Explore more from In Their Own Words

In Their Own Words: Lieutenant Colonel Michael Harrison

8 minute read

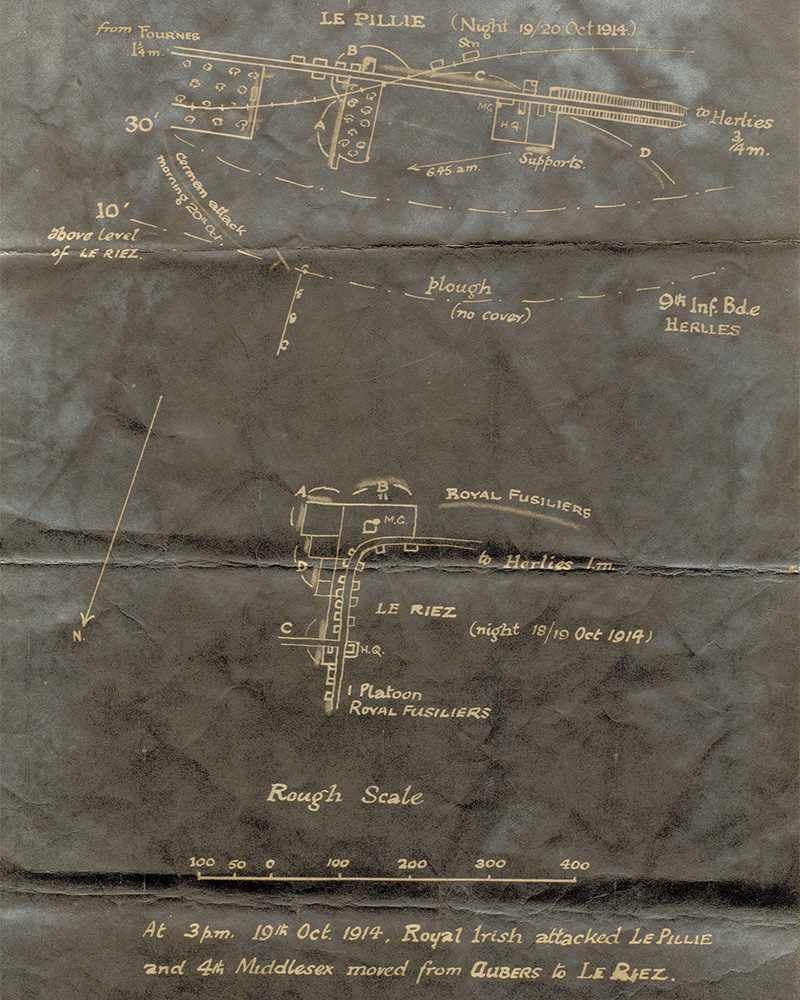

Disaster at Le Pilly

On the outbreak of the First World War (1914-18), Michael Charles Cooper Harrison was a 26-year-old subaltern serving in 2nd Battalion, The Royal Irish Regiment. Deployed to the Western Front, his unit took part in the conflict’s harrowing early encounters, which saw the British Expeditionary Force play a vital role in resisting the German advance into France and Belgium.

This epic contest began with the famous clash at Mons in August 1914 and culminated with the disaster of the Battle of Le Pilly in October. Here, Harrison's battalion was encircled and almost wiped out. Hundreds were killed; hundreds more were taken prisoner, almost all of whom - including Harrison - were wounded.

‘Our losses and the strenuous nature of the fighting in those early days absolutely astounded me.’Michael Harrison reflecting on the opening engagements of the war

Escape artist

Harrison now faced years of internment as a prisoner of war. The first weeks were the hardest. Treated contemptuously by many of his German captors, he was lucky to survive. However, he went on to make a full recovery from his injuries and soon began working on a plan to regain his freedom.

Escape posed three major challenges: how to get out of the camp; how to make it across enemy country; and, finally, how to get over the frontier.

To overcome these problems, Harrison and his comrades utilised a range of tactics, including disguises, coded messaging, secret equipment stashes, tunnelling, forged documents and lock-picking. These he combined with bluff, guile and gritty endurance to mount a series of determined escape attempts.

