Women’s roles

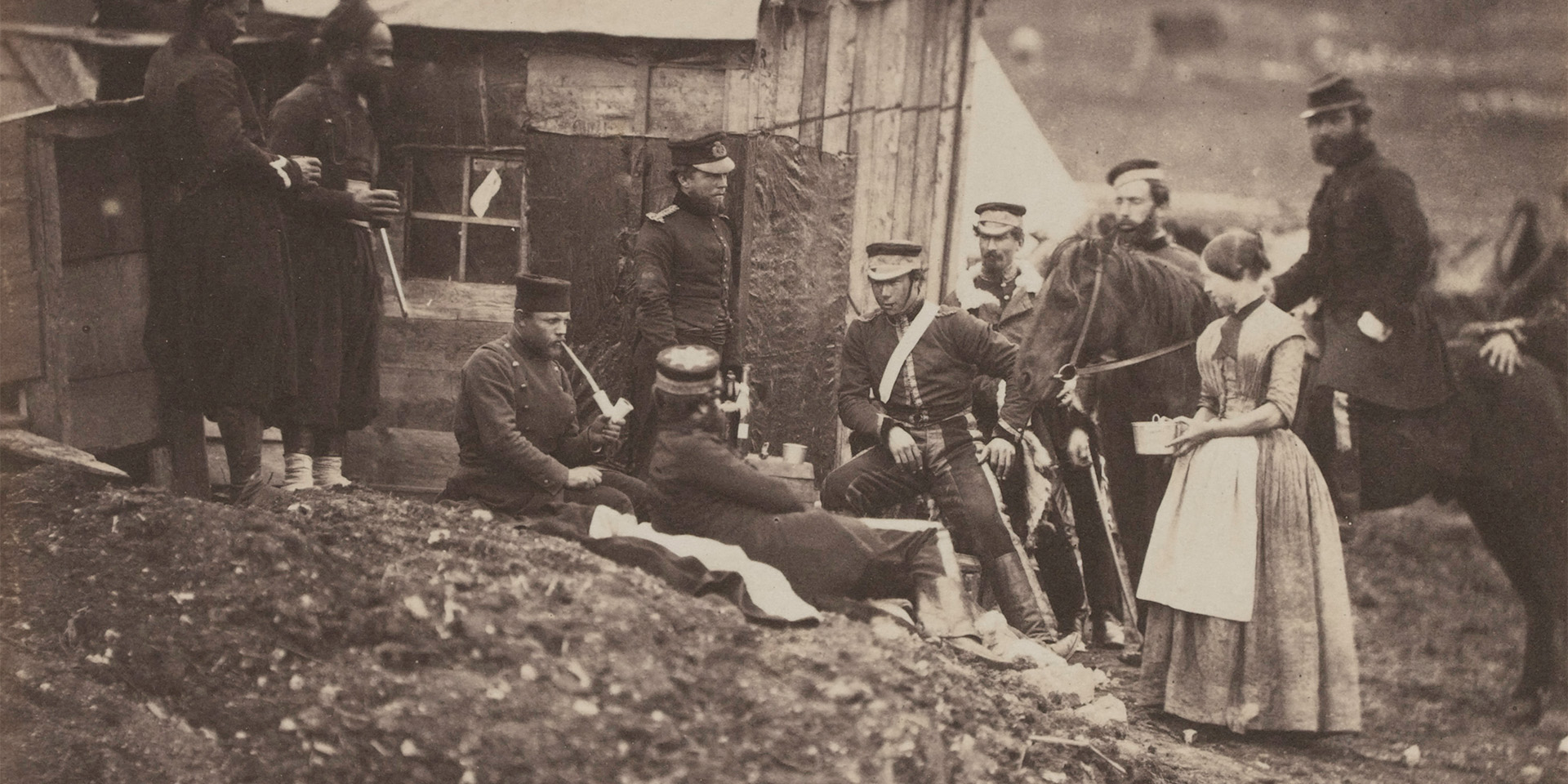

Until the 1850s, women held various unofficial roles in the Army: wives, cooks, nurses, midwives, seamstresses, laundresses, prostitutes, as well as ‘sutlers’, who traded in food and drink.

All lived with and around a regiment and even travelled abroad with it. They played a significant role in caring for the physical and emotional wellbeing of the men. But, with the increasing professionalisation of the Army during the second half of the 19th century, women found themselves more and more excluded.

