Women’s roles in the Army

Women have always performed roles in the Army's operations, as wives, cooks, nurses, and even as prostitutes. But, despite the emergence of professional military nursing services and a handful of female voluntary organisations, it was not until the First World War (1914-18) that women were fully mobilised.

Military nursing

During the First World War, women of the Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS) cared for wounded and sick soldiers in Britain and overseas. They worked in field hospitals, aboard ambulance trains, hospital ships and barges and in casualty clearing stations.

QAIMNS was supplemented by the Territorial Force Nursing Service, established in 1909. All of its members worked as nurses in civilian life. Combined, these organisations expanded from around 3,000 nurses in 1914 to 23,000 in 1918.

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) was another unit that provided medical support. Formed in 1907, the FANY was modelled on military lines. It included 'Yeomanry' in its title as its members rode horses.

Volunteers paid to join the FANY and had to cover their own expenses for uniforms, first aid kits, riding school fees and horse care. This meant only wealthy women enrolled.

Initial setback

The FANY was seen as something of a paradox at the time. Although nursing was an established female role, wearing military uniforms and serving on battlefields was the preserve of men. Some even associated female militarism with radical elements of the women’s suffrage movement.

On the outbreak of the First World War, the FANY offered its services to the British authorities. But, despite positive recommendations from serving officers, their offer was turned down.

Consequently, it was in order to provide nurses and ambulances for the Belgian Army, and soon afterwards for the French, that the first FANYs crossed the Channel in October 1914. It was the first British women’s voluntary organisation to go out to the war.

They worked in hospitals and evacuated injured civilians and soldiers during bombardments and air raids. They also set up soup kitchens and visited trenches to hand out knitted hats and socks to Belgian soldiers. But what started for many as an adventure quickly changed with the grim realities of war.

‘The sight was one that I shall never forget but find it almost impossible to describe. Four men had been blown to pieces… and it gave me an intense shock to realise that a few minutes earlier those remains had been living men walking along the road laughing and talking. I felt suddenly sick.’Pat Waddell, Fanny Went to War — 1919

Changing attitudes

The women of the FANY had to deal not only with the horror of the war, but also with prejudice from the military authorities. It was not until January 1916 that the British finally recognised the value of their support, and they became the first women to drive motor vehicles for the British Army.

Alongside other women’s organisations, like the Voluntary Aid Detachments, their contribution helped convince the War Office of the value of women in the armed services, and was a factor in the Women’s Royal Naval Service and Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps being founded in 1917.

Today, the FANY (Princess Royal’s Volunteer Corps) continues to support the civil and military authorities within the UK.

‘The Situation Is Serious’

Beyond nursing, there were many other women who felt they should be doing more for the war effort. On 21 July 1915, a march took place in London to persuade the authorities to widen women’s role in the war, using the slogan: ‘The Situation is Serious’.

The Government, faced with shortages of men in key industries, had no choice but to mobilise the whole population. And, by November 1918, over a million women had been added to the British workforce.

Women were initially recruited as bus conductors and train guards, and then as munitions workers. Many were injured in factory accidents. Others suffered from the chemicals they worked with, which turned their skin yellow, prompting the nickname ‘canaries’.

Expanding roles

In August 1915, Lady Londonderry helped establish the Women’s Legion to prepare food for the Army.

Based in Dartford, it provided cooks, waitresses, gardeners and, from 1916, motor transport drivers. The latter chiefly served with the Royal Flying Corps.

It was not formally under Government control or part of the Army. But, in keeping with the spirit of the times, its members adopted a military-style organisation and uniform.

In February 1917, thanks to the pioneering endeavours of women like Florence Simpson, all 7,000 Women’s Legion cooks and waitresses were transferred into the newly formed Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

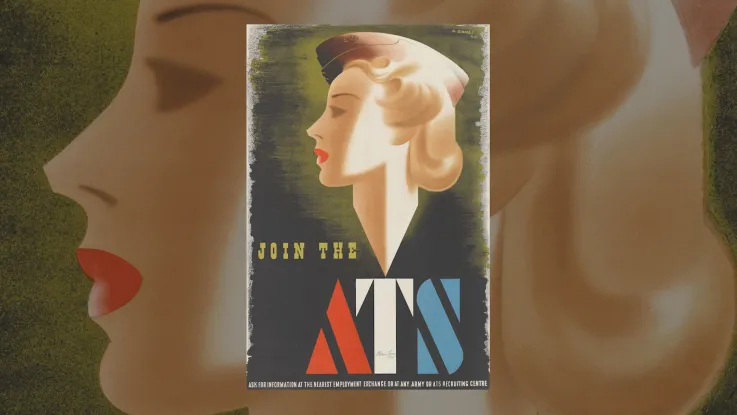

Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps recruitment poster, c1918

Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps

Despite the introduction of conscription in 1916, the heavy losses at the front meant the Army’s manpower shortage got worse. The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was formed to free up soldiers from non-combat roles so that they could go and fight.