‘Occasionally one would greet us with, “Englishmen are you thirsty?” And pouring out some liquid would throw it in our faces. I have never known a train have so many long halts. I felt as if I would die of thirst.’Michael Harrison recounting his treatment as a prisoner of war during a train journey into Germany in 1914

Breakout from Magdeburg

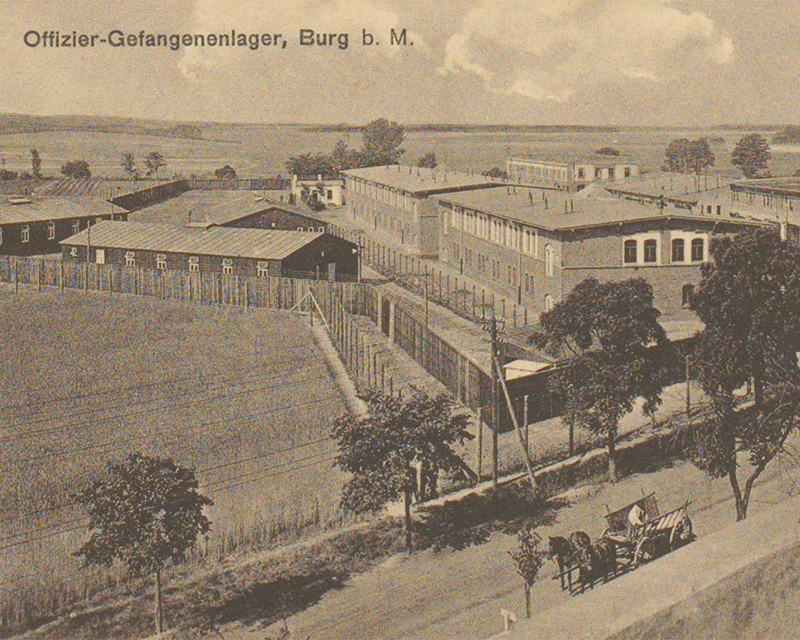

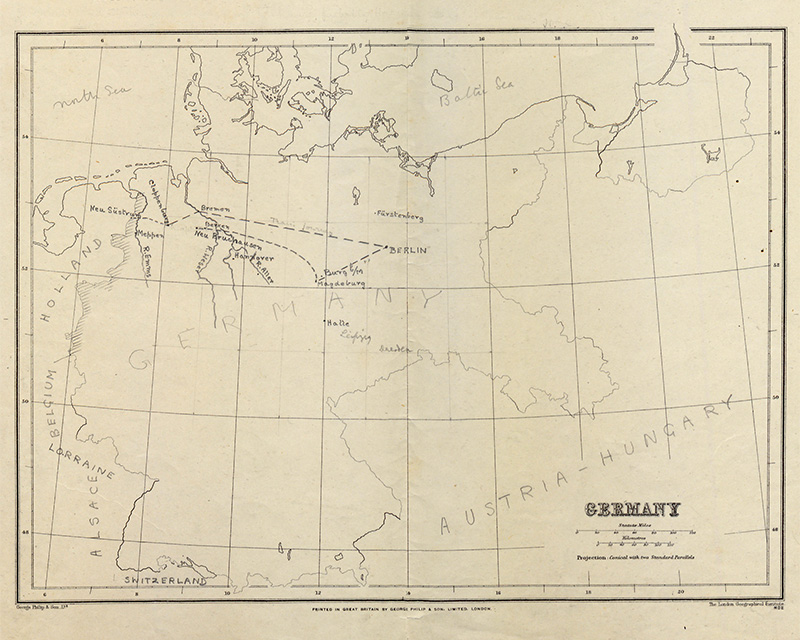

Harrison made his first escape attempt on 18 November 1915 from a camp at Burg bei Magdeburg, about 75 miles (120km) west of Berlin.

Planning to bluff his way out in disguise, he got in touch with his tailor back in England and was able to obtain a Grenadier Guards greatcoat, which he mistakenly believed would be similar in colour and style to that of a German officer.

He was accompanied on this mission by fellow internee Henry Cartwright, who managed to acquire a cape from a Russian prisoner for the same purpose. Both garments were skilfully altered and combined with other props, such as wooden swords and cigars, to transform the two men into a passable pair of German officers.

Choosing their moment carefully, the duo swaggered brazenly out past the camp guards, then made their way north towards the Baltic coast, where they hoped to find passage across the sea to Denmark.

Playing drunk

Sleeping in barns by day and walking at night through the bitter German winter, the pair endured much hardship and a series of close shaves during their nine-day cross-country trek.

Their most remarkable encounter took place in the early hours of 27 November, when a German soldier accosted them on the outskirts of the port city of Rostock. Speaking no German, the men had prepared a plan for a situation such as this, in which they would both pretend to be drunken Danish sailors.

Their performance was capped by Harrison, who simulated being sick in the gutter and then staggered towards their interrogator and vomited a mouthful of snow and chocolate over the man’s expensive-looking coat. This greatly enraged the soldier, but also convinced him of their credibility.

Just as the men were sizing up a Danish ship on Rostock docks, they were discovered by a German police dog and duly arrested.

