Enduring conflict

As geographical neighbours, Britain and Ireland have a closely entwined history. However, their relationship has often been characterised by conflict and enmity. This dates back to the Middle Ages, when England first laid claim to sovereignty over Ireland.

Since then, sectarian and ethnic divisions - originally stemming from the colonisation, or ‘plantation’, of Ireland by English and Scottish settlers in the 16th and 17th centuries - have greatly aggravated the situation. And the growth of a militant republican movement in Ireland from the 1790s onwards has served to perpetuate the struggle.

As a result, Ireland has been the arena for many battles and uprisings over the years. It has also has seen much civil unrest, some of which has spilled over to the rest of the British Isles.

1171

King Henry II arrives in Ireland

1542

King Henry VIII becomes King of Ireland

1594-1603

Tyrone’s Rebellion

1607

Flight of the Earls

1609

Plantation of Ulster

1641

Irish Rebellion of 1641

1642-53

Irish Confederate Wars

The Irish Catholic Confederation is formed in 1642 and attempts to take control of Ireland. This conflict merges with the British Civil Wars (1642-51) and draws in forces of the Royalists, the Parliamentarians and the Scottish Covenanters.

1649-53

Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland

The Confederate Wars culminate in the conquest of Ireland by leading Protestant Parliamentarian, Oliver Cromwell. This includes the storming of the towns of Drogheda and Wexford in 1649, during which the towns’ defenders are massacred. The conquest results in Cromwell’s soldiers and other settlers being given land confiscated from Catholics.

‘I am persuaded that this is a righteous judgement of God on these barbarous wretches, who have imbrued their hands with so much innocent blood; and that it will tend to prevent the effusion of blood for the future, which are satisfactory grounds for such actions which cannot otherwise but work remorse and regret.’Oliver Cromwell on the Drogheda massacre — 1649

Irish Army

From the reign of King Charles II (1660-85) until the Act of Union in 1801, regiments stationed in Ireland were maintained by Irish revenues. However, these soldiers remained completely under the control of the English Crown and at no time constituted a distinct army.

Established on a more formal basis in 1699, the Irish Army - also termed the ‘Army in Ireland’ or ‘Irish Establishment’ - had significant political implications. As well as alleviating the English tax burden, it reduced the size of the force that needed to be maintained in England, thus allaying the deep-seated fear of a standing army held by English parliamentarians since the Civil Wars (1642-51).

For most of this period, only Anglican Protestants were allowed to serve in the regular army. Catholics and Protestant non-conformists were prohibited from doing so. Between 1701 and 1756, a more extensive ban on the recruitment of Irishmen of any denomination into the rank and file was introduced. However, the demands for military manpower meant that, in practice, these prohibitions were often flouted.

1680

Royal Hospital Kilmainham is established

Kilmainham Hospital in Dublin is the first institution set up to care for Army veterans, representing a significant milestone in the development of soldiers’ welfare. Kilmainham also serves as a model for the Royal Hospital Chelsea, built in London shortly afterwards.

1684

The Royal Irish Regiment

Formed in Ireland by the Earl of Granard, this regiment is later ranked as the 18th Foot, before becoming The Royal Irish Regiment in 1881.

1685

4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards

Formed by the Earl of Arran to help suppress the Monmouth Rebellion, this cavalry unit serves on the Irish establishment from 1699 until 1788, subsequently becoming the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards.

1685-88

Protestant purge

During the short reign of the Catholic King James II (1685-88), the Army in Ireland is purged of many Protestant soldiers. As part of a wider transformation of the Army, this contributes to the outbreak of the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 in which James is overthrown by William of Orange, the leader of the Dutch United Provinces.

1689

New regiments raised to fight the Jacobites

Three new units - which later become the 27th (Inniskilling) Regiment of Foot, the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers and the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons - are raised in Ireland to serve against the deposed King James and his supporters, the Jacobites.

