An age-old conflict

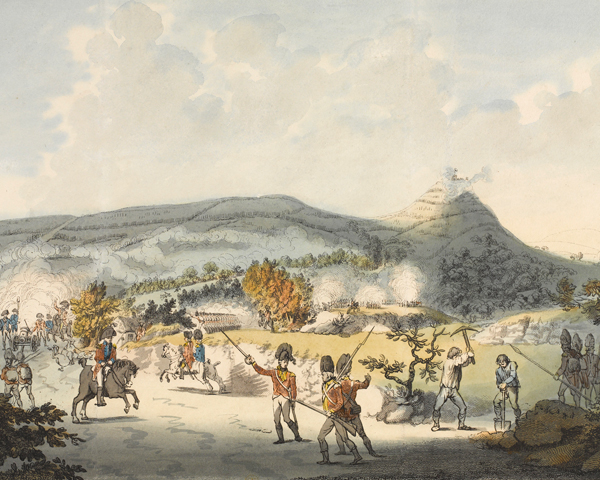

The Irish War of Independence, or Anglo-Irish War, was the climax of a centuries-long struggle for control of Ireland that had seen many bloody wars and revolts against English (and then British) rule, including the Rebellion of 1798.

Over the years, this had taken the form of both a sectarian battle between Catholics and Protestants, concentrated mainly in the northern province of Ulster, and a parallel conflict between Irish republicans and the British government.

Spirit of rebellion

Unresolved frustrations served to foster and perpetuate a spirit of rebellion and a tradition of secret oath-bound organisations. The most significant to emerge in the 19th century was the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

Founded in 1858, the IRB was responsible for a campaign of violence that ran from the 1860s to the 1880s. It would also play a crucial role in the outbreak of both the Easter Rising of 1916 and the War of Independence in 1919.

Home Rule

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a revival of Gaelic culture in Ireland infused the minds of a new generation with a deeper sense of national pride and identity. Along with new democratic ideas and growing calls for land reform, this helped engender a passionate commitment to the cause of Irish independence.

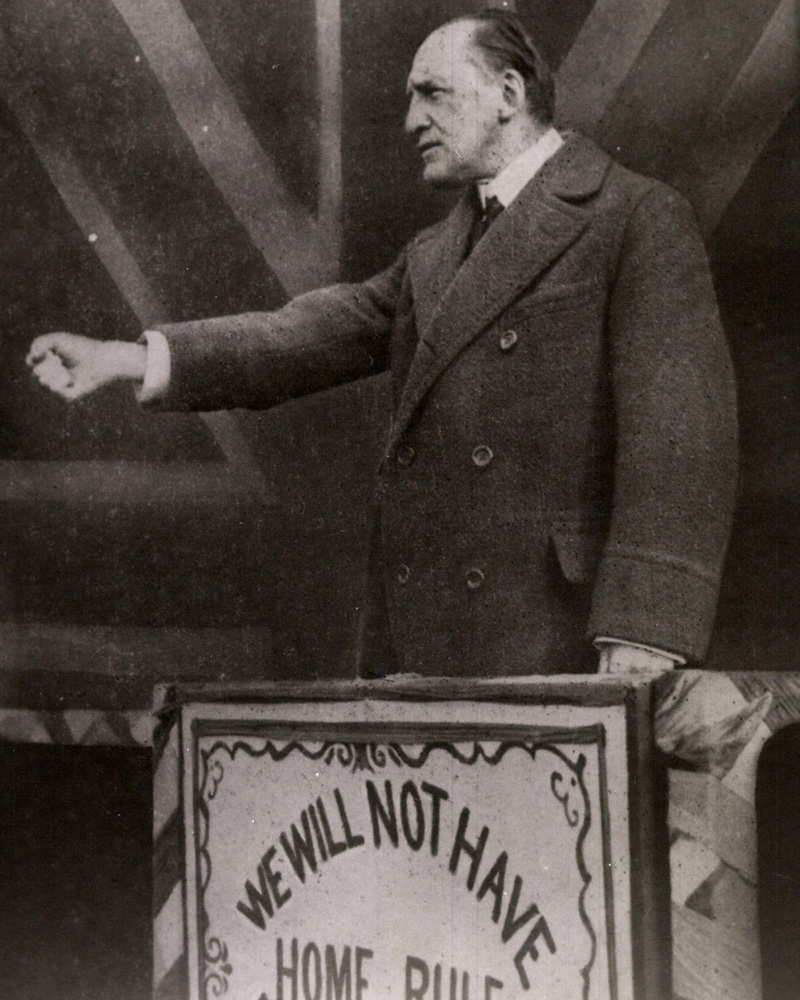

This period also saw a movement spearheaded by the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) to achieve devolution for Ireland by peaceful and constitutional means. After two parliamentary defeats in 1886 and 1893, this policy - known as ‘Home Rule’ - eventually reached the brink of success in 1912 and was set to become law in 1914. However, it still faced fierce opposition in Ulster, where the Protestant majority was reluctant to be placed under Catholic rule.

