Adventurer

Roger Courtney was born in England in 1902. In the 1930s, he went to Africa in search of adventure, finding work there as a big game hunter and gold prospector.

During his time in Africa, Courtney also became a keen canoeist. He paddled the length of the Nile equipped only with an elephant spear and a sack of potatoes. Such was his enthusiasm for canoeing that in 1938, he and his wife Dorrise paddled along the Danube for their honeymoon.

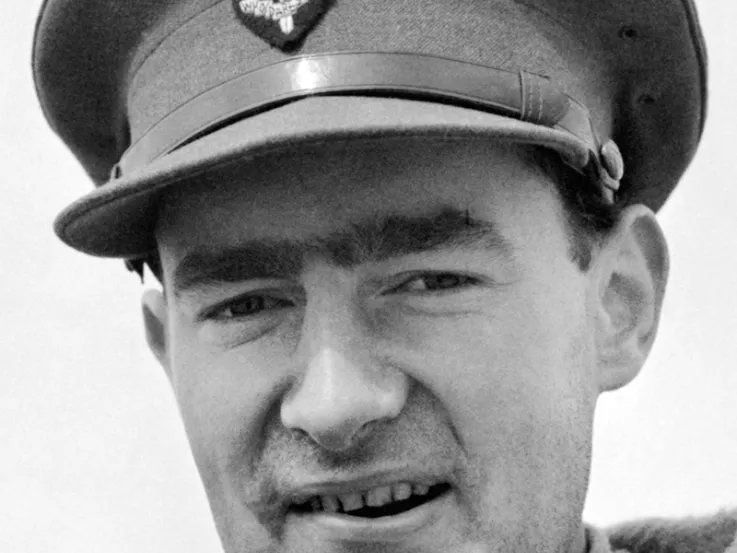

Captain Roger Courtney with his dog, 1943 (© John Robertson)

Sense of humour

Courtney was a rough, tough, larger-than-life character with a great sense of humour. During a brief spell back in Britain in the 1930s, he was involved in a much-publicised hoax at Loch Ness. He used the foot of a hippopotamus he had killed in Africa to leave prints mimicking those of the fabled local monster. This created a sensation in the press.

One of his wartime officers described him as having a ‘bashed-in kind of face and a blunt, no-nonsense manner that was intimidating on first meeting. Fortunately, that was soon dispelled by a great bellowing laugh’.

Courtney served as a sergeant in the Palestinian Police during the Arab Revolt of the late 1930s. He also had a flair for writing, publishing several books about his adventures in Africa and Palestine.

War

On the outbreak of war, Courtney returned to Britain and joined the King's Royal Rifle Corps. In 1940, his intrepid spirit inspired him to volunteer for the Commandos, Britain’s new amphibious raiding force.

Drawing on his canoeing experience, he formulated the revolutionary concept of using small collapsible canvas canoes, known as folboats, to conduct sabotage raids and reconnaissance along enemy coastlines.

Canoes

Courtney recognised that canoes offered great advantages in stealth and secrecy. They were silent, had a low silhouette and were highly portable. But, despite being known for his forceful manner and persuasive tongue, he was unable to win over senior officers.

For many, the idea of operating in small, flimsy boats in perilous coastal waters seemed crazy. And so his initial request to form a new unit was turned down.

Proof of concept

Undeterred, Courtney sought to prove the worth of his methods by conducting a covert attack on a British ship, HMS ‘Glyngyle’, anchored in the Clyde estuary.

Under cover of darkness, he paddled up to the vessel in his canoe, scaled the anchor chain, infiltrated the ship and stole the cover from a deck gun as proof of his success.

Returning dripping wet, he burst into a hotel where a group of senior naval officers were having a meeting and presented them with the gun cover.

