Explore more from First World War

Paul Sarrut: Interpreting the Army on the Western Front

7 minute read

Early career

After completing his French national service in the 40th Regiment of Infantry in 1906, Camille Georges Paul Sarrut (1882-1969) went on to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

By 1909, he was an accomplished professional artist and engraver who exhibited at the Salon des Artistes Français under the name of Paul Sarrut.

Paul Sarrut, c1915 (Image courtesy of Richard van Emden)

Interpreter

Two days after the general mobilisation of the French Army in August 1914, Sarrut re-joined from the reserves. Now 32 years old, Corporal Sarrut was immediately seconded to the British Army as a translator for the Indian and British troops in France.

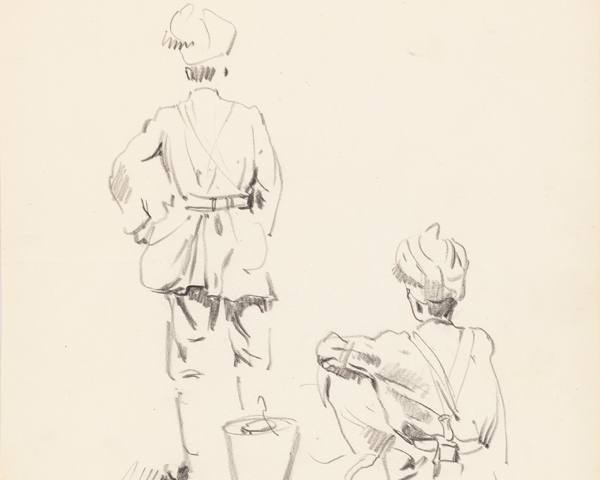

This role gave him the opportunity and the time to make a series of detailed sketches and portraits of British, Indian and French soldiers. Most of the sketches are signed and dated. Helpfully, he often recorded the regiment and location on them too.

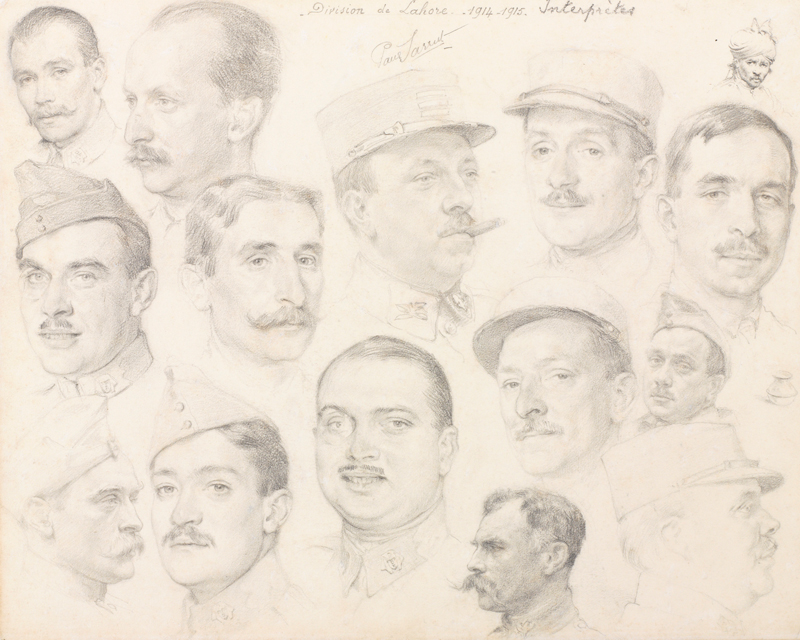

Over the next two years, Sarrut sketched portraits of all his fellow British and French interpreters attached to the 3rd (Lahore) Division. The figure top-left in the image below is believed to be a self-portrait.

Indian Corps

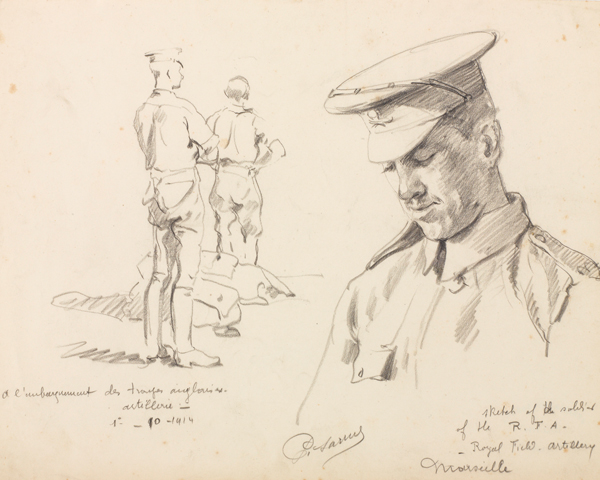

In 1914, Sarrut was posted to Marseille on the south coast of France. The port was already bustling with soldiers arriving from across the globe and awaiting embarkation to other theatres of the war.