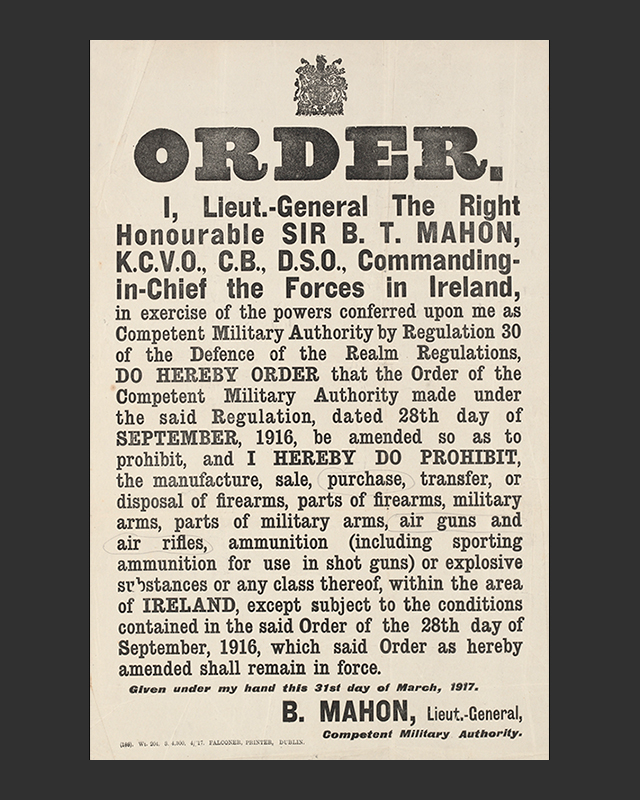

Rifle smuggled into Ireland by the Ulster Volunteers, 1914

Paramilitaries

Determined to resist Home Rule by any means necessary, the Ulster unionists, led by Edward Carson and James Craig, formed a paramilitary unit called the Ulster Volunteer Force.

In response, Irish nationalists established the Irish Volunteer Force. This rival unit allied itself with the Dublin-based Irish Citizen Army, a republican socialist working-class body already formed during a wave of industrial disputes in the city.

All of these groups sought to smuggle arms into Ireland and become proficient in their use. This militarisation further exacerbated political tensions and was an ominous milestone on the road to open conflict.

The Curragh Incident

Home Rule also faced opposition within the British military. In March 1914, many officers at the Army’s main Irish base, the Curragh Camp in County Kildare, threatened to resign rather than risk being ordered to use force to coerce the Ulster unionists. In the face of this resistance, the government was compelled to backtrack and disown any such plans.

The strength of feeling that drove these officers to take such drastic, practically mutinous, action is revealed in an account by Lieutenant Colonel Maurice MacEwen of the 16th (The Queen’s) Lancers. MacEwen was one of the most senior officers to resign and was one of three who were recalled to London to account for their decision at the War Office.

To their surprise, they found a sympathetic reception and obtained a guarantee which enabled them to rescind their resignations and re-join their units. Indeed, many senior officers in London had privately encouraged the disobedience of MacEwen and his fellow officers.

‘It seemed a hard bargain to place our commissions and pensions against the coercion of Ulster, but we had all jumped at it, and had the bargain been much harder we should still have jumped at it.’Lieutenant Colonel Maurice MacEwen — 1914

First World War

The outbreak of the First World War in August 1914 temporarily diffused the brewing crisis. The Home Rule bill passed into law in September. However, it was suspended for the duration of the conflict with the question of whether there would be separate treatment for Ulster unresolved.

These were bitter blows to the constitutional nationalists of the IPP. But their leader, John Redmond, still encouraged his followers to support the war effort by joining the British Army.

