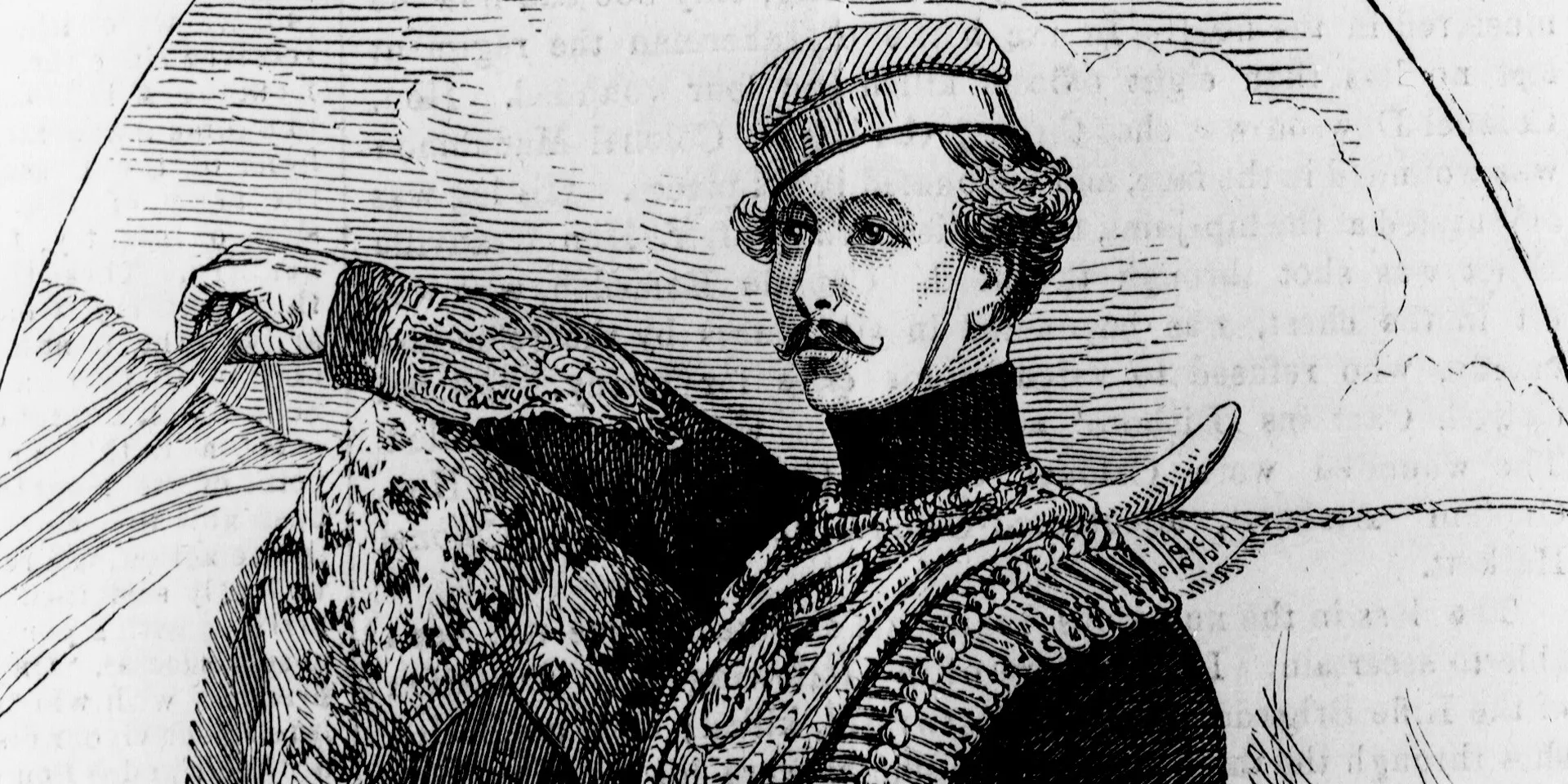

Captain Louis Edward Nolan, 15th Hussars

A rising cavalryman

Louis Nolan was born in Canada in 1818. The son of an infantry officer, his own military career began in 1832, when he joined the Austrian Army at the age of 14. In 1839, he obtained a commission in the 15th Hussars, a British Army cavalry regiment.

