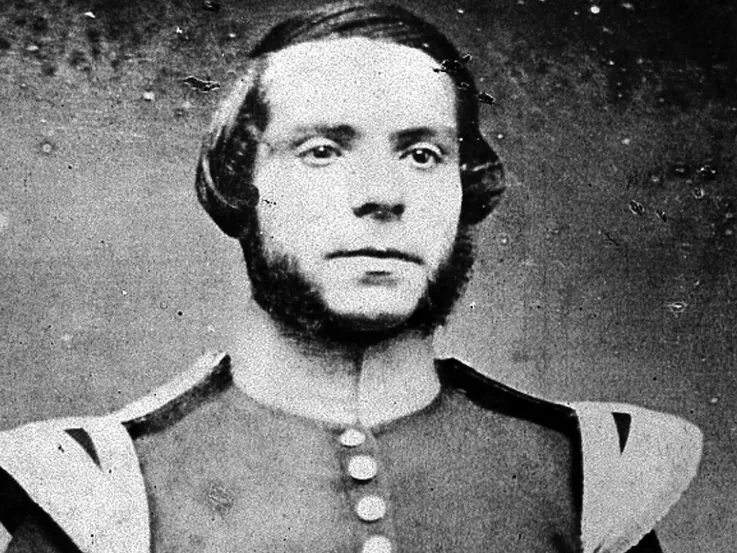

A soldier, man and boy

James Plunkett was born into a military family in Kilkenny, Ireland, in 1878. Aged just 13, he ran away from home and joined 2nd Battalion The Royal Irish Regiment as a band-boy.

Army life clearly agreed with him, and he took advantage of its many sporting opportunities. As well as enjoying cricket and billiards, he became a skilled marksman and an accomplished footballer.

By the outbreak of the First World War (1914-18), Plunkett had already served 23 years and risen to become a regimental sergeant major. He saw action on the Western Front throughout the conflict, taking part in some of its most bitter battles.

He recorded his experiences in a rough diary, from which he later wrote up a fascinating memoir. This not only details his incredible story, but also provides valuable insights into the nature of trench warfare.

Retreat from Mons

Plunkett arrived in France with his battalion on 14 August 1914. As part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), the men immediately advanced into Belgium to meet the German invasion head-on.

As they marched, the British were welcomed everywhere by the local people and Plunkett later described this opening phase as a ‘glorious picnic’.

This mood was soon shattered by their first encounter with the enemy. The battalion played its full part in a famous action at Mons in which the BEF checked the German advance, though at a heavy cost of life.

Following this baptism of fire, the battalion - along with the rest of the BEF - had to endure a demoralising retreat, punctuated by a series of desperate rearguard actions. The defence of the village of Audencourt proved particularly harrowing, with Plunkett astonished that any of his comrades came out alive.

Needless to say, the British suffered many casualties during this period. Among them was Plunkett’s own brother, who was wounded and taken prisoner.

‘However anybody in Audencourt that day escaped being killed or wounded remains a miracle to me. I have never witnessed to date anything like the shell, machine gun and rifle fire we were under there… It was a pitiful sight along the road from the village to about ½ mile to the rear, to see the wounded lying by the roadside, many torn by shell, with nothing but death or capture by the enemy awaiting them.’James Plunkett on the fighting at Audencourt — 1914