‘He screamed with rage, and, hurling Harrison violently away from him, treated us for three minutes to the choicest flow of obscenities to which he could lay his tongue.’Henry Cartwright recounting the reaction of the German soldier who accosted them outside Rostock

The Torgau tunnel

Harrison’s next two serious attempts were also valiant failures. On 18 August 1916, he escaped from Torgau, a camp situated in the heart of Germany, about 75 miles (120km) to the south of Berlin. The escape was part of a mass breakout via a tunnel excavated with painstaking care over several months.

As well as helping with the digging, Harrison meticulously prepared a stash of supplies and equipment for the breakout by sending secret messages home to Britain. The equipment he received included maps, torches and compasses sent in carefully packed parcels containing false-bottomed tins.

After breaking out, Harrison and a French companion undertook another arduous journey to the Baltic coast before, again, suffering the bitter frustration of being recaptured on the brink of success.

‘I suppose that I must now have been in possession of about the finest mobilisation kit that any prisoner ever possessed.’Harrison recounting his preparations for the breakout from Torgau

An unexpected reunion

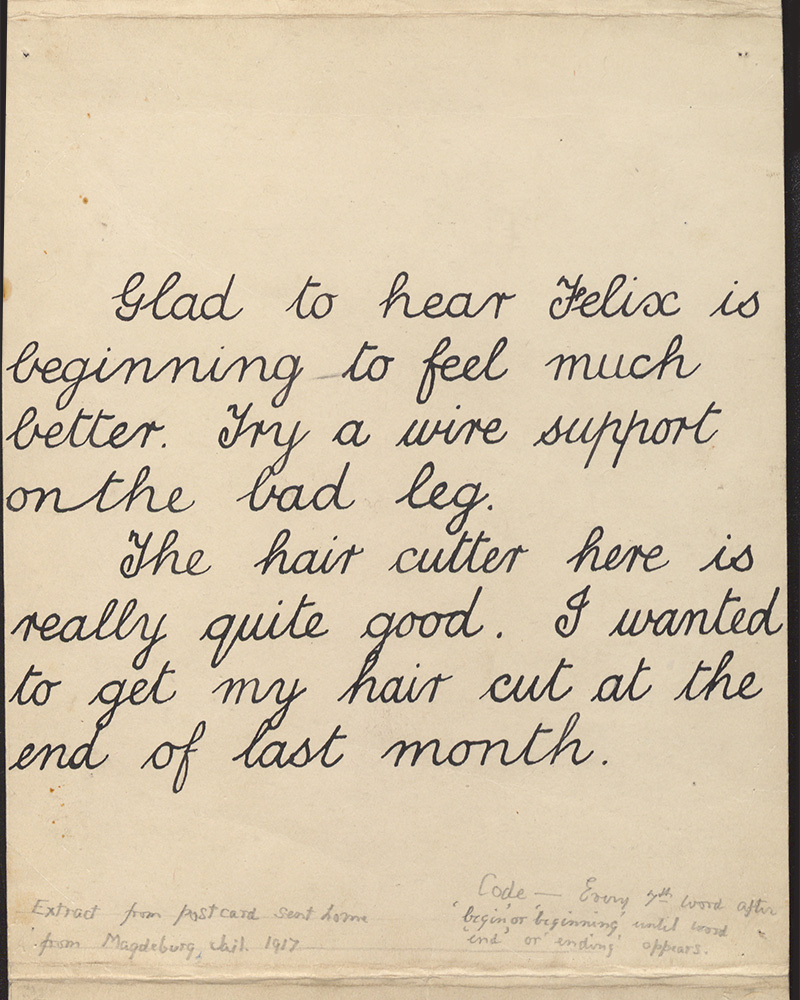

Another major escape was mounted in May 1917, this time from Magdeburg prison - not far from Harrison's previous place of confinement at Burg bei Magdeburg. Here, he had been unexpectedly reunited with his old friend Cartwright.

By now a skilled lock pick, Harrison succeeded in copying the prison’s master key and getting a skeleton version made. Combined with an elaborate distraction mounted by their prison comrades, this enabled the pair to break out once more.

In preparation, Harrison had again re-worked his greatcoat. Hoping to make it pass for a civilian garment, he shortened it, added a new collar and used a chemical disinfectant to dye it chocolate-brown.