Mrs Rogers

Mrs Rogers was the wife of a non-commissioned officer at the camp of the 4th Dragoon Guards during the Crimean War (1854-56). She acted as a cook and laundress for the regiment and was much admired for her bravery.

In a letter of June 1855, Colonel Edward Cooper Hodge described Mrs Rogers as deserving the Crimean Medal ‘ten times more than half the men who will get it’.

Cantinières on campaign

Cantinières were civilian women attached to the French Army on an official basis, who sold food and liquor to the soldiers above and beyond what they received as rations. They had to be married to a soldier of the regiment, and received no pay, living off their earnings instead.

The cantinière also played an important social role in the regiment, providing female companionship to the men away from home. For a fee she might also undertake cooking, laundry, or sewing. During a battle, she might distribute brandy and cartridges to the troops, and assist the wounded.

Usually from lower-class backgrounds, cantinières lived and travelled with a regiment and shared the same hardships as the soldiers.

Marriage

The Victorian army saw itself as a large family. Officers were encouraged to marry and to settle down; they played a paternal role within the regiment, and their wives an important maternal one.

Marriage for other ranks, however, was positively discouraged; a man’s regiment demanded his loyalty before a wife and child. A Victorian soldier needed permission from his commanding officer to get married, and this was only granted to a small percentage of the men in each regiment.

Fanny Duberly

The status of a 19th-century soldier’s wife was directly related to that of her husband. The wife of an officer would have shared her spouse’s privileges.

Frances Isabella 'Fanny' Duberly (1829-1903) was the wife of Captain Henry Duberly, paymaster of the 8th Hussars. She was one of few officers’ wives to accompany her husband throughout the entire Crimean War, and would be told about battles ahead of time so that she could watch from a good vantage point.

She was well loved by the troops, who nicknamed her 'Mrs Jubilee'. But her behaviour was considered unseemly by Victorian society. When she published her diary of the war in 1855, she wished to dedicate it to Queen Victoria. But the request was refused.

‘I rode up trembling, for now the excitement was over. My nerves began to shake, and I had been, although almost unconsciously, very ill myself all day. Past the scene of the morning we rode slowly; round us were dead and dying horses, numberless; and near me lay a Russian soldier, very still, upon his face. In a vineyard a little to my right a Turkish soldier was also stretched out dead.’Fanny Duberly describing the aftermath of the Charge of the Light Brigade — 1854

George Cadogan painted this image of a husband showing his wife where he will attack the next day, Sevastopol, c1855

The next day, Cadogan returned to the same spot, where the woman has found the body of her husband.

Lady Florentia Sale

Lady Florentia Sale (1790-1853), was the wife of Major-General Sir Robert Sale, the defender of Jalalabad during the First Afghan War (1839-42). She accompanied the British force on the 116-mile retreat from Kabul back to Jalalabad in 1842.

After witnessing much bloodshed and nursing the wounded, Lady Sale was eventually captured and imprisoned. After nine months' captivity she was finally released by Major-General Sir George Pollock’s army. She kept a diary during the retreat and her subsequent captivity, which was published to critical acclaim in 1843.

Dubbed the 'soldier's wife par excellence' by 'The Times', Lady Sale was also known as 'the Grenadier in Petticoats' by her husband's fellow officers.

‘I had fortunately, only one ball in my arm; three others passed through my poshteen near the shoulder without doing me any injury. The party that fired on us were not above fifty yards from us, and we owed our escape to urging our horses on as fast as they could go over a road where, at any other time, we should have walked our horses very slowly.’Lady Florentia Sale, 'A Journal of the First Afghan War' — 1843

The only wife I mean to be troubled with

While based in Burma in 1845, Lance-Corporal David Banham wrote home to a friend, describing the experiences of the soldiers whose wives had accompanied them on campaign: ‘I think of all the lives of misery in this world a married soldier’s is the worst.’

Yet, at the same time, he sang the praises of his own ‘wife’, writing:

‘She is a very faithful creature and is my constant companion sleeping or waking, like most women, she has a very long sharp tongue… She seldom speaks but when she does it is very effective being generally accompanied with something in the shape of an ounce of lead.’

He was, of course, not writing about a woman, but his musket!

‘Would to God my poor deluded countrywomen who are continually marrying soldiers could picture to themselves one half of the misery and degradation which must follow such a step… I have seen simple country girls turn out such low detestable characters under the name of soldiers’ wives, that I have often found myself upon the verge of cursing the whole sex.’Letter from Lance Corporal David Banham — 1845