1689-91

Nine Years War in Ireland

To secure his place on the English throne, William confronts James and his supporters in Ireland. This renews the bitter internal struggle between Irish Catholics and Protestant settlers. James is defeated at the Battle of the Boyne (1690) and flees the country, never to return. His supporters fight on until their final defeat at Limerick the following year.

1691

Flight of the Wild Geese

Many Jacobite soldiers leave Ireland to take up service in continental European armies, most notably that of France. This forms part of a long tradition of Irish soldiers in exile. These soldiers are known as the ‘Wild Geese’.

1693

8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars raised

Raised in Ireland by Henry Conyngham, this cavalry unit becomes the 8th King’s Royal Irish Hussars in 1861.

1715

Militia Act

The Militia Act creates a new reserve force of infantry and cavalry, composed entirely of Protestants. This force is called out five times between 1719 and 1760 to meet threats from Jacobites and the French, but falls into decline after 1765.

1745

Battle of Fontenoy

Fontenoy bears witness to the most famous clash between the British Army and the 'Wild Geese' of France's Irish Brigade.

‘On Fontenoy, on Fontenoy, like eagles in the sun, With bloody plumes, the Irish stand - the field is fought and won!’Thomas Davis, from his poem 'Fontenoy 1745' — c1843

1778-93

Irish Volunteer Movement

Volunteer units are established to defend Ireland at a time when many regular troops are fighting in the American War of Independence (1775-83). These units are set up outside of government control and mark a major milestone in the development of Irish paramilitary forces. Perceived as a threat by the government in Ireland, the movement draws to an end in 1793.

1793

New regiments raised to fight Revolutionary France

Five new infantry units are raised in Ireland for the French Revolutionary Wars (1793-1802): the 83rd (County of Dublin) Regiment, the 86th (Royal County Down) Regiment, the 87th (Royal Irish Fusiliers) Regiment, the 88th Regiment (Connaught Rangers) and the 89th (Princess Victoria’s) Regiment.

1793

Militia Act

The Militia Act re-establishes a part-time force tasked with defending Ireland from both insurrection and invasion. While the act is initially met by widespread unrest, with many Irishmen resenting the idea of compulsory military service, the Militia forms an important part of Ireland’s defence force until the end of Napoleonic Wars in 1815.

1796

Irish Yeomanry established

The Yeomanry, a part-time cavalry force, is raised in reaction to the growing threat of insurrectionary groups like the Catholic Defenders and the Society of United Irishmen. Overwhelmingly Protestant, the Yeomanry is a deeply sectarian force, a factor which contributes to its disbandment in 1834.

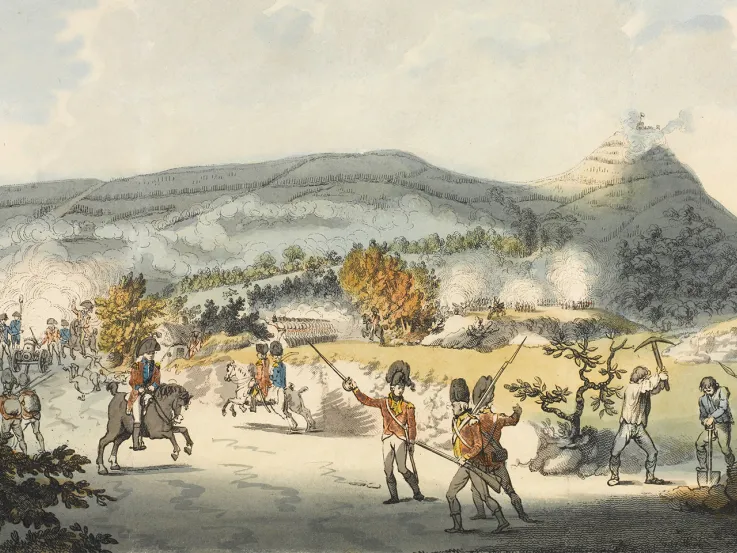

1798

Irish Rebellion of 1798

A rebellion against British rule in Ireland is instigated by the Society of United Irishmen. Despite French support, the rebels are totally defeated. But their actions inspire a new generation of Irish revolutionaries.