Nolan joined the 15th Hussars because the regiment was being sent to India. Owing to his father's influence, he was optimistic about his prospects for advancement there. However, like many British Army soldiers, he reacted badly to the climate and conditions on the subcontinent and had to return to Britain on extended sick leave in 1840.

He swiftly overcame this setback, securing promotion to lieutenant. He then took a training course that, in turn, enabled him to secure a position as a riding master at Bangalore on his return to India in December 1843.

While developing this equine specialism, Nolan wrote two books. The second of these, 'Cavalry: Its History and Tactics', reached a wide audience, helping him to establish a reputation as an authority on military horsemanship.

Crimean journal

In 1854, Britain and France joined the Ottoman Empire in its war against Russia. An Anglo-French force was despatched to Crimea. Its objective was to capture and destroy the Russian naval base at Sevastopol.

As Nolan appreciated, the Crimean War (1854-56) was a risky venture. Sevastopol was only captured after a lengthy siege and the British troops suffered severely in the winter of 1854 from lack of supplies and medical care.

Nolan enjoyed the good fortune of being made aide-de-camp to Brigadier General Richard Airey, the quartermaster-general of the British contingent. In this role, he was well placed to observe the events that unfolded.

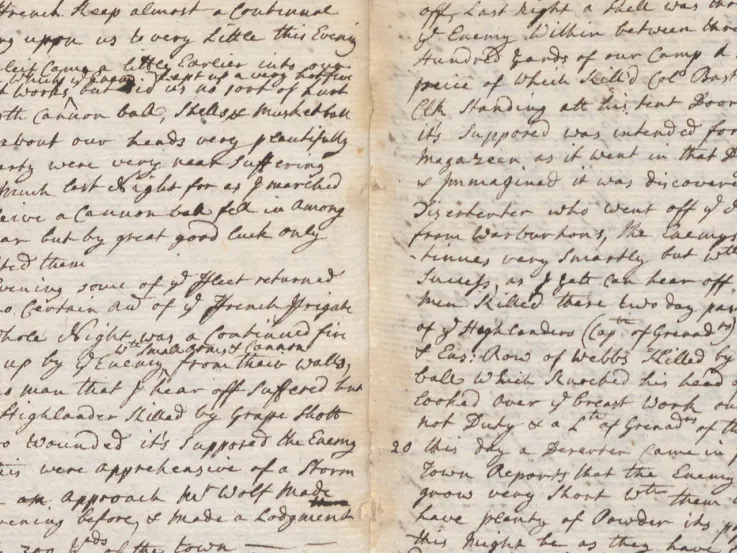

As the British force landed at Kalamita Bay on 14 September, Nolan began keeping a journal. From its style and format, it seems he was writing with an eye to publication. The entries for each day are divided into a ‘daily record’ and ‘remarks and additions’, indicating that he was keen to record a narrative of the campaign and to subject it to detailed analysis.

In keeping such a journal, Nolan was pioneering an important means by which an ambitious soldier could help make a name for himself and thereby advance his career.

‘The expedition to the Crimea was in a military point of view a gambling transaction in which all was staked on the turn of fortune.’Opening sentence of Louis Nolan’s Crimean War journal — 14 September 1854