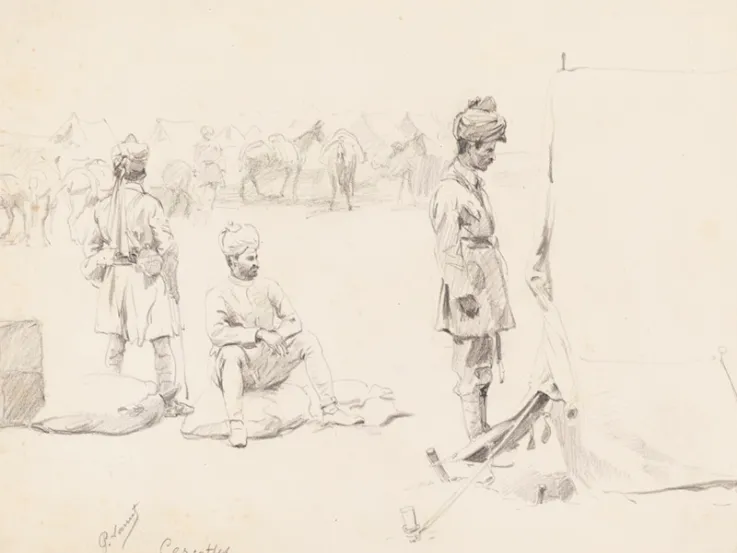

The Indian Corps had started to arrive at Marseille from 30 September 1914. Sarrut drew simple line sketches depicting their arrival, life in camp and their progress north across France to the Western Front.

‘Groupe de hindous. Marseille au départ’, 1 October 1914 (Purchased with the assistance of the Art Fund © The Estate of Paul Sarrut)

