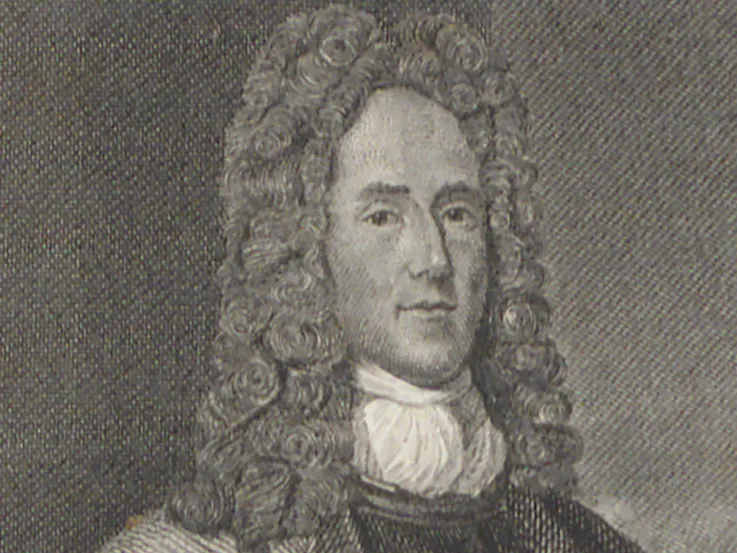

Portrait of Richard Symonds, c1638-80 (Trustees of the Weston Park Foundation / Bridgeman Images)

A scholar and a squire

Richard Symonds was born in 1617 in the village of Black Notley near Braintree in Essex. His family were members of the landholding gentry there. Introverted and studious, Symonds developed an interest in a wide range of subjects, including art and antiquities.

After attending Emmanuel College, Cambridge, Symonds took advantage of his family connections to secure a position in the legal profession as a cursitor (a clerk in the Court of Chancery). In 1636, his father died, his mother following in 1641. As the eldest son, Symonds inherited the family estate and so took his place as Black Notley’s local squire.

He was soon drawn into the religious and political disputes, between those loyal to King Charles I and those loyal to Parliament, that were fast dividing the nation, its communities, and even its families.

Civil War

Perhaps owing to his academic background, Symonds developed a deeply conservative outlook and emerged as a staunch Royalist. This placed him at odds with members of his own family, and many of his neighbours in the county of Essex, who were sympathetic to the Parliamentarian cause.

Attitudes hardened following the outbreak of civil war in the summer of 1642, and Symonds's situation became increasingly uncomfortable. By March 1643, he had lost his position at the Chancery, his estate had been confiscated, and he had been imprisoned at the hands of the Essex Parliamentarian - and future 'regicide' - Miles Corbett.

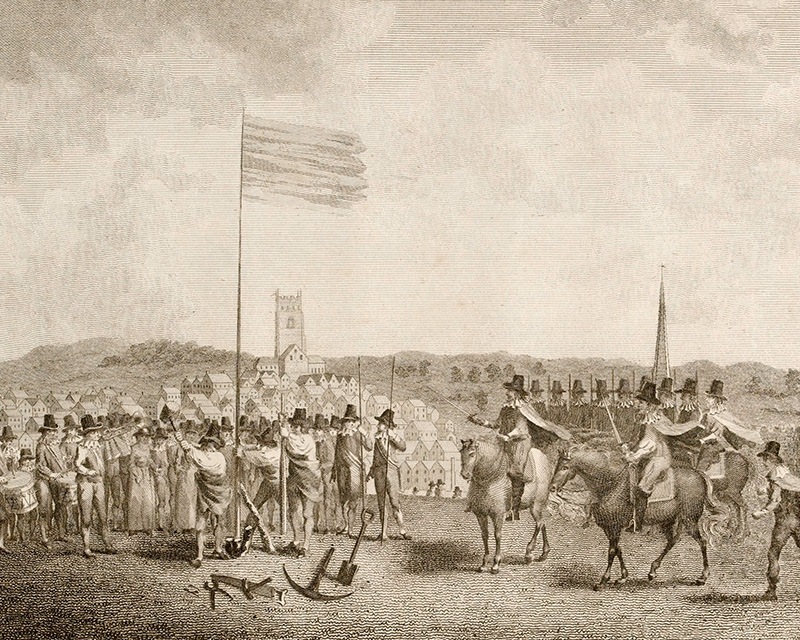

The King’s Lifeguard

After making his escape in October 1643, Symonds travelled to Oxford, where the King had established his headquarters. Here, he joined the senior troop of the King’s Lifeguard of Horse, which was commanded by Lord Barnard Stuart.