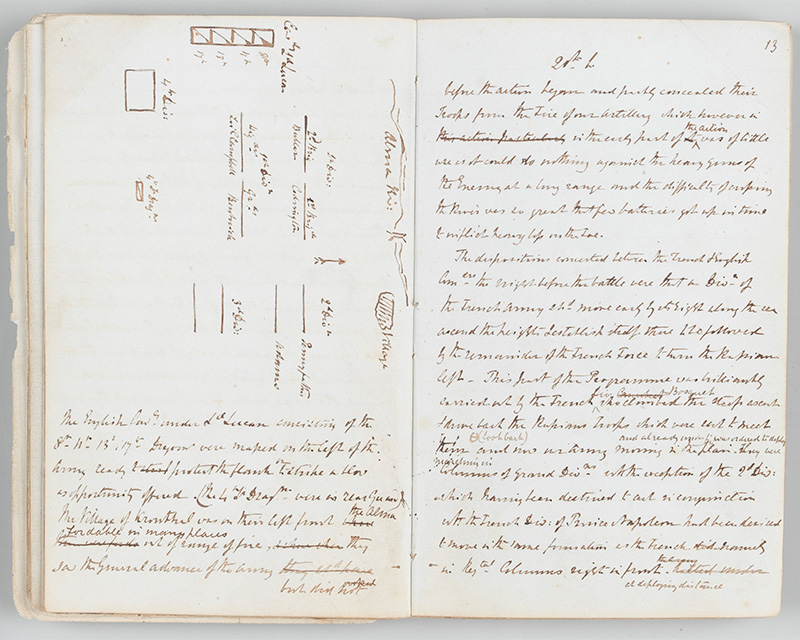

Battle of the Alma

Nolan’s journal is a valuable historical record of the early phase of the conflict. It notably includes a detailed account of the Battle of the Alma (20 September 1854), which has been used by many historians, in particular Alexander Kinglake - a contemporary of Nolan's - who wrote a multi-volume account of the war.

Named after the river over which the battle was fought, the Alma was the first engagement of the Crimean campaign. It saw the Anglo-French force successfully break through a Russian army that was attempting to block their advance upon Sevastopol.

As well as providing an accurate overall picture of the battle, Nolan enlivened his account with many incidents, and some gory details, which bring home the grim reality of the struggle.

‘A poor Russian Soldier in his shirt & drawers lay heavily wounded on the ground. I spoke to him – he rose on all fours & gradually rising on his knee he lifted up his shirt & showed me calmly that his bowels were all hanging out exposed by a canon shot.’Louis Nolan describing a gruesome encounter during the Battle of the Alma — 20 September 1854

The Charge of the Light Brigade

Perhaps of greater significance is the insight that the journal provides into Nolan’s attitudes and mindset. This helps us to understand the war’s most infamous episode, the Charge of the Light Brigade, an event in which Nolan was to play a pivotal role and in which he was to meet his death.

The Charge took place during the Battle of Balaklava (25 October 1854), a Russian offensive which aimed to break the siege of Sevastopol and cut the British off from their main supply port.

The battle started well for the Russians. They succeeded in capturing important ground, known as the Causeway Heights, from the Ottomans. However, they were subsequently halted and driven back by the British. The disciplined fire of the 93rd Highlanders - the famed ‘thin red streak tipped with a line of steel’ - and a charge mounted by the Cavalry Division’s Heavy Brigade both proved instrumental in this.