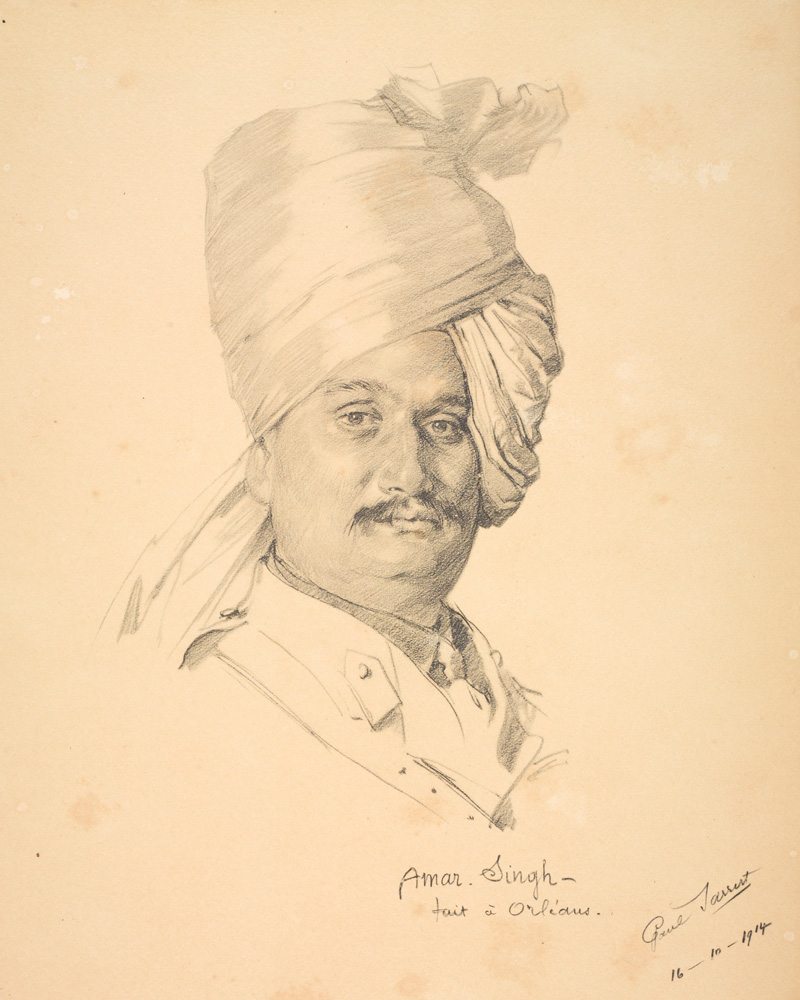

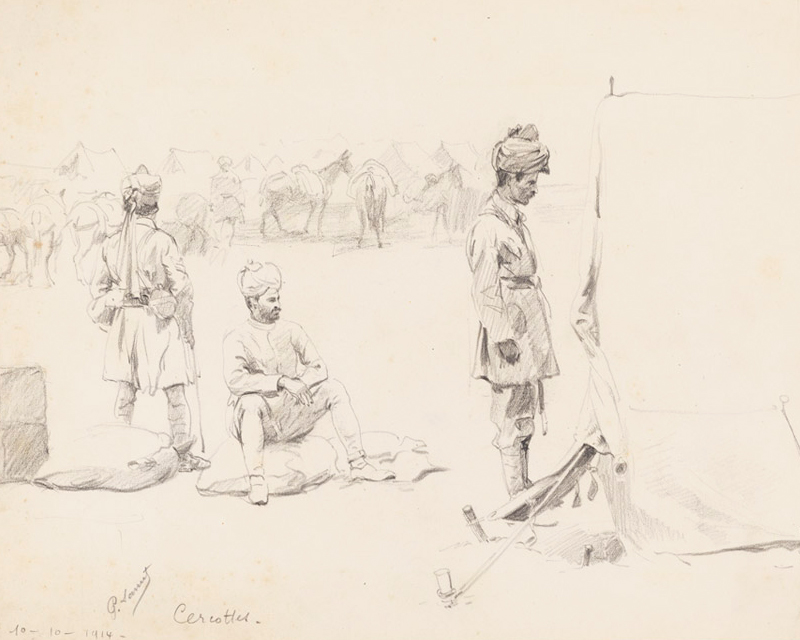

By 10 October, Sarrut and the 3rd (Lahore) Division were in Cercottes, just north of Orléans. The sensitive sketches that he made there of the soldiers and officers of the Indian Army are far more detailed than his quick studies in Marseilles.

‘Cercottes’, 10 October 1914 (Purchased with the assistance of the Art Fund © The Estate of Paul Sarrut)

Captain Amar Singh

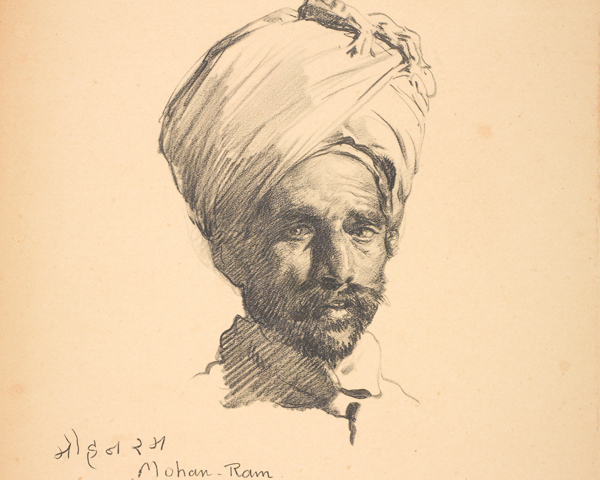

He began to draw very detailed studies of officers and other ranks of the Indian Army, often annotated with the names of the sitters.

Captain Amar Singh served as an aide-de-camp with the 9th (Sirhind) Brigade, part of the 3rd (Lahore) Division. He kept a diary which gives us a valuable insight into his unit's part in the fighting on the Western Front.