1801

Act of Union

Under the provisions of this act, Ireland becomes a formal part of the United Kingdom (UK). The act also brings the Irish military establishment to an end.

‘From my earliest youth I have regarded the connection between Ireland and Great Britain as the curse of the Irish nation, and felt convinced that while it lasted this country would never be free or happy.’Theobald Wolfe Tone, founding member of the Society of United Irishmen — 1798

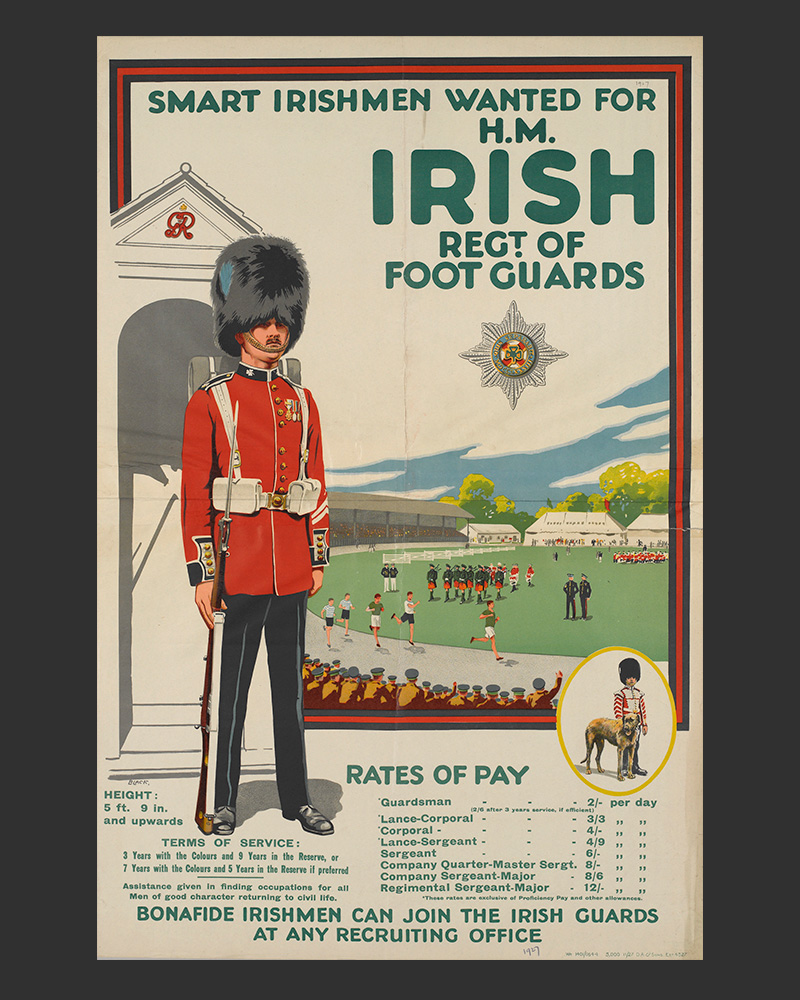

Largescale recruitment

At the end of the 18th century, the ban on Catholics serving in the Army was rescinded, leading to ever-larger numbers of Irishmen joining up. This trend was also driven by a combination of widespread poverty and Ireland's strong tradition of military service.

From the 1780s, around a third of Army recruits were Irish. Between the 1820s and 1860s, this rose to around 40 percent. They were drawn in particular to serve in the European regiments of Britain’s Indian Armies and played an important role in the building of the British Empire.

Their numbers declined towards the end of the 19th century, but the Irish remained well represented in the Army up to and including the First World War (1914-18).

1803

Robert Emmet’s Rebellion

Robert Emmet, the brother of the one of the leaders of 1798 Rebellion, instigates an uprising in Dublin. This attracts little support and is swiftly put down. Emmet is condemned to death, but his stirring speech in the dock serves to inspire future generations of Irish revolutionaries.