This caused a split in the Irish Volunteers. The majority - around 170,000 men - sided with Redmond, adopting the new title of National Volunteers. Of these, around 30,000 heeded his call to enlist. A more militant minority of around 10,000 were hostile to the war. They chose to break away, but retained the name Irish Volunteers.

Redmond's call to support the war was matched by the Ulster unionists, with both sides keen to prove their loyalty and bolster the moral case for their respective causes. Altogether, around 200,000 Irishmen joined up. Around 30,000 were to lose their lives in the fighting.

Easter Rising

The setbacks to Home Rule cultivated a sense of betrayal that would help the IRB both to justify an uprising and assemble an armed militia to instigate it, drawn from the Irish Citizen Army and those Irish Volunteers who had refused to join the British war effort.

Operating on the old adage that ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’, they used the First World War as a chance to strike.

Remembered as the Easter Rising, the IRB’s rebellion was launched on Easter Monday 1916 and ended in bloody failure. However, British handling of the defeated rebels served to transform Irish politics, creating a wave of popular nationalist and republican sympathy. This was fuelled further by a botched British attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland in 1918, a move which alienated many Irishmen.

This shift in attitude propelled Sinn Féin (‘we ourselves’), a hard-line nationalist party with connections to the IRB, to victory in the election of 1918.

Dáil Éireann

To achieve their goal of an independent Ireland, Sinn Féin sought to unilaterally break away from Britain. The newly-elected representatives refused to take up their seats in Westminster. Instead, on 21 January 1919, they assembled the first Irish Assembly, the Dáil Éireann, in Dublin.

The Dáil issued a declaration of independence and appealed for international recognition. It also sought to build new machinery of government that would subvert British authority across Ireland and encouraged passive resistance, such as strikes and boycotts.

Outbreak

While the Dáil’s position was certain to provoke a hostile response from Britain, its members were divided on whether violence should be employed to achieve their goal. However, by now, the IRB and the Irish Volunteers were propelling the country towards war.

On the same day the Dáil first assembled, two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) were killed in Soloheadbeg in County Tipperary. This action marked the outbreak of the War of Independence.

