Gas attack on the Hohenzollern Redoubt at Loos, October 1915

Joint attack

On 25 September 1915 the Allies launched a new joint attack on the Western Front. The French went on the offensive in Champagne and Artois, while the British fought at Loos. The operation there saw the first major attack by the volunteer soldiers of the New Armies.

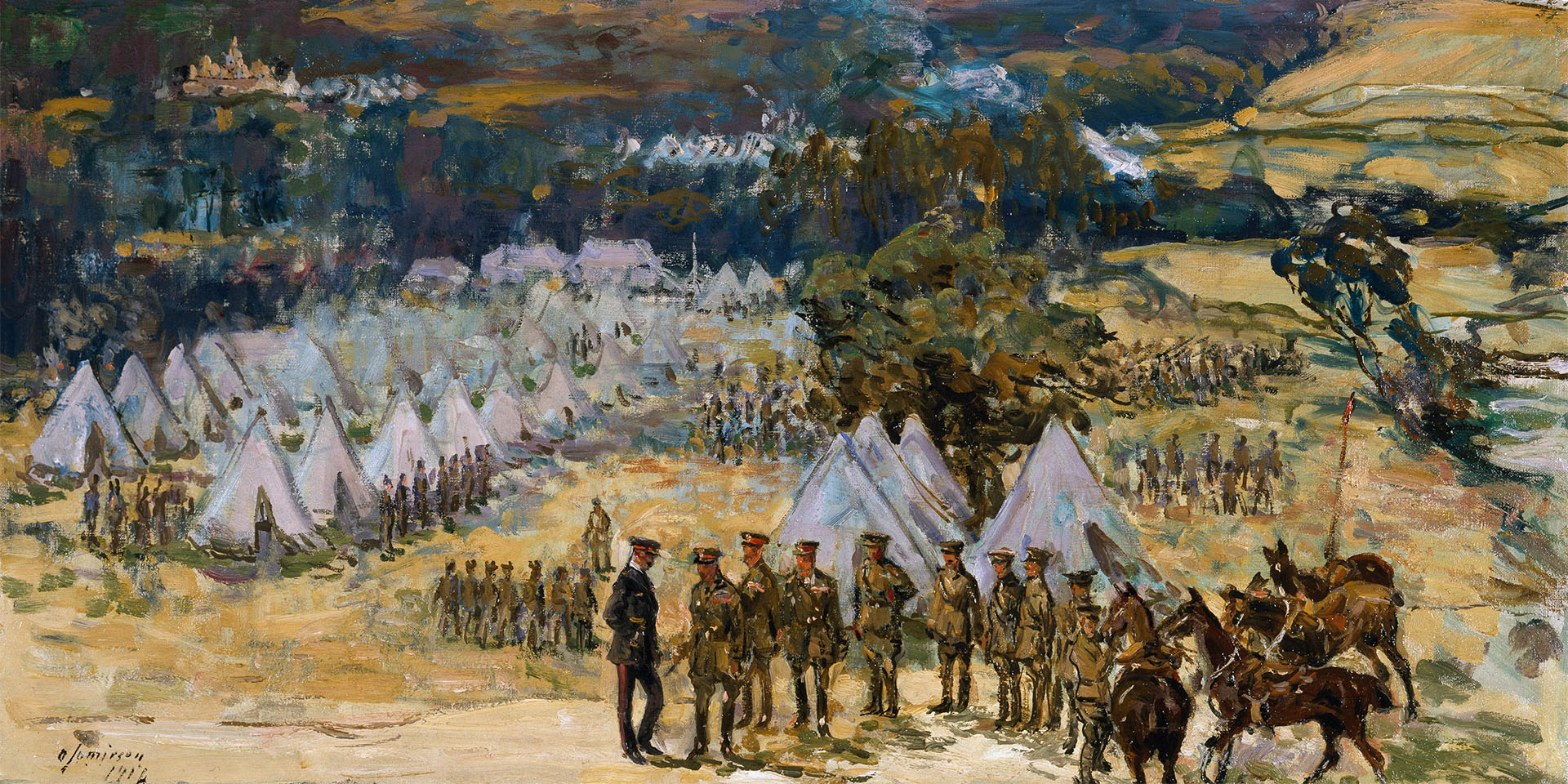

A New Army

Fresh troops - a combination of territorial soldiers, reservists and volunteers from Lord Kitchener’s New Army - began to arrive on the Western Front in 1915. Although enthusiastic, many had received very little training and were largely unprepared for trench warfare.

New weapon

Earlier in the war, the British had condemned Germany’s use of gas on the battlefield. But, in seeking a new way to break through, they decided to use chlorine gas for the first time to support their advance at Loos.

The gas was released from cylinders by special units from the Royal Engineers an hour before the infantry attacked.