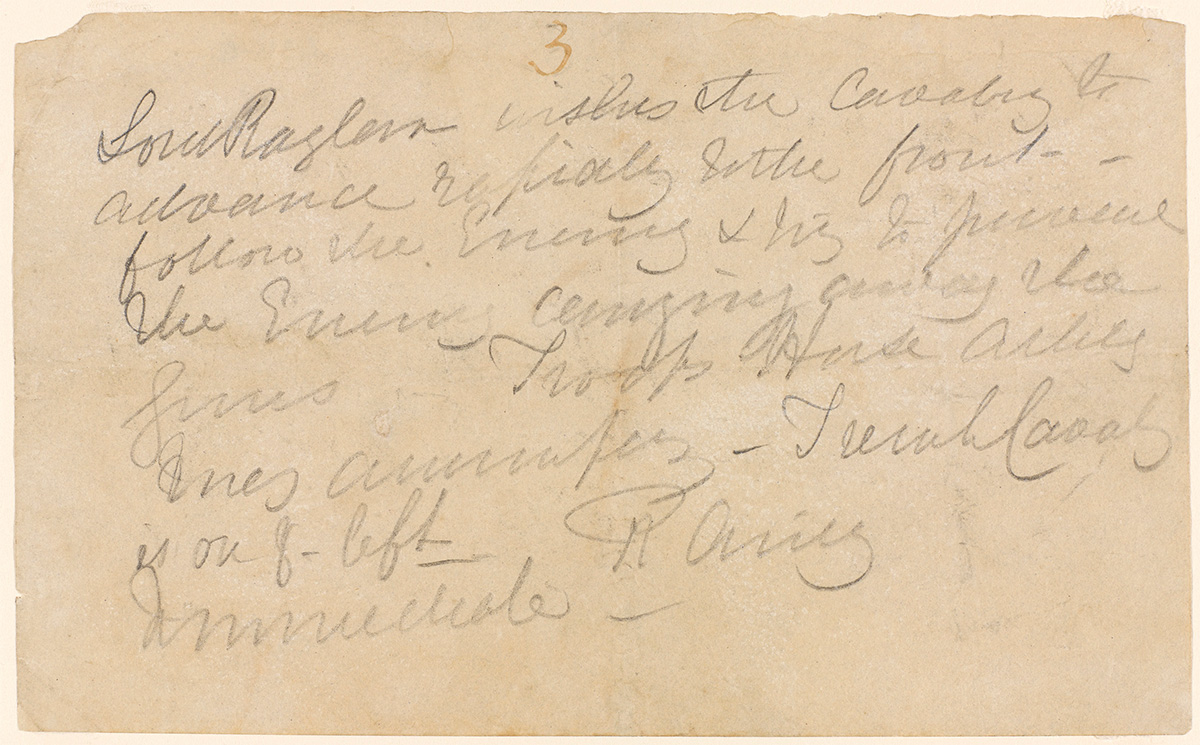

Botched communications

Eager to exploit this advantage, Lord Raglan, the British commander, ordered the Cavalry Division’s Light Brigade to advance towards the Causeway Heights to re-capture the ground lost by the Ottomans. However, his order was vague, and Lord Lucan, the commander of the Cavalry Division, felt the need to wait for clarification.

When Raglan saw the Russians hauling away British guns captured from the Ottomans, he sent a fresh order to Lucan to go and stop them. Nolan was the officer charged with delivering this fateful instruction.

From his position, Lucan couldn't see the guns that Raglan was referring to. Again, he hesitated and asked Nolan for clarification. At this, Nolan grew angry.

Gesticulating wildly, he declared: ‘There, my lord, is your enemy; there are your guns’. However, instead of indicating towards the Causeway Heights and the captured British guns, Nolan motioned instead to the massed battery of Russian guns at the north end of the plain’s north valley – a valley flanked by yet more Russian artillery.

The stage was now set for the tragedy that was to follow. Reluctant to resist such a direct order, Lucan ordered the Light Brigade to advance. Here, it met with disaster; 260 of its 673 men were killed, wounded or captured.

‘given without the slightest consideration, conveyed by a fool, and acted upon by a man too weak to decline attempting the impossible’The verdict of an officer of the Cavalry Division upon the order that launched the Charge of the Light Brigade — 19 December 1854

Blame game

This notorious episode provoked a heated and protracted argument over who was to blame. Nolan, the very first man to be killed as he dashed out at the head of charge, was unable to contribute to this debate. However, his journal does offer some valuable insights.

We know from the testimony of William Howard Russell, who was reporting on the war for 'The Times' newspaper, that his friend Nolan was angry and frustrated with Lucan for his cautious handling of the cavalry.

Nolan's journal provides further evidence of this attitude. Most strikingly, it records how Lucan had similarly failed to mount an attack during the Battle of the Alma, despite repeated orders to do so. Given this wider context, Nolan’s impatience can perhaps be more readily understood.

‘When a routed army was in full retreat what excuse can any one find for horsemen who did not do their duty and whose chief replied to an order to advance that the Russians were very numerous!!’Louis Nolan, criticising Lord Lucan’s handling of the cavalry at the Battle of the Alma — 20 September 1854

An unsolved mystery

However, a cloud of mystery continues to surround Nolan’s subsequent decision to gallop off, leading the Light Brigade into 'the valley of death'.

Was he overexcited at the prospect of glory? Was he determined to prove his theories on the potency of a cavalry attack? Or was this a desperate and futile attempt to make amends for a grievous error by attempting to steer the charge in the correct direction?

His journal offers no help here. And it's unlikely we will ever know for sure.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.