A nation of horses

Between 1811 and 1901, the number of horses in Britain grew from just over a million to more than 3 million. These animals were mighty draught horses, hard-working farm horses, racing thoroughbreds, old 'nags' and tiny Shetland ponies.

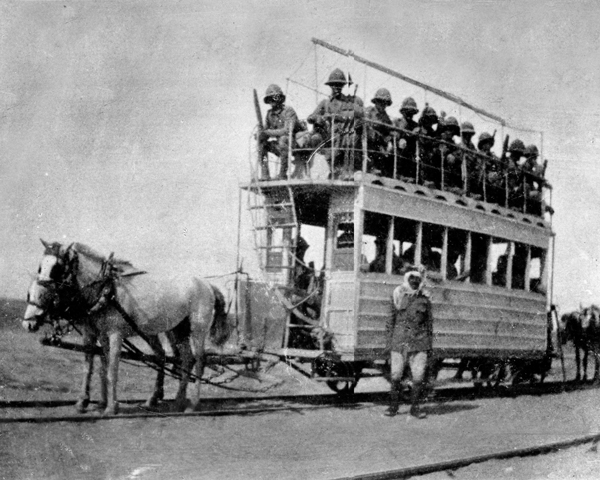

In the countryside they pulled ploughs and carts; in towns and cities they pulled omnibuses and cabs. Pit ponies hauled trucks of coal underground in mines. Horses were ridden in races and hunts, and for pleasure.

Horses required

At the outbreak of the First World War, the Army needed thousands of civilian horses to serve alongside its soldiers.

Different types were suited to different military roles. Riding horses were used in the cavalry and as officers’ mounts. Draught horses switched from pulling buses to hauling heavy artillery guns or supply wagons. Small but strong multi-purpose horses and ponies carried shells and ammunition.

By 1917, the Army employed over 368,000 horses on the Western Front. The vast majority of these were draught or pack animals rather than cavalry horses.

The Army’s Remount Department spent £67.5 million (about £3 billion in today’s money) purchasing, training and delivering horses and mules to the front. There were not enough horses in Britain that were fit for Army service, so large numbers had to be brought from abroad. Canada, for example, sent about 130,000 horses.

‘We consider the encouragement of the breeding of horses suitable for artillery and light draught to be of the utmost national importance, bearing in mind the fact that on mobilisation a larger quantity of these horses is required than of the riding type.’‘Report of the Committee on the Supply of Horses for Military Purposes’ — 1915

Supply line

Horses were part of a complex supply line. The British forces on the Western Front required a vast amount of ammunition, food and equipment.

The Army Service Corps was responsible for moving this material from the Channel ports, where it was collected in base depots. From there, supplies were moved by train to regulating stations, and then to either a railhead or advanced supply depot. For the final leg, they would be moved by horse, mule or motor transport to the quartermaster staff of front-line units.

Carrying

A horse can carry on its back only half the amount it can pull on a cart. However, unlike carts and other wheeled vehicles, horses and other pack animals can travel almost anywhere a soldier can go on foot.

On the Western Front, pack animals were often used to carry supplies to the front line, where roads had been destroyed by shelling or were swamped with mud.

Rough terrain

On the North-West Frontier of India and in East Africa, the nimble-footed mules of the Indian Army carried huge loads in mountainous terrain. This included special artillery guns that could be taken apart and transported by teams of eight mules.

During the Sinai and Palestine campaigns, horses, mules and camels were used to carry supplies and ammunition across rough desert terrain that was impassable to carts or motor vehicles. But casualty rates were high in the unforgiving desert terrain. In 1916, the Army lost an average of 640 horses a week.

Pulling

For thousands of years, people have been harnessing horses to wheeled vehicles to efficiently transport heavy loads over long distances. Their huge power and strength made horses a valuable resource for the Army.

The success of the British war effort was largely dependent on draught horses. Often, the mud on the Western Front was so thick, or the desert sand of the Middle East so deep, that motor vehicles could not drive through it. Instead, it was left to horses to deliver cart loads of supplies, medicine, food and ammunition.

Mobile guns

Horses also pulled artillery guns. For example, the main British artillery weapon of the war - the 18-pounder - could be quickly manoeuvred around the battlefield with a crew of ten men and six horses.

Ambulances

Pulling ambulances was one of the most important roles of draught horses. They could quickly transport injured soldiers from casualty clearing stations to field hospitals. Along badly shell-damaged roads, it would have been a very uncomfortable way to travel.

Timber

Horses also worked with the Forestry Corps, pulling felled logs and then moving cart loads of timber. Each forestry company had a team of 120 horses and there was great rivalry as to which team kept their horses in the best condition.

Wood was a vital resource for lining trenches and providing shelters for men and animals. It was used for the duckboards that enabled soldiers to cross the shell-scarred and muddy landscape. It was also used for railway sleepers on the narrow-gauge railways that transported troops and helped keep the Army supplied.

Dangers

Thousands of draught and pack animals succumbed to fatigue or diseases like mange. Others fell victim to the weapons of modern war.

The use of gas, artillery, mines, machine guns, mortars and tanks made the front a terrifying place for horses. In the early days of gas warfare, nose plugs were improvised for horses to help them survive. Later, special types of horse gas masks were developed.

Barbed wire was used in vast quantities to protect trenches. But thousands of horses got caught up in it and suffered severe injuries as they struggled to escape. Leg wounds suffered by horses often failed to heal or became infected, and the animals would have to be shot.

Peace

At the end of the war, the Army had far more horses than it needed in peacetime. Around 500,000 were sold for work, about 100,000 of these in Britain, the rest abroad.

Owing to public concern about the treatment of these animals, all buyers had to be investigated. The War Office promised that unwanted horses would be destroyed rather than sold on to cruel owners.

Sadly, around 61,000 horses that were unfit for work were sold for meat.