1848

Young Ireland Revolt

Inspired by revolutionary events across Europe, a group of Irish nationalists known as the ‘Young Irelanders’ launches a rebellion against British rule. This uprising attracts little support and is easily suppressed, but also serves to perpetuate the revolutionary tradition in Ireland.

1854

Irish Militia re-established

The outbreak of the Crimean War (1854-56) spurs the re-creation of the Irish Militia as a home defence force.

1858

Irish Republican Brotherhood founded

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) is founded in Ireland and the Fenian Brotherhood (later Clan na Gael) in the United States. Both are dedicated to overthrowing British rule in Ireland. They become known as the ‘Fenians’ after the warriors of Irish mythology, the Fianna.

1866-71

Fenian campaigns

The Fenians launch a series of abortive raids into Canada, hoping to hold the country hostage for Ireland’s independence. They also instigate an uprising in Ireland, which is similarly unsuccessful, and make efforts to infiltrate the British Army.

1881

Childers Reforms

As part of widespread Army reforms, eight new Irish regiments are formed through amalgamation or retitling: The Royal Irish Regiment, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers, The Royal Munster Fusiliers, The Connaught Rangers, The Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians), The Royal Irish Rifles, Princess Victoria’s (Royal Irish Fusiliers) and The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers.

1881-85

Fenian bombings

The Fenian movement fragments and declines during the last quarter of the 19th century, but a militant faction succeeds in instigating a terrorist bombing campaign in England and Scotland.

1899-1902

Boer War

Around 50,000 Irish soldiers serve with the British Army in South Africa during the Boer War. However, the conflict divides Irish society. Many are vocal in their support of the Boers and a small contingent of Irish troops join the Boers in the fight against Britain.

‘No man has a right to fix the boundary of the march of a nation; no man has a right to say to his country: “Thus far shalt thou go and no further.”’Charles Stewart Parnell, Irish nationalist politician — 1885

Social impact

Although its roles have often proved difficult and controversial, the Army has also performed an important social and economic function in Ireland.

For some, it has provided an opportunity for advancement. Many of the Army’s most celebrated commanders, including Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington, are of Irish descent. For many others, the Army has been a means of employment during times of hardship.

Irishmen have swelled the ranks of regiments across Britain and the Empire, not just those raised in Ireland. As a result, many Irish people continue to have strong personal ties to the Army through the service of their ancestors.

1900

Irish Guards formed

Formed by order of Queen Victoria in response to acts of gallantry by Irish units during the Boer War, the Irish Guards regiment continues to serve in the British Army today.

1901

South Irish Horse and North Irish Horse formed

Formed as part of a drive to build a large reserve of auxiliary cavalry units, the South of Ireland Imperial Yeomanry and the North of Ireland Imperial Yeomanry are retitled as the South Irish Horse and the North Irish Horse in 1908.

1908-09

Haldane Reforms

As part of an overhaul of the Army’s system of reserves, Irish militia units are disbanded and the rest are converted to Special Reserve units, where men have a duty to serve overseas in the event of war. In Britain, reserve units are merged into the newly formed Territorial Force. The only Territorial Force units raised in Ireland at this time are the Officer Training Corps formed in Belfast, Dublin and Cork.

1912

Irish Home Rule Bill introduced

After failed attempts in 1886 and 1893, a third Home Rule Bill is introduced by the British government, backed by the Irish Parliamentary Party. The bill aims to give Ireland devolved powers of government within the UK and so meet the growing clamour in Ireland for greater independence. The bill faces stiff opposition from unionists in Ulster. Passed into law in 1914, its implementation is postponed by the outbreak of the First World War.

1912-13

Irish paramilitary forces established

To resist home rule, Ulster unionists form a paramilitary force called the Ulster Volunteers. In response, Irish nationalists form a similar force known as the Irish Volunteers. Members of both groups go on to serve with the British Army during the First World War, but this militarisation plays a significant role in the outbreak of conflict in Ireland in 1916 and 1919.