An artful escape

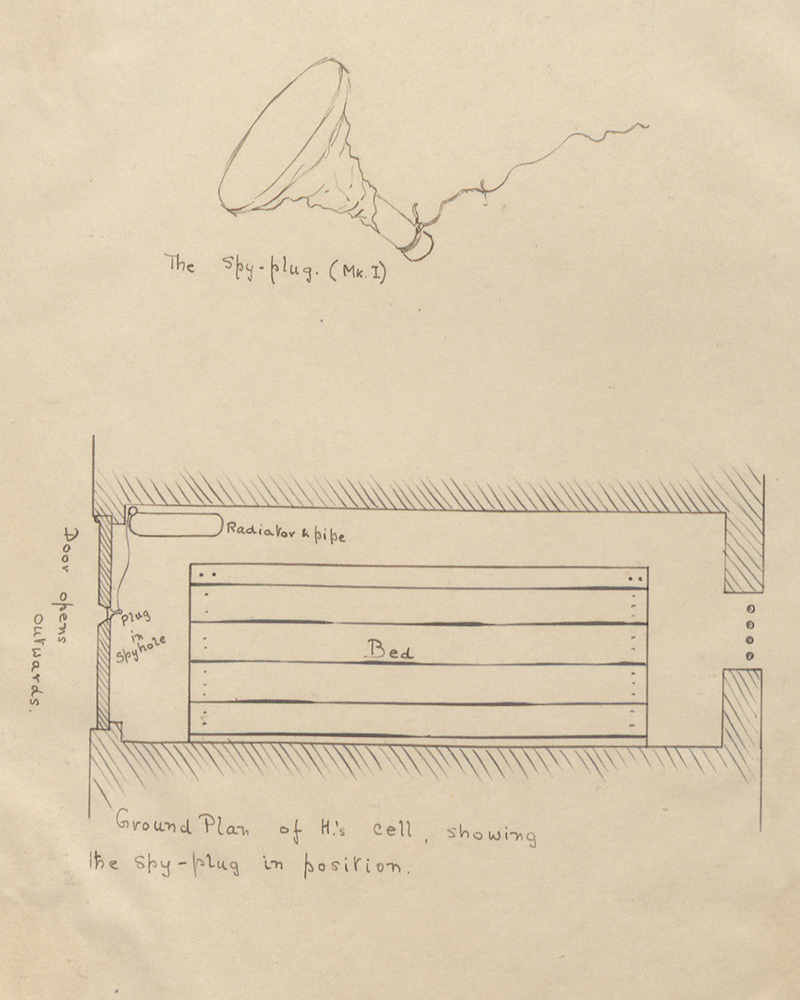

To enable Harrison to undertake this work in secrecy, Cartwright painted a picture of a scantily clad woman, which he used to plug the cell door's spyhole. By an ingenious mechanism, this 'spy-plug' would disappear behind a radiator as soon as the door was opened, confounding any attempts to have it confiscated.

The guards found all of this rather amusing. But Harrison fell foul of a visiting German general who put him up on a charge of ‘insulting superior officers' by placing 'an immoral picture' in his cell door.

Having made their escape, the two men headed west this time, hoping to get across the border to the Netherlands. Once again, after many days on the run, they were caught.

‘The “hanging” of the picture aroused great excitement amongst the prison officials and camp commandant’s staff. Their early efforts to loot it were too ridiculous to narrate, but as no one suspected its real object I was able to get on with my work in comparative peace. The sentries soon contented themselves by nudging each other on the passage and treating it as a huge joke, possibly because they could see how infuriated were their own officers.’Harrison recounting the reaction of the prison guards to the picture he used to disguise his elicit tailoring

Success at Ströhen

Harrison eventually ended up at a camp at Ströhen in the north-west of Germany. From here, he succeeded in breaking out in August 1917 and finally made his way over the Dutch border to freedom.

Repatriated in September, his triumph was made all the sweeter by a reception at Buckingham Palace, where he enjoyed the privilege of recounting his adventures in a private audience with King George V.

‘I leave it to my readers to imagine the welcome that awaited us from our friends at home.’Michael Harrison

Back to the front

But Harrison’s story did not end there. Early the next year, he re-joined his battalion and returned to the front, just as the war was reaching its bloody climax.

In the spring of 1918, the Germans unleashed a massive offensive in a last-ditch attempt to win the war. Harrison was awarded the Military Cross for his courage in the desperate and chaotic fighting that ensued.

Later that year, the Allies mounted their final, victorious advance. During this offensive, Harrison - now a temporary lieutenant colonel - enjoyed the distinction of being the last officer to command the 2nd Royal Irish in action. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his leadership and gallantry.

He was wounded yet again, but not seriously, and returned home in time to serve as best man at Cartwright’s wedding.

Recognition

After the war, a bar was added to Harrison’s Military Cross, awarded ‘in recognition of gallant conduct and determination displayed in escaping or attempting to escape from captivity’.

Harrison and Cartwright’s joint memoir, 'Within Four Walls', was published in 1930. A digitised version is freely available to access online via the Internet Archive. It went on to become a classic of the prisoner-of-war escape genre and may well have inspired many of the great escapes of the Second World War (1939-45).

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.