'There is no doubt that the Indian troops have done very well indeed in this war so far... The conduct of the troops has been wonderfully good both in the firing line and in the billets... A great trouble under which we have laboured is that whenever we fail in the slightest degree anywhere people raise a hue and cry whereas if a British troop fails under the same circumstances no one mentions it. The Indian troops had done very well all along but when we had the reverse at Givenchy and Festubert there was a hue and cry. However no one at that time said that there were British troops in it as well... I do not know what is expected of the Indians. After all a man can give his life up and no one can say that the Indians have been sparing themselves in any way. What more proof can be required than one of the Gharwal Regiments who were six hundred strong at Neuve Chapelle in March last and of them only fifty-five came back.’Diary of Captain Amar Singh — c1916

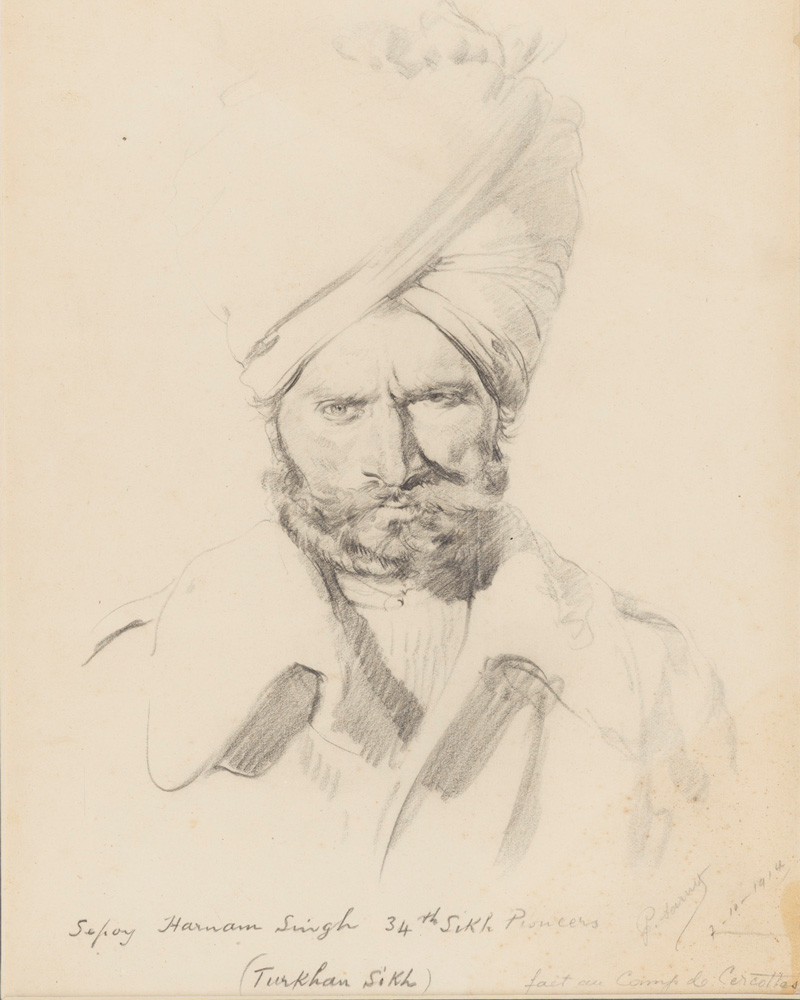

Sepoy Harnam Singh

On 7 November 1914, Sarrut sketched a portrait of Sepoy Harnam Singh of the 34th Sikh Pioneers. Tragically, Singh was killed in action just 16 days later.

His face became one of the most famous images of an individual Indian soldier in the First World War. It was published in 'The Illustrated War News' on 17 February 1915 and as a popular postcard entitled, ‘Types de l’armée de l’Inde’.

For the British public at the time, Harnam Singh came to be seen as a ‘Tommy Atkins’ figure, representative of all Indian soldiers. Harnam Singh is also the most common Sikh name in the database of men killed in action, compiled by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

General Sir James Willcocks, commander of the Indian Corps in France, wrote a poem about an archetypal Indian soldier who survived the war. Entitled ‘A Poem for Harnam Singh’, it was published in 'Blackwood’s Magazine' in 1917.

'Beneath an ancient pipal-tree, fast by the Jhelum’s tide, In silent thought sat Hurnam-Singh, A Khalsa soldier of the King: He mused on things now done and past, For he had reached his home at last, His empty sleeve his pride'.Opening stanza of ‘A Poem for Harnam Singh’ by General Sir James Willcocks — 1917

Keeping warm

A number of Sarrut’s sketches depict the soldiers trying to keep warm. The cold weather in October and November 1914 had a serious impact on the health of Indian dholi-bearers (or stretcher-bearers), carrying out their duties in difficult conditions. This was particularly true for those who were still wearing the sandals in which they had arrived in France.