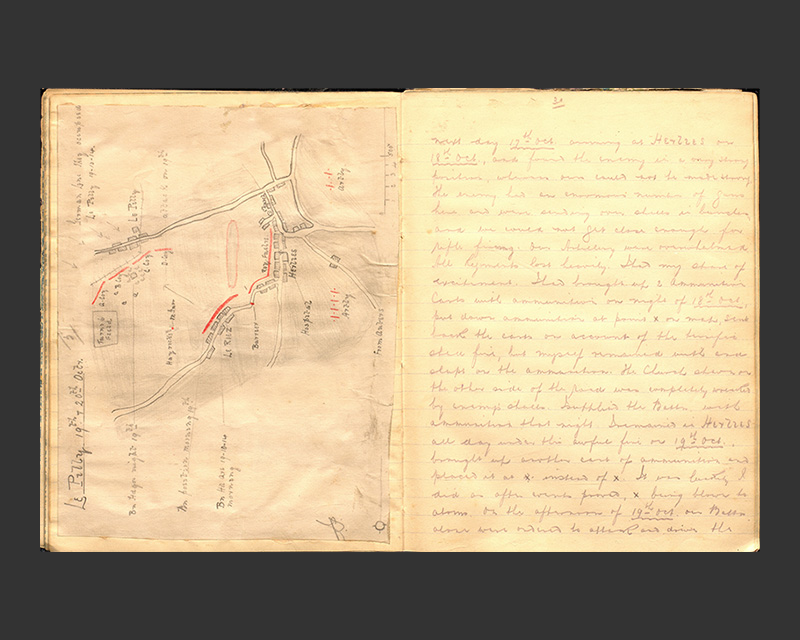

Tragedy at Le Pilly

The gruelling retreat came to an end on 6 September 1914 and Plunkett recorded the enthusiasm with which the men received their orders to advance.

The Royal Irish Regiment now took part in the grand counterattack that unfolded, known as the Battle of the Marne. This culminated in a bloody check on the River Aisne and was, in turn, followed by a series of flanking battles and manoeuvres known to posterity as the ‘Race to the Sea’.

At the Battle of La Bassee (19-20 October), Plunkett's battalion undertook a desperate attack on the village of Le Pilly. The men captured their objective at heavy cost, only to find themselves in an isolated and impossible position, facing a powerful German counterattack. Enfiladed and overrun, the unit was almost entirely wiped out.

Map of Le Pilly showing where Plunkett's battalion was destroyed, 1914 (© The Family of James Plunkett)

At this time, Plunkett oversaw the battalion’s horse-drawn ammunition carts and so was fortunate not to be in the front line. Unable to get through to his comrades, he later recalled how the ‘the groans and moaning in the trenches of our wounded was terrible, it being impossible to get near them to render even first aid as the surrounding ground was swept by fire’.

Plunkett found himself to be one of the most senior of the handful of survivors. Soon afterwards, the remnants of the battalion were pulled out of the line so that it could be reconstituted.

