Sourcing horses

Until the 1880s, cavalry regiments were responsible for buying their own horses. In 1887, the Remount Department was created to take over this role. Animals were sourced from breeders, auctions and private families. Officers at this time still supplied their own horses.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, the Army had only 25,000 horses at its disposal. By the end of the conflict, it had purchased over 460,000 horses and mules from across Britain and Ireland, and even more from overseas.

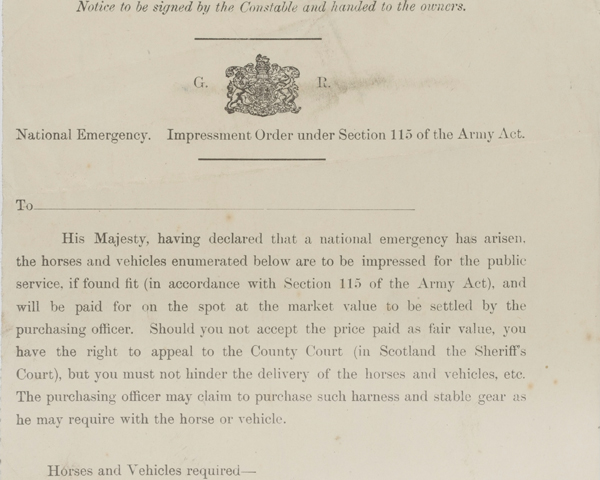

Requisition

Prior to the war, a census of British horses had been taken, identifying how many were available, how much they ate, and what type of work they were suitable for. Their nearest train station was also listed.

In the first few weeks of the conflict, the Army requisitioned around 120,000 horses from the civilian population. Owners who could not prove that their horses were needed for essential transport or agricultural duties had to surrender them.

Dr Reginal Hill worked for the Army Remount Department. He used the stationery box below on his travels around the country. It contains everything he needed to buy horses for the Army, including a chequebook, numerous official forms and labels, as well as a branding iron.

Overseas

The Remount Department also looked for help overseas, spending over £36 million (about £1.5 billion in today’s money) buying animals around the world, especially from America and Canada. More than 600,000 horses and mules were shipped from North America.

Travelling by sea was as dangerous for horses as it was for humans. Thousands of animals were lost, mainly from disease, shipwreck and injury caused by rolling vessels. In 1917, more than 94,000 horses were sent from North America to Europe and 3,300 were lost at sea. Around 2,700 of these horses died when submarines and other warships sank their vessels.

On 28 June 1915, the horse transport SS ‘Armenian’ was torpedoed by U-24 off the Cornish coast. Although the surviving crew were allowed to abandon ship, the vessel's cargo of 1,400 horses and mules were not so lucky and all perished.

Fever

Once on board the ships, the animals were placed in their stalls and given regular checks throughout the voyage. Despite the best efforts of the men who looked after them, many horses suffered from 'shipping fever', a form of pneumonia, and from various pulmonary complaints.

After their confinement, horses usually required several weeks to recuperate on landing. It was the job of the Remount Department and the Army Veterinary Corps to get them into shape and ready for active service.

Selection

Horses purchased for the Army had to meet certain criteria. A horse had to be over three years old, healthy and the right size for the work they were purchased to do - either for riding, for pulling guns or for transport.

The requisition of horses from civilians at the start of the war prompted some families to write to the War Office asking for their beloved family ponies to be spared. In response, the War Office decided that no horse under 15 hands high would be recruited. A horse's height was measured from its withers (the top of its shoulders) using a special stick.

The Remount Depot at Romsey, Hampshire, was kept busy day and night with shipments of horses from across Britain, as well as those arriving from overseas at nearby Southampton. All animals were checked for contagious diseases. Then, once passed for service, they were sent to the front.

Care

For hundreds of years, huge numbers of military horses had been lost through neglect. In 1796, the Army appointed veterinary officers to cavalry regiments to reduce the number of sick and injured horses lost on campaign.

The Blue Cross Fund, established in 1912, offered medical help and supplies to animals. This was especially important during the First World War as many new recruits had never worked with horses before and needed to learn quickly.

In 1915, the Blue Cross produced ‘The Drivers' and Gunners' Handbook to Management and Care of Horses and Harness’ to provide vital information for soldiers working with artillery, ambulance and supply horses.

