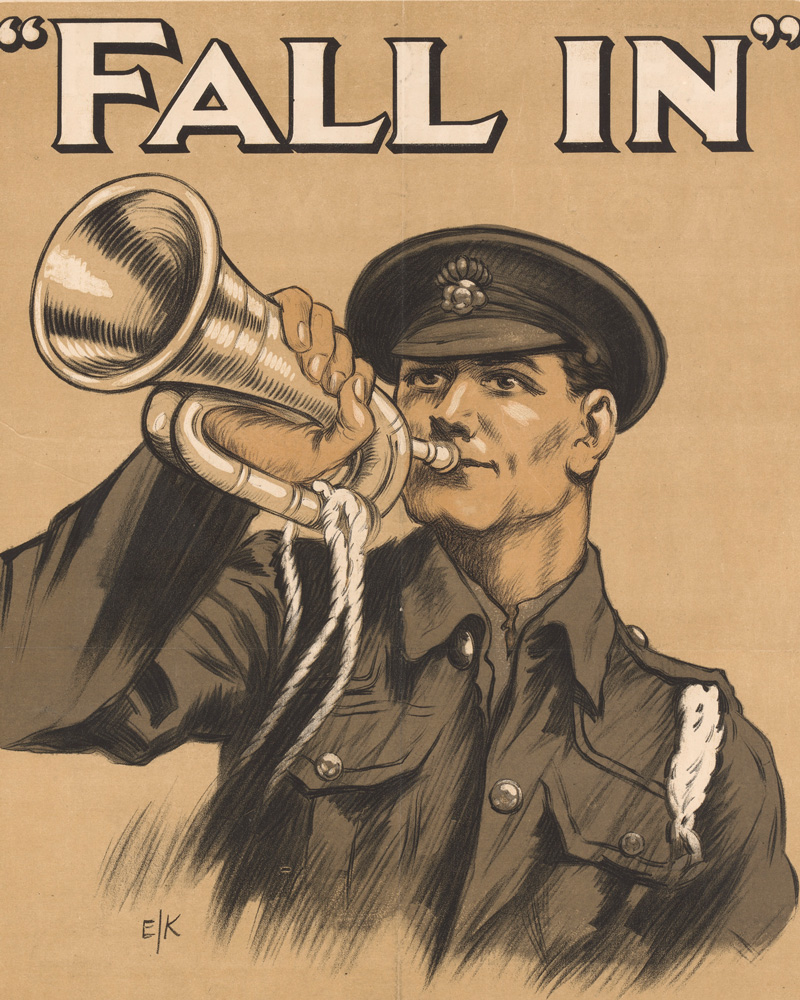

He therefore appealed for volunteers for his ‘New Armies’ in August 1914. Recruitment officers were sent to towns, cities, factories and clubs. Propaganda posters were placed all over the country to persuade men to sign up.

These volunteers enlisted ‘for the duration of the war’. They had a choice over which unit they joined, but had to meet the same age and physical criteria as the Regulars. Men who had previously served in the Army were accepted up to the age of 45. Despite the regulations, many underage and overage men enlisted.

Pals

Men often joined ‘Pals’ battalions, organised on a local basis. The advantage of this was that the new battalions came with existing ties, which the Army could develop. The disadvantage was that if a unit suffered heavy casualties, it could have a devastating effect upon a community.

The thousands of eager volunteers who flocked to the Colours on the outbreak of war were completely untrained. They spent their first months in the Army learning the basics of soldiering. Drill, skill-at-arms and manoeuvres were learnt at huge camps situated all over the country.

The ‘New Armies’ would face their baptism of fire in the battles of 1915-16. Until then, the Regulars - supported by the TF and SR - would take the leading role.