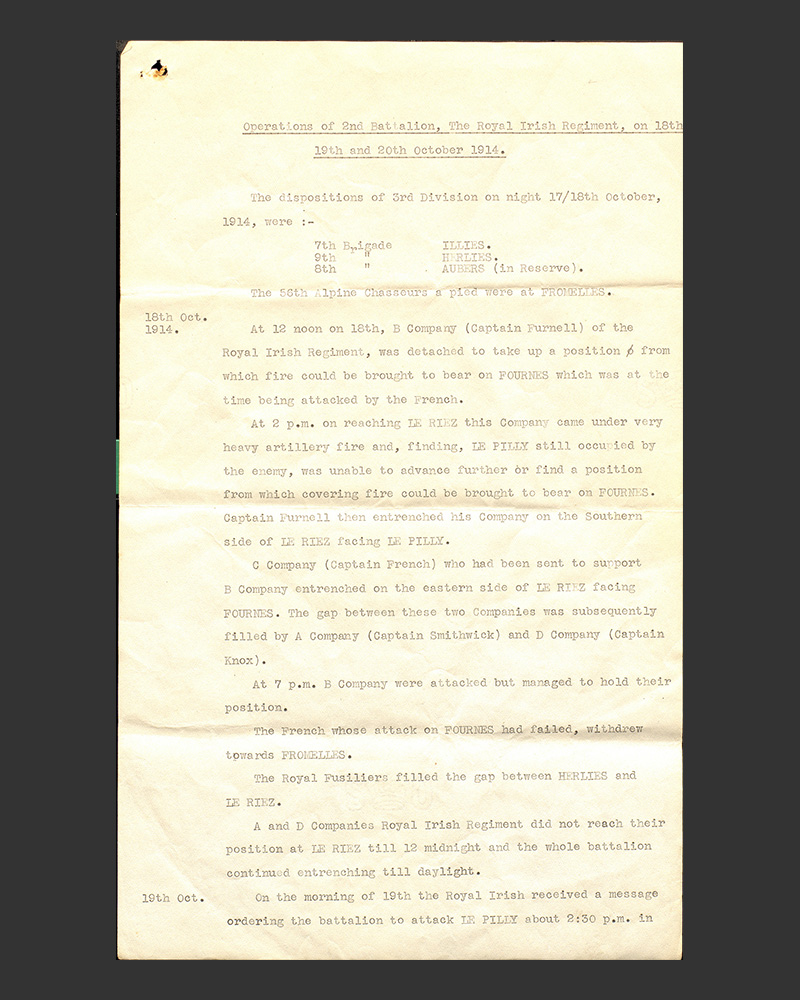

Report by Captain Michael Harrison on the 2nd Royal Irish Regiment's operations at Le Pilly, 1914

‘I cannot give an estimate of the casualties, amongst the rank and file, but should image that all, with the exception of the transport, were either killed or captured.’Captain Michael Harrison, 2nd Battalion, the Royal Irish Regiment, recounting the action at Le Pilly — 1917

A double award for gallantry

Plunkett undertook many heroic actions during this opening phase of the war. These included helping to rescue his wounded commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel St John Augustus Cox, during the retreat from Audencourt and clearing a dead horse from a pontoon bridge at Vailly, on the Aisne, while under heavy fire.

He was honoured with the Distinguished Conduct Medal and became one the first recipients of the newly established Military Cross.

Distinguished Conduct Medal awarded to Regimental Sergeant Major James Plunkett, 17 December 1914

Military Cross awarded to Regimental Sergeant Major James Plunkett, 1 January 1915

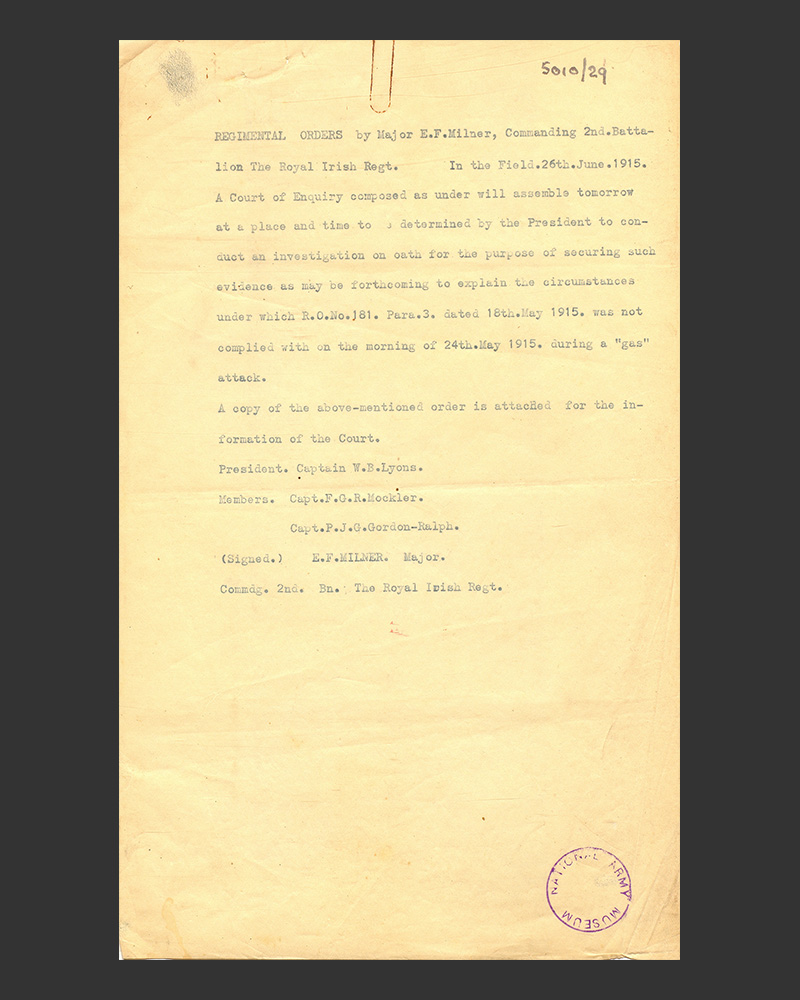

Poison gas

Plunkett returned to the Western Front with his battalion in March 1915, serving in the Ypres sector until June. Here, the Germans pioneered a terrible new weapon - poison gas.