Comprising both cavalry (horse) and infantry (foot) units, the King’s Lifeguard represented the military elite. The cavalry was especially prestigious. Barnard’s Troop was composed entirely of wealthy gentlemen. As a member of this unit, Symonds enjoyed a status that more than compensated for his somewhat lowly rank of trooper.

The Royalist Army

In April 1644, Symonds marched out from Oxford with the King’s army, as it embarked on one of its most important campaigns. It was now that he began to keep a diary, a practice that he would continue until the first phase of the Civil War came to an end two years later.

By this time, the situation for the Royalists was already bleak. A string of victories in 1643 had enabled them to secure much of the North and West of England. However, their hopes of invading London and the South East had been dashed with their defeat at the Battle of Cheriton in March 1644.

Furthermore, an alliance between Parliament and the Scots threatened to destabilise the Royalist position in the North. This would result in a disastrous defeat for Royalist forces at Marston Moor, near York, in July of that year.

Victory at Lostwithiel

Firmly on the defensive, the King’s most urgent task was to evade a deadly pincer movement by two Parliamentarian armies, commanded respectively by Sir William Waller and Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex. Deft manoeuvring, combined with the mistakes of his enemies, helped the King to succeed brilliantly in this endeavour.

When Essex broke off his pursuit to undertake an invasion of the West Country, the King was able to inflict a significant defeat upon Waller at Cropredy Bridge, north of Oxford. He then pursued the Earl of Essex, eventually trapping him and compelling the surrender of his army at Lostwithiel in Cornwall in early September.

‘This was a happy day for his Majesty and his whole army, that without loss of much bloud this great army of rascals that soe triumphed and vaunted over the poore inhabitants of Cornwall, as is they had been invincible, and as if the King had not been able to follow them, that ‘tis conceived very few will get safe to London, for the country people whome they have in all the march so much plundered and robd that they will have their pennyworths out of them.’Symonds on the Royalist victory at Lostwithiel — 2 September 1644

Defeat at Naseby

The victory at Lostwithiel helped to revive the King’s fortunes, but it was insufficient to turn the tide of war in his favour. The campaigning season ended with the Second Battle of Newbury in October. This inconclusive encounter left the Parliamentarians frustrated, but still very much in the ascendency and determined to reconstitute their army on a more professional basis.

The scene was now set for the decisive campaign of 1645, which culminated in a devastating defeat for the King at the Battle of Naseby in June. The Royalists managed to drag out the war for another year, fighting an increasingly bitter and desperate rearguard struggle.

During this time, Symonds left the King's Lifeguard and joined mobile Royalist forces operating in Wales and the East Midlands, waging what today might be called a guerrilla war. In March 1646, he finally accepted the hopelessness of his position, made his peace with the Parliamentarians, and returned home.

A diligent diarist

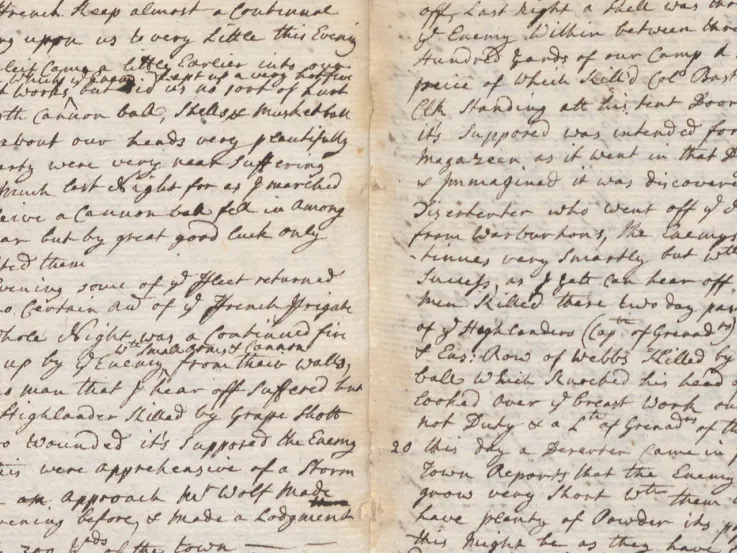

Entitled ‘A Diary of the Marches and Moovings of His Maties [i.e. Majesty's] Royall Army’, Symonds's four-volume account was written in snatched moments while on campaign. A digitised version is freely available to access online via the Internet Archive. The difficulties of maintaining a diary in these circumstances is reflected by the unbalanced and fragmentary nature of the information it contains.

The early phase of the campaign is more detailed, and his account