SBS formed

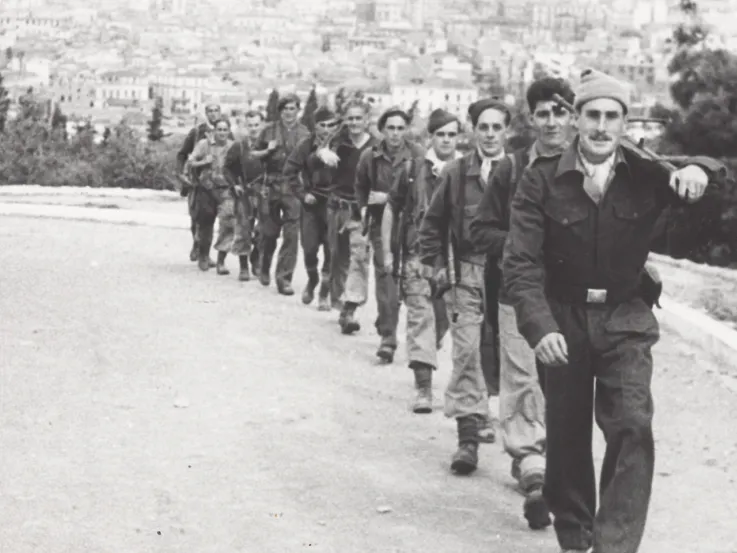

Following this success, Courtney obtained authorisation for another mock attack, which again vindicated his ideas. He was promoted to captain and given permission to raise a unit of 12 men, initially called the ‘Folboat Section’, but later renamed No 1 Special Boat Section (SBS).

Courtney’s men began intensive training around the Isle of Arran. Here, they mastered swimming, canoeing and a host of other skills, including navigation, survival, demolitions and signalling. All would be vital to their success.

A Combined Operations Pilotage Parties canoe, c1944 (© IWM (MH 22716))

Rhodes

Early in 1941, Courtney’s team sailed with the commando group ‘Layforce’ for the Middle East. Layforce’s first objective was to mount an amphibious assault on the Italian-held island of Rhodes.

The planning of this Mediterranean mission provided the first opportunity to test Courtney’s methods. He teamed up with a naval officer, Lieutenant Commander Nigel Clogstoun-Wilmott, to undertake the first in-depth covert beach reconnaissance in military history.

Narrow escape

Operating from a submarine, they made a series of daring night-time canoe reconnaissance missions to the island. On the last of these, Courtney only narrowly escaped capture. Seized by a violent cramp in his leg, his agonised writhing on the beach drew the attention of a local dog, which almost blew his cover.

Both men were decorated for this success, Courtney winning the Military Cross. While the attack on Rhodes never took place, they had established the value of using canoes in this vital reconnaissance role. This was to lead Clogstoun-Wilmott to form his own special force, the Combined Operations Pilotage Parties, to carry out this kind of work.

Raids

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Robert 'Tug' Wilson, Courtney’s second-in-command, pioneered the other SBS specialism: sabotage on enemy coastlines. Also operating with canoes from a submarine, Wilson and Marine Wally Hughes, mounted a series of successful raids against railway infrastructure along the Italian coast.

The SBS facilitated other special forces work, most notably deploying commandos on the coast of Libya in an ill-fated attempt to kill the German general Erwin Rommel in November 1941.

They also supported the espionage work of the Special Operations Executive by transporting secret agents to and from enemy territory.

Return to Britain

Suffering from ill health, Courtney returned to Britain in 1942. Here, he took up an administrative post and worked on the establishment of 2nd Special Boat Section.

This unit saw service in Europe and the Mediterranean, where it assisted in Operation Torch, the invasion of French North Africa.

Later in the war, the unit was despatched to the Far East. Following its re-organisation, Courtney was sidelined and given a new posting in Somaliland.

Special Boat Squadron

Meanwhile, the 1st Special Boat Section continued to operate in the Mediterranean, briefly under the Special Air Service, then evolving into the Special Boat Squadron in 1943.

Under the command of Captain George Jellicoe, it unleashed a reign of terror along enemy coastlines. This forced the Axis to divert thousands of scarce troops to carry out defensive duties.

‘It was with [Courtney] that just anything could be tackled. The impossible became downgraded to improbable, then probable, and finally almost a piece of cake.’Lieutenant Robert 'Tug' Wilson

Legacy

Courtney died in Somaliland in 1949, but his legacy lives on today in the modern Special Boat Service. Alongside its traditional roles of raiding and reconnaissance, this unit is also Britain’s primary defence against maritime terrorism.

A Special Boat Service Rigid Inflatable Boat, c2010 (© Crown)