Gas could inflict terrible injuries and sow terror in the ranks. A particularly nasty experience came in the early hours of 24 May at Bellewaarde Ridge, when the Germans unleashed a deluge lasting over five hours as the prelude to a major attack.

The gas engulfed the British line. Many men, including those of 2nd Royal Irish, were driven into headlong retreat. Plunkett himself was rendered unconscious, but was luckily found and revived by two officers.

Realising that the retreat countermanded a recent order prohibiting withdrawals in the face of gas attacks, Plunkett and a few others immediately attempted to rally the men, though with little success. While the attack was eventually halted, the Germans had inflicted severe losses upon the regiment. Casualties included its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Redmond Moriarty.

The withdrawal was the subject of a regimental enquiry in which Plunkett was obliged to give evidence. Although he remained convinced that soldiers could withstand gas attacks, he was later to write of the persistent difficulties involved in maintaining discipline in the face of this cruel and insidious weapon.

‘My own experience through many gas attacks has proved to me, even when not wearing a mask, that the individual can, in most cases, overcome the effect without going back.’Plunkett on poison gas

Life in the trenches

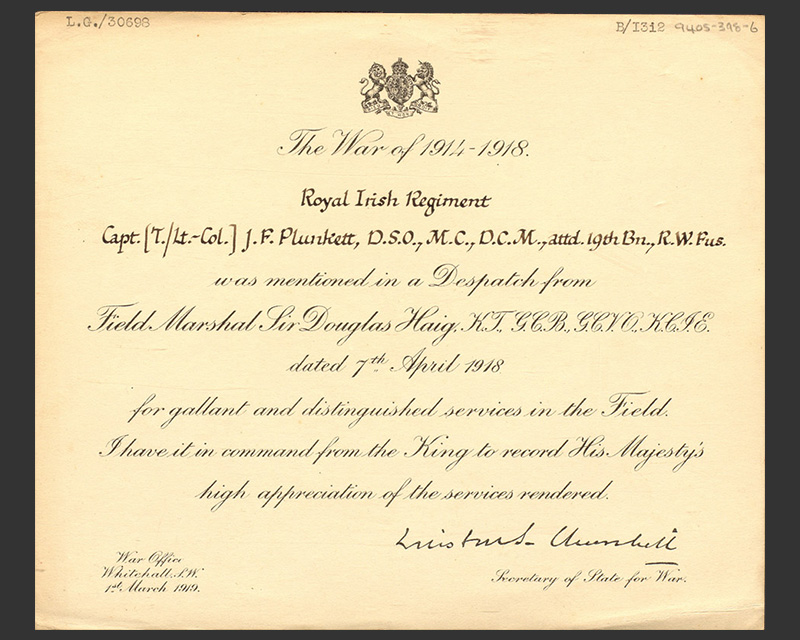

Plunkett’s indefatigable efforts throughout this grim period earned him the further reward of an officer’s commission.

Thereafter, he served with a variety of units - notably including 12th Battalion The Suffolk Regiment, 19th Battalion The Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and 13th Battalion The Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers - in various sectors - including Loos, Gouzeaucourt, Cambrai, and Bullecourt.

During this time, Plunkett experienced all the dangers and discomforts of life in the trenches. He stoically endured the misery of the cold, wet, mud and lice, and the ever-present threats of gas, sniping, shelling and mines.

His penchant for taking potshots at the rats which plagued the trenches almost resulted in a ghastly accident, when a stray bullet narrowly missed his commanding officer.

Trench warfare

A dedicated professional soldier, Plunkett became an expert in trench warfare. He developed a special talent for the difficult and dangerous business of trench raids. These were essential for keeping the enemy under pressure and for gathering intelligence from prisoners, but they often ended in disaster when carried out under careless or inexperienced officers.

Plunkett not only appreciated the finer points of raiding tactics, but also the importance of leading from the front, serving as an example and an inspiration to his men. Emerging as a first-class battalion commander, his service thoroughly merited his award of the Distinguished Service Order, bestowed upon officers in recognition of their courage, leadership and meritorious service.