Alexandra Chalmers Watson was appointed to lead the new force in Britain. She was the sister of Brigadier Auckland Geddes, the War Office Director of Recruiting.

A small contingent of the WAAC embarked for service in France in March 1917, under their first commander, Assistant Controller Helen Gwynne Vaughan. On arrival, Vaughan proved an able commander despite the obstruction of some male colleagues.

‘I discovered that the objection to the employment of women was almost universal. The Services, of all professions, had naturally the least experience of working with women, they knew little of the extent to which, even then, men and women were working easily together, they mistrusted the complications which the influx of a large body of women might entail, they disliked the intrusion into their offices and workshops of an alien element.’Helen Gwynne Vaughan, Service with the Army — 1941

A different status

Unlike male soldiers, the women of the WAAC 'enrolled' rather than 'enlisted'. This gave them a different status to men, more like that of civilians in uniform.

They also had a different command structure to their male counterparts. Officers were called ‘Officials’ (Administrators and Assistant Administrators), non-commissioned officers were referred to as ‘Forewomen’, and other ranks as ‘Workers’. So, in name at least, the WAAC resembled the factory structure familiar at home, rather than a military formation.

On His Majesty’s Service

The opportunity to serve in the Army was attractive to young women like Lia Parfitt, who later commented in her memoir:

‘In 1917, I began to see girls in khaki uniforms, these were… members of the WAAC. Then my evil spirit and restlessness began to catch up with me. I wanted to be a WAAC and do my bit – this was my usual theme of conversation whenever my poor father was home, and his usual answer was: "No, No, No!"

‘Unbeknown to my father, I wrote to the Recruiting Office of the WAACs and offered my services. Soon, a long envelope bearing the magic letters OHMS (On His Majesty's Service) came for me. It told me to report to the Board of Examiners for an oral examination and also a medical at Southampton. My father would happen to be home at the time and he hit the roof!’

Kitting out

The women were issued with uniform, as Florence Hill recalled:

‘I went to the Issue Room. My 5ft 2 inches [about 158cm] was quite a problem. Everything was much too big and WAAC greatcoats out of stock. By the time I got my uniform, it was a Tommy’s greatcoat for me… and it caused a lot of laughter when I put it on. The next step was the tailor's… Skirts in those days had to measure 8 inches [about 20cm] from the ground, so that tailor had a lot of work to do on my uniform.'

Jobs for the girls

Women were employed as cooks, mess waitresses, clerks, telephone operators, store-women, drivers, printers, bakers and cemetery gardeners.

Their work was much appreciated by their male colleagues. Private Thomas Fuller wrote in May 1918: 'The WAACs can cook much better than the old Army cooks used to, so we shall miss them when we go up the line.'

By 1918, nearly 40,000 women had enrolled. Of these, some 7,000 served in France on the Western Front, the rest in the UK.

Danger

On the Western Front, the WAAC often shared the same dangers as their male colleagues. Air raids on the camps and depots were frequent. At Abbeville, on 30 May 1918, nine women died. Marjory Peacock knew one of the dead, writing of her funeral:

'Graves in France were just long trenches so before Trixie was buried some of us went out into the woods and gathered daffodils and brought packets of hair pins from the canteen and went down into the grave and lined her part of it by pinning daffodils to the sides before she was buried.'

In May 1918, German aircraft attacked the WAAC camp at Abbeville. One of their bombs fell on a trench shelter killing 22-year-old Margaret Caswell and eight of her colleagues, and wounding a further seven.

Royal recognition

The rapid German breakthrough on the Western Front in Spring 1918 placed the WAACs in even greater danger. Forewoman Ada Gummersall recalled:

'In March 1918, our troops were driven out of their trenches and were in general retreat. It was an anxious time for all of us. We could hear the guns of the enemy quite close and were told by the Red Cross that arrangements were being made to evacuate us to England if necessary.'

The women were evacuated safely and the battle later turned in the Allies' favour. In honour of their conduct, Queen Mary became the unit's patron. On 9 April 1918, the WAAC was officially renamed Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC).

Public opinion

Female soldiers attracted a mixed reception from the press and public. Some wives and mothers resented their male relatives being replaced in their non-combat roles and sent to the dangers of the front line.

Several newspapers suggested that improper relations took place between women soldiers and 'Tommies'. This rumour persisted, despite a March 1918 investigation that found only 21 women had been sent home pregnant in the past year.

Surplus to requirements?

After the First World War, the Army was reduced to peacetime levels and QMAAC was no longer needed. The corps was disbanded on 27 September 1921.

The rise of Adolf Hitler and the growing threat of another global conflict in the 1930s led to the formation of further women's units. Many former QMAACs rejoined the newly created Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). Its members served with distinction in the true tradition of the female pioneer soldiers of the First World War.