‘Locon’, 26 November 1914 (Purchased with the assistance of the Art Fund © The Estate of Paul Sarrut)

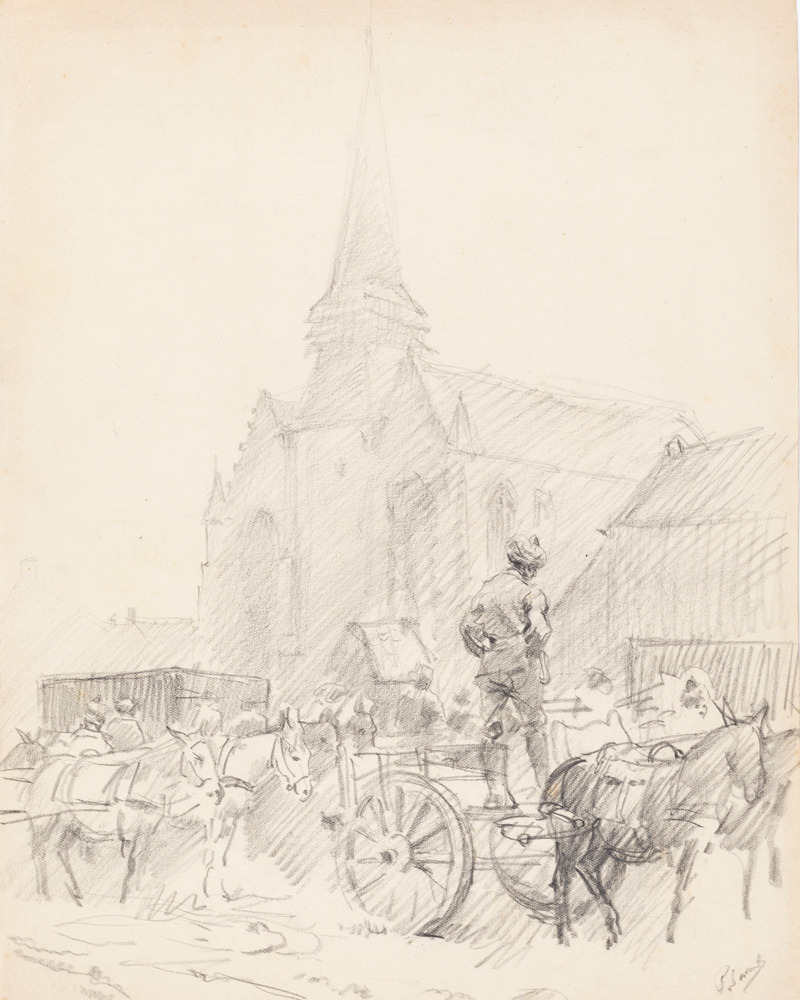

Sarrut spent much of the winter of 1914-15 in the town of Locon, 8km (5 miles) north of Béthune, in the Pas-de-Calais area. The church of Saint-Maur in the background of the drawing below was almost completely destroyed during the war, but was later rebuilt.

'Locon', 21 February 1915 (Purchased with the assistance of the Art Fund © The Estate of Paul Sarrut)

British soldiers

Promoted to sergeant on 1 July 1915, Sarrut carried on sketching the men of the Indian Corps until they were sent to Mesopotamia in December of that year.

After their departure, he continued in the role of interpreter for the British Army in France. In July 1916, he was in the trenches of the Western Front drawing British ‘Tommies’ near Vermelles.

He was appointed adjutant in 1917. The following year, he was still sketching British officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs) at Amiens before he was demobbed on 6 March 1919.

Portfolio of prints

After the war, Sarrut engraved a selection of his wartime drawings. These were sold as a portfolio under the title, 'British and Indian Troops in Northern France, 70 War Sketches, 1914-1915'. The limited edition of 250 copies was published by H Delépine of Arras, France, in about 1920.

The original sketches of Sarrut’s wartime subjects were exhibited at the Grafton Galleries in London in the winter of 1920 and were praised in the British press. 'The Connoisseur' called them a ‘valuable record’ of the British and Indian troops in northern France.

In addition to a full set of these prints, the National Army Museum holds 49 of Sarrut’s original sketches, some of which have never been published. Thirteen of these were purchased in 2021 with the generous support of the Art Fund. You can now see them on the Museum's website.