Unfortunately, the weather proved fickle for the British and in some places the gas blew back into their trenches. In other parts of the line, the gas lingered in no-man’s land causing confusion.

'The gas hung in a thick pall over everything, and it was impossible to see more than ten yards. In vain I looked for my landmarks in the German line, to guide me to the right spot, but I could not see through the gas.'Letter from Second Lieutenant George Grossmith, 3rd Battalion The Leicestershire Regiment, to his fiancée — 27 September 1915

Battle

By the end of the first day, despite heavy casualties resulting from uncut wire, the troops had succeeded in breaking into the enemy positions near Loos and Hulluch.

Supply and communications problems, along with the late arrival of reinforcements, meant that the breakthrough could not be exploited over the following days.

The attacks ground to a halt and, by 28 September, the Germans had pushed the British back to their starting points.

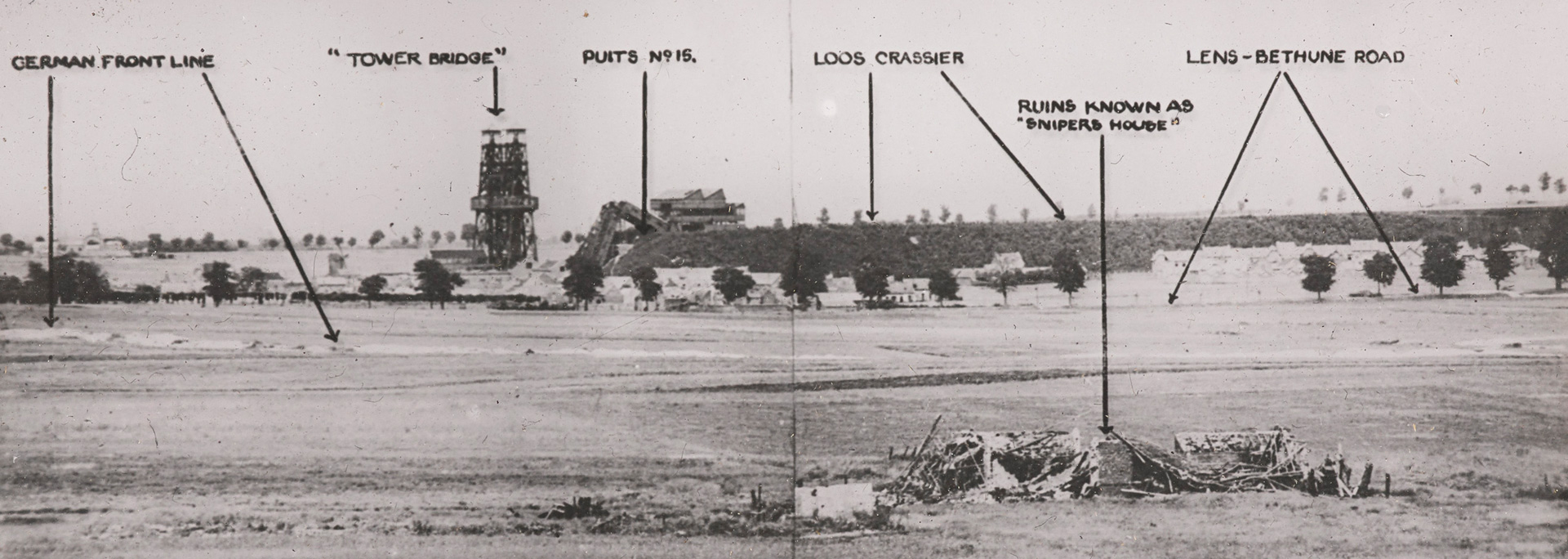

A panorama of a section of the Loos front taken on 30 September 1915

Aftermath

The offensive demonstrated that although it was possible to break into the German positions, it was not so easy to convert this kind of local success into a major breakthrough. It also showed that a much heavier artillery bombardment with more ammunition was needed. Likewise, better communication with reinforcements was essential.

The failures of the battle forced Field Marshal Sir John French to resign as commander of the British Expeditionary Force. He was replaced by General Sir Douglas Haig.

Cost

Around 2,600 British men were registered as casualties as a result of the failed gas attack, but very few of them died. Altogether, the British Army suffered over 50,000 casualties at Loos, almost double the number of German losses.

The author Rudyard Kipling’s son John was declared missing in action during the battle. His poem ‘My Boy Jack’, written shortly after, explores themes of loss. Devastated after searching for his son’s remains, he became an advocate of the Imperial War Graves Commission.

‘Have you news of my boy Jack? Not this tide. When d’you think that he’ll come back? Not with this wind blowing, and this tide.'‘My Boy Jack’, Rudyard Kipling — 1915

First World War in Focus

Explore our microsite, marking the centenary of the First World War. We uncover the national and global impact of the fighting, and tell the story of people from across the United Kingdom whose lives were affected by the conflict.