1914

Curragh Incident

The British government contemplates using military force to implement home rule. Many British officers at the Curragh Camp - the Army’s main Irish base - are sympathetic to the cause of the Ulster unionists and threaten to resign rather than take any such action. Their resistance causes the government to withdraw and publicly disown the plans. This event is widely regarded as a mutiny, although no officers actually fail to carry out issued orders.

1914-18

First World War

Following the outbreak of war, Irishmen join the British Army in large numbers. Ultimately, around 200,000 – all of them volunteers - serve in the conflict and around 30,000 are killed. Hundreds of Irish women also volunteer, undertaking vital roles in the nursing services and the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

‘I joined the British Army because she stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilisation, and I would not have her (Britain) say that she defended us while we did nothing at home but pass resolutions.’Francis Ledwidge, Irish poet who served with the British Army in the First World War — 1917

1916

Easter Rising

The First World War provides an opportunity for militant nationalists to instigate a rebellion in Ireland in 1916.

1918

Conscription Crisis

To boost troop numbers on the Western Front, the British government attempts to extend military conscription to Ireland. This meets with hostility and serves only to strengthen the Irish republican movement.

1919-21

Irish War of Independence

Irish nationalist forces launch a bitter guerrilla war in Ireland. This results in independence for southern Ireland, which becomes the Irish Free State, and the creation of Northern Ireland, which remains within the UK.

1922

Disbandment of the Irish regiments

On the creation of the Irish Free State, the British Army disbands units that have traditionally recruited in southern Ireland: The Royal Irish Regiment, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers, The Royal Munster Fusiliers, The Connaught Rangers, The Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians) and The South Irish Horse. This event is marked by a formal ceremony at Windsor Castle on 12 June, where the regimental colours are laid up.

‘I fully realise with what grief you relinquish these dearly-prized emblems; and I pledge my word that within these ancient and historic walls your colours will be treasured, honoured, and protected as hallowed memorials of the glorious deeds of brave and loyal regiments.’King George V, during the ceremony at Windsor Castle for the laying up of the colours of the disbanded Irish regiments — 1922

1922

5th Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards formed

Formed by the amalgamation of The Inniskillings (6th Dragoons) and the 5th Dragoon Guards (Princess Charlotte of Wales's).

1938

Territorial units raised in Northern Ireland

Territorial Army units - including an all-female Auxiliary Territorial Service detachment - are raised in Northern Ireland for the first time.

1949

Ireland becomes a republic

The Republic of Ireland Act comes into force, ending all remaining ties between the state of Ireland and the British monarchy.

1958

The Queen’s Royal Irish Hussars formed

Formed by amalgamating the 4th Queen's Own Hussars and the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars.

1968

Royal Irish Rangers formed

Formed by amalgamating three Northern Irish regiments: The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, The Royal Irish Fusiliers (Princess Victoria’s) and The Royal Ulster Rifles.

1969-2007

‘The Troubles’

The suppression of protests challenging anti-Catholic discrimination ignites a long period of unrest in Northern Ireland. Terrorist attacks extend to the Republic of Ireland, the British mainland and beyond. Co-operation between British and Irish politicians eventually results in the signing of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, bringing an end to most of the violence.

1970

The Ulster Defence Regiment formed

Formed in the early years of 'The Troubles' to take over military duties from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) in Northern Ireland.

1992

The Royal Irish Regiment formed

Formed from the amalgamation of The Royal Irish Rangers and The Ulster Defence Regiment, this unit has no connections with the original Royal Irish Regiment raised in 1684.

A proud heritage

Irish soldiers have served in every corner of the globe and in many of the Army’s most arduous campaigns. Over the course of this service, they have established an illustrious fighting reputation.

Some of the Army’s most decorated soldiers are from Ireland. The country has also produced some of the Army’s most iconic characters, such as Lieutenant Colonel Blair ‘Paddy’ Mayne of the Special Air Service.

This proud tradition continues through the current-day Irish regiments: the Irish Guards and the Royal Irish Regiment. At the same time, careers in all areas of the British Army are open to citizens of the Republic of Ireland. Consequently, Irish soldiers still have a strong presence in today's Army, and Irish heritage remains integral to the Army’s character.