‘All scurf should be removed from the mane, and the tail should be brushed well from behind.’The Drivers' and Gunners' Handbook to Management and Care of Horses and Harness — 1915

Grooming

In muddy conditions, it could take up to 12 hours to clean horses and their harnesses. But keeping horses well-groomed, even in the dirty conditions of the battlefield, served several purposes.

Practising good grooming standards meant that the horse was always prepared for battle at a moment’s notice. Grooming also helped to prevent chafing from harnesses and saddles, keeping horses in better condition for longer. At the same time, it gave the carers the opportunity to inspect their horses for pain, wounds or sickness on a daily basis.

Veterinary officers were told to clip their horses to help control skin infections like mange, which were prevalent in the boggy conditions of the Western Front. Unfortunately, this led to an increase in the number of animals dying from exposure to the cold and the mud. In 1918, the order was relaxed so that only the legs and stomachs were clipped.

Watering and feeding

A horse required ten times as much food as the average soldier. During the First World War, there was a distinct lack of grass for them eat on the Western Front or in the deserts of the Middle East. This meant that horse fodder was the largest commodity shipped to the front by many of the participating nations.

The demands on transport meant that feed had to be rationed. Of all the warring nations, British horses ate the best. The naval blockade forced the Germans to supplement their horses' feed with sawdust, causing many to starve.

The horses were fed from a nose bag rather than directly from the ground. This reduced waste and cut the risk of horses eating something that would make them ill. It also stopped a horse stealing another's food.

Farriery

Horses were expected to march long distances during wartime, sometimes up to 40 miles (64km) per day. Iron horseshoes wore out quickly, and usually had to be replaced every month.

Farriers and shoeing smiths were needed to keep horses moving. The primary job of a farrier was hoof trimming and fitting shoes to Army horses. This combined traditional blacksmith’s skills with some veterinarian knowledge about the physiology and care of horses’ feet.

Tools

Smiths usually carried the heavy materials they needed with them as they marched. An Army farrier would have used a variety of tools and nails to clean a horse’s feet and change its shoes.

Most farriers were non-commissioned officers; the majority served with artillery and cavalry regiments. One of their less welcome tasks was the humane despatch of wounded and sick horses.

Of the horses who died during the First World War, 75 per cent perished as a result of disease or exhaustion.

Even so, between 1914 and 1918, the Army treated its animals with greater care than ever before. Around 80 per cent of those treated by the Army Veterinary Corps were successfully returned to the front line.

Medical care

During the war, horses suffered greatly from cold temperatures, long marches and poor food. Equine diseases, respiratory problems and mud-borne infections were also prevalent, as were fatigue, exhaustion and lameness caused by work.

Combat injuries were not as common. But thousands of horses were still treated for bullet wounds, gas and even shell-shock.

Inspections

The primary aim of the Army’s veterinarians was to prevent disease and injury, both of which had caused huge losses in earlier conflicts. Horses were inspected daily by veterinary officers.

Many wounded animals were destroyed on the spot. But others were taken to casualty clearing stations for emergency treatment. Hospitals were established to treat the sick horses sent from the front, with equine ambulances and trailers developed to transport them there.

Equine medical care during the First World War was superior to in any previous conflicts. Between 1914 and 1918, the Army lost around 15 per cent of its horses annually. In comparison, 80 per cent were lost each year during the Crimean War (1854-56).

Picketing

Accommodating the huge number of horses on the front was a difficult task. There were not enough stables to provide shelter for every animal.

When the Army requisitioned new horses, they tried to prepare them for life outdoors by not stabling them before they were sent to the front. Instead, picket spikes were used to tether horses out in the open.

Usually, a number of spikes would be hammered into the ground and a rope strung through them. Then several horses could be tied to the rope. However, picketed horses were sometimes at risk of sinking in the sticky mud of the Western Front.

Humane despatch

Thousands of horses, mules, camels, donkeys and oxen were killed or wounded during the war. Others succumbed to fatigue and disease. While the Army Veterinary Corps tried to save as many as possible, a large number had to be destroyed.

The majority were shot, but specialist tools were sometimes used. The single-shot device pictured above unscrews to take a .310 cartridge. This was fired into the skull of the animal in order to despatch it as humanely as possible.