Bourlon Wood

Plunkett’s finest hour came during the Battle of Cambrai in 1917. This is famous for being the first time that tanks were successfully employed on a large scale.

The attack initially enjoyed great success, breaching the Germans’ formidable ‘Hindenburg Line’ defences and bringing in a large haul of prisoners. However, things soon went awry. The British found themselves unable to exploit their success and vulnerable in the face of a powerful German counterattack.

While the offensive ultimately ended in failure, Plunkett and his men performed their role magnificently. They played a prominent part in the capture of Bourlon Wood on the left flank, a feat made more remarkable by the fact that tanks and smoke shells, which had been promised to support the attack, failed to materialise.

They then held the wood for three days against a ferocious series of counterattacks, engaging in some of the most vicious close-quarter fighting of the war.

‘I have fought with many regiments in this war, but the achievements of the 19th Bn Roy Welch Fusiliers & remainder of 119 Brigade taking Bourlon Wood on 23rd November 1917, with no assistance from tanks, smoke barrages, etc, and only a few minutes preliminary artillery bombardment, capturing at least 500 prisoners with many machine guns, then repelling counter-attacks for 3 days without sleep, subsisting on iron ration food only, handing over the wood intact, marching 15 miles to the rear, after the brigade had suffered 75% casualties both in officers and men, and finishing the last mile of the march in high spirits, I place second to none of any other.’Plunkett on the conduct of his troops at Bourlon Wood — November 1917

Contempt of danger

Plunkett had been recommended for the Victoria Cross for his bravery at Bourlon Wood, but this was later downgraded to a bar to his Distinguished Service Order. Nonetheless, the citation to this award fully recognised the leadership and heroism that he had displayed.

Further heroics were to follow during the final victorious Allied offensive of 1918. On 27 August, Plunkett led his battalion in a daring flank attack against a German position at Rue Pruvost, which enjoyed complete success and saw the capture of seven machine-gun posts.

For this, he was awarded another bar to his DSO, with the citation praising his ‘absolute contempt of danger’ and highlighting ‘his determination and fine personal example’ as the chief cause of their success.

Distinguished Service Order with two bars, awarded to Lieutenant Colonel James Plunkett

‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during sixty hours’ hand-to-hand fighting. When our line was pressed back by a counter-attack and the men began to waver on the right, he reorganised them and succeeded in re-establishing our old line. When reinforcements arrived, he organised and led a successful counter-attack. He carried out in person many daring reconnaissances, and undoubtedly saved the situation at many critical moments by his prompt action.’Citation for Plunkett’s first bar to his Distinguished Service Order — 1917

Close shaves

In the course of his service, Plunkett had innumerable close shaves. During some periods, these were almost a daily experience. On many occasions, shells landed nearby, but either failed to go off, narrowly missed him, or left him only lightly wounded. Several times, he described leaving a place only for it to be immediately obliterated by shell fire.

Perhaps most remarkable was an incident at Bourlon Wood. Plunkett spotted an enemy who was about to take aim at him, but by quick thinking, lightening reactions, and sheer good fortune, he was able to take aim and get his shot off first.

A heavy toll

Despite escaping serious injury, the war still took a heavy toll on Plunkett's health. His many ailments included deafness and respiratory problems, as well as a heart attack.

His service at the front was interrupted by several long bouts of convalescence. At one stage, he had trouble persuading an Army medical board that he was fit to return to action. And, ultimately, it was owing to poor health that he retired from the Army in 1922.

Full honours

Plunkett was clearly in his element as a front-line commander. Indeed, the end of the fighting in 1918 came as something of a disappointment to him as it prevented his promotion to brigadier-general, a rank he felt was in his grasp had the conflict continued a little longer.

He was, however, able to console himself with the cheering thought of returning to his wife and family, and the satisfaction of a job well done.

His full wartime honours were: Distinguished Service Order with Two Bars; Military Cross; Distinguished Conduct Medal; French Croix de Guerre; and five mentions in despatches.

In May 1930, he was given the further honour of joining the Military Knights of Windsor, one of Britain’s most ancient military establishments. He resided at Windsor Castle for the next 17 years. However, as he continued to be dogged by ill-health, he was then permitted to move to Sussex, where he died in 1953 aged 75.