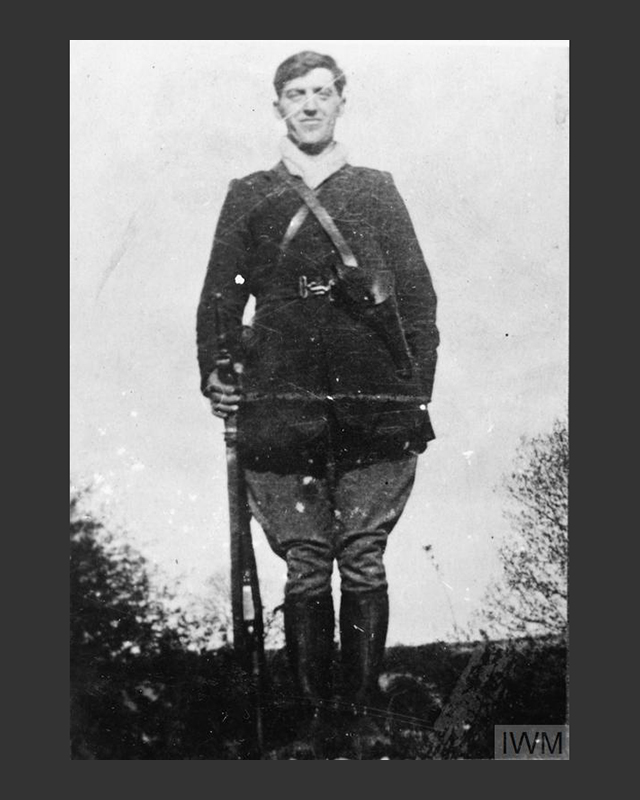

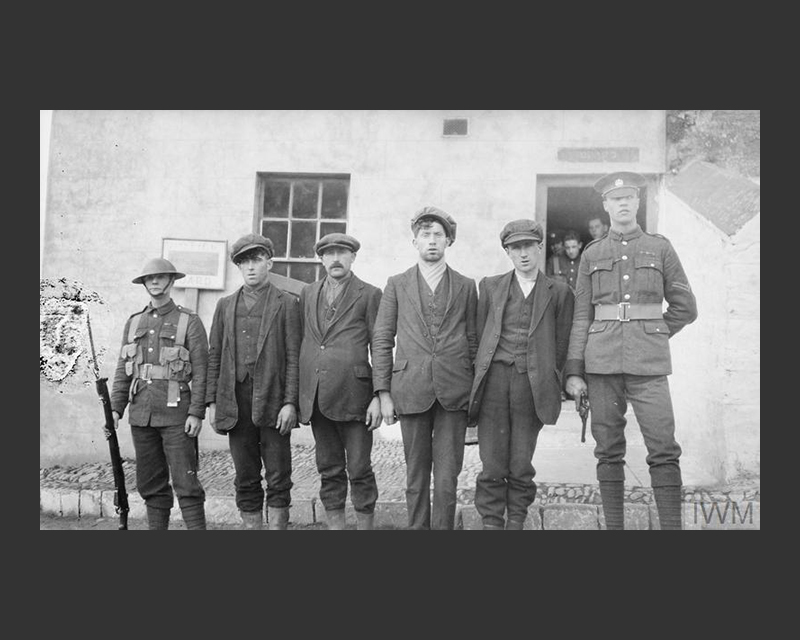

A member of the IRA, c1920 (© IWM Q 107791)

Irish Republican Army

The IRB and Irish Volunteers were soon operating under a new name, the Irish Republican Army (IRA). With only a few thousand men in the field at any time, and desperately short of arms and ammunition, they could not risk the kind of open warfare attempted in 1916. Instead, they resorted to guerrilla tactics of hit and run.

They organised their forces at a local level into small and highly independent groups. These units undertook ambushes and assassinations, and struck at key infrastructure - police barracks, tax offices, lines of communication - relying on the support of local people to help them evade capture.

Their principal target was the RIC, the most important symbol and instrument of British rule in Ireland, and the most readily accessible source of badly needed arms.

Early operations

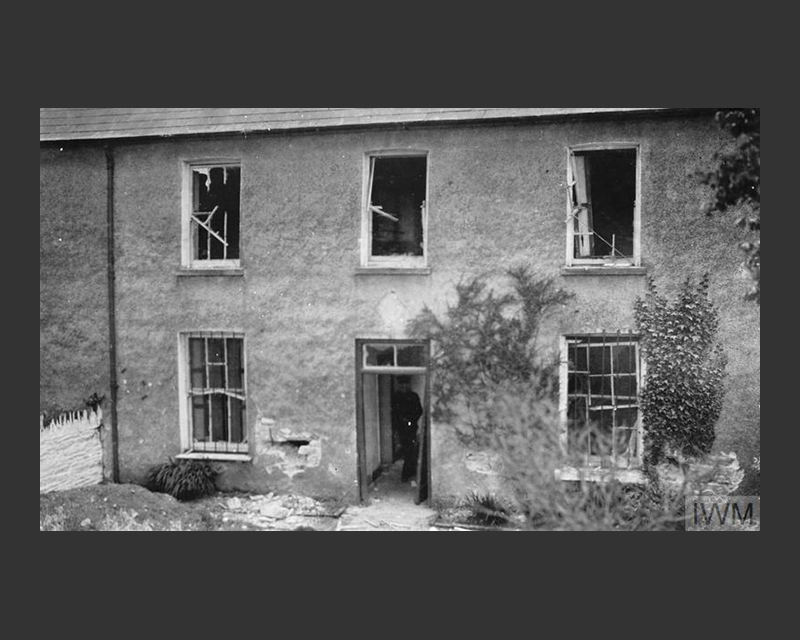

Events moved slowly. In the opening months of the war, violence was only sporadic and casualties were few. However, the conflict began to intensify towards the end of 1919, when the IRA launched a series of attacks on RIC barracks across southern Ireland.

By early 1920, many barracks had been destroyed and many more had been evacuated. This was an important victory for the IRA, effectively removing British authority from large swathes of the country.

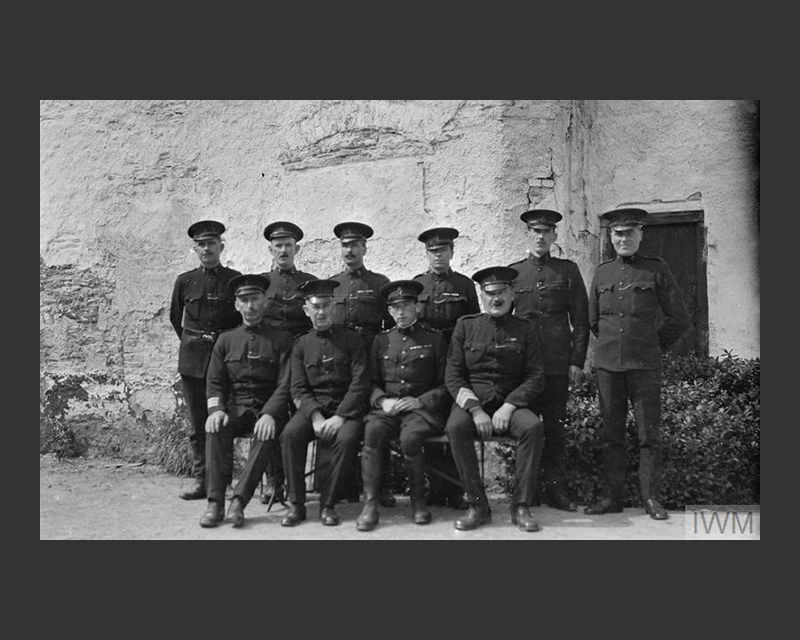

Men of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), 1920 (© IWM Q 71729)

The RIC barracks at Belgooly, blown up by the IRA, 1920 (© IWM Q 71701)

Propaganda

Despite this success, the IRA was never likely to win an outright military victory over the British. As a result, their strategy took on a propaganda dimension, exploiting newspaper coverage of the reprisals meted out by British forces in response to IRA attacks.

The goal was to consolidate their local support, while also undermining British support for the conflict and diminishing Britain’s reputation on the world stage.

‘No war can be carried on effectively in the full glare of public criticism.’Sir John Anderson, Under-Secretary for Ireland — 1920

Intelligence

In previous revolts, British intelligence had been a key instrument of victory, enabling the infiltration and undermining of Irish rebel groups. However, it had been in decline and the IRA now held the upper hand in this area.

Central to the IRA's success was Michael Collins, their Director of Intelligence and most formidable military commander. Collins cultivated a wide network of spies and even succeeded in penetrating the police and Dublin Castle, the seat of British power in Ireland.

He also assembled an elite group of agents known as the ‘Squad’ to conduct targeted killings. In 1919, they gained notable success eliminating detectives of the Dublin Metropolitan Police and, in December, almost assassinating Field Marshal Lord French, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

The car in which Lord French was ambushed, 1919 (National Library of Ireland (HOGW 125))

British response

As the British government gradually became aware of the deteriorating situation in Ireland, it introduced the Government of Ireland Act 1920 in the hope of bringing about a political settlement. However, this new legislation fell far short of what would now satisfy the demands of most Irish nationalists, granting only the limited freedom of Home Rule rather than full independence and republican status.

Moreover, it inflamed nationalist feeling by making provision for the formal division of Ireland, with a separate administration for the six mainly Protestant counties of Ulster.

The inadequacy of the British government’s political response was mirrored by its failure to address the violence on the ground. Reluctant to admit to a state of war, the British sought to combat the IRA using the police, with the Army assigned only a supporting role.

Still, it was appreciated that the RIC would need to be bolstered by additional equipment, units, and powers. Furthermore, the British now realised they would also need to rebuild their intelligence capability to close the net on their enemies.

Muddled strategy

In 1920, the British brought in new men to improve both the governance of Ireland and the conduct of operations.

General Sir Nevil Macready, the new army commander, was widely respected, with experience of command in the London Metropolitan Police and in Ireland. He appreciated that military power could only bring temporary restoration of British fortunes and that a deal granting independence was the only viable course of action. Other figures, like Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Tudor, the new police advisor, took a more hawkish line.

These differences led to a muddled strategy. The government ultimately allowed the military response to escalate steadily in an attempt to win victory, but never really committed the powers and resources required to completely achieve this objective.

‘Coercion has been tried in the past and has failed. Will the situation be any worse in the future if a policy of giving the people the fullest measure of self-determination within the Empire is tried?’General Sir Nevil Macready — 1920

Black and Tans

To fight back against the IRA, the British greatly expanded the RIC. They first recruited a large contingent of constables, comprised mainly of ex-soldiers, known as the ‘Black and Tans’ owing to their mis-matched uniforms.

A new paramilitary force, the ‘Auxiliary Division’ (AD), was also established. Formed of ex-officers, the AD was intended as a mobile elite striking force.

These units were given little training and were deployed with neither clear objectives nor an adequate system of hierarchical control. Consequently, they swiftly acquired a reputation for ill-discipline.

Black and Tans and Auxiliaries outside the North and Western Hotel, Dublin, 1921 (National Library of Ireland (HOGW 117))

Reprisals

Embittered by IRA killings, and frustrated by their inability to get to grips with their elusive foe, the men of these units were responsible for many atrocities. These included torture, extra-judicial killings and the burning of houses and businesses of nationalist sympathisers.

While unofficial, these actions were undertaken with the tacit approval of the British authorities. However, they proved to be entirely self-defeating. Not only did they fail to crush or cow their enemies, they also gave substance to the propaganda campaign waged to discredit the British in the eyes of the world.

‘The truth is that these reprisals are more or less winked at by the Government.’Maurice Hankey, Cabinet Secretary — 1920

Escalation

By the second half of 1920, the war had intensified. Violence had now spread across Ireland, but was most prevalent in Dublin and the south-west province of Munster.

The Army’s role had steadily grown. Units were now more heavily engaged in assisting the police, and Army barracks had increasingly become the targets of IRA attacks.

Under mounting pressure, the IRA had adapted their tactics. Small units were now formed into highly mobile ‘flying columns’ to conduct ambushes and facilitate rapid escapes.

Growing violence

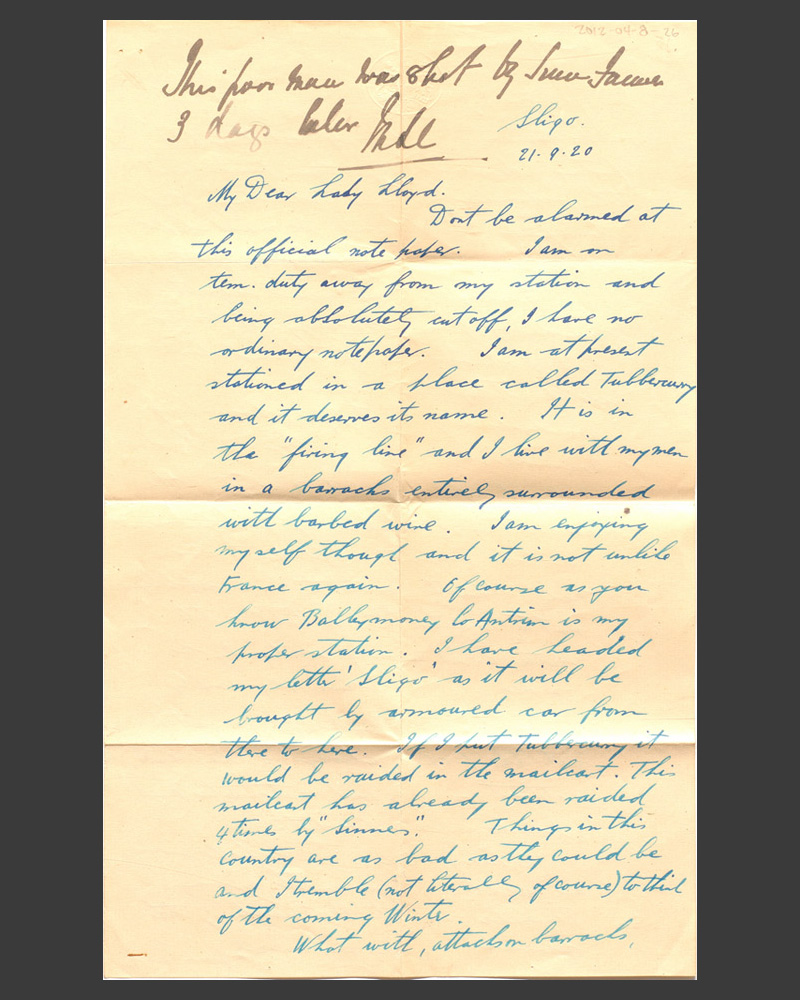

An insight into this growing violence is revealed in a letter by District Inspector James Brady of the RIC. Brady had served in the Irish Guards during the First World War. On his demobilisation from the Army, he joined the RIC, just as the War of Independence was beginning.

While serving at Tubbercurry (County Sligo) in September 1920, he was fearful of the deteriorating situation, writing: ‘Things in this country are as bad as they could be and I tremble... to think of the coming winter.’

Brady's forebodings proved well-justified. He was killed in an IRA ambush nine days later, a day before he was due to be relieved.

‘What with attacks on barracks, raids for arms, cutting off girls’ hair and shooting individuals by Sinn Féiners and then reprisals and shootings and burnings, there won’t to be much left of this wretched island shortly.’District Inspector James Brady, Royal Irish Constabulary — 21 September 1920

Climax

The spiralling violence resulted in rising casualties and the destruction of many towns and cities, including Tuam (County Galway), Limerick, Balbriggan (County Dublin) and Cork. However, the most notorious incidents took place on a day remembered as ‘Bloody Sunday’.

On 21 November 1920, Collins’s squad successfully targeted 20 military intelligence officers in the city of Dublin. Fourteen were killed and six were wounded. That afternoon, a massacre ensued at Croke Park football ground, where a group of Auxiliaries fired indiscriminately into the crowd, killing 14 and wounding over 60.

In the wake of these events, the British declared martial law across parts of south-west Ireland and sanctioned a programme of official reprisals. The Army was also given a greater role, mounting sweeps across the countryside to systematically hunt down the insurgents.

In response, IRA attacks become more ruthless and widespread. The first half of 1921 saw the conflict reach its bloody climax.

The Burning of Cork, 1920 (National Library of Ireland (HOGW 153))

The death of Michael O’Shea

The brutal and chaotic nature of the fighting at this time is demonstrated in the story of Second Lieutenant Michael O’Shea of the ‘H’ (Granagh) Company, 4th Battalion, West Limerick Brigade, IRA.

In May 1921, a former British soldier was found guilty of spying by an IRA court near Ballinleena (County Limerick). In the increasingly tense and bitter climate, such prisoners could expect no mercy and he was sentenced to death.

O’Shea was tasked with escorting the man to a place of execution. While passing along the Ballinleena to Bruree road, his unit stumbled into a British patrol. Mistakenly identifying them as a party of their own men, they failed to halt and the British opened fire. O’Shea was mortally wounded and the prisoner escaped.

Ulster

The war also had a profound effect on the province of Ulster. Here, unionist leaders accepted the proposal to divide Ireland, seeing this as the best means of preserving their place in the United Kingdom. To bring this about, they pressured the government to devolve control of the machinery of government and established their own security force, the Ulster Special Constabulary.

Nationalists, for whom a united Ireland remained a key objective, resented this outcome. However, the IRA had only a limited capacity to take the fight into Ulster, with their freedom to operate curtailed by the largely hostile local population.

The IRA still made many targeted attacks on security personnel in Ulster, inducing the inevitable tit-for-tat reprisals. Ulster also saw much sectarian violence in the form of riots, civil unrest and people driven from their homes. The conflict here also merged with industrial disputes, most notably when thousands of Catholics were expelled from the Belfast shipyards.

Violence would continue in Ulster long after peace had returned in the south.

IRA suspects guarded by British soldiers at the Bandon Barracks, July 1920 (© IWM Q 71708)

Peace

The growing British military and police effort in 1921 began to take a heavy toll on the IRA. Many of its men had been arrested and they remained desperately short of arms and ammunition. At the same time, the British were facing growing pressure at home to bring the conflict to an end and victory was still nowhere in sight.

A truce was negotiated in July 1921, followed by the signing of a treaty on 6 December, which brought the conflict to a formal end. The following year, all British forces were withdrawn from southern Ireland.

The war had cost around 1,400 lives, including more than 600 members of the British security forces and over 700 civilians and members of the IRA.

Legacy

The peace treaty finally achieved the core nationalist aim of creating a self-governing Ireland, which came into existence in 1922 as the Irish Free State. However, it fell short of delivering full republic status, which many felt was their goal. It also resulted in the country's partition, with six counties of Ulster forming Northern Ireland and remaining part of the United Kingdom.

The disagreements immediately plunged the Free State into a bitter civil war between those who supported the treaty and those who opposed it. This conflict witnessed the assassination of Michael Collins, the man held responsible for the agreed terms, but ultimately ended in victory for the pro-treaty side.

Over the following decades, the Irish Free State made further strides towards full independence, eventually becoming the Republic of Ireland in 1949. However, tensions and difficulties resulting from partition continued to beset the British Isles.

A further era of civil strife, sectarian violence and terrorism, known as 'The Troubles', erupted in 1969 and endured for decades. The Good Friday Agreement of 1998 brought an end to much of the violence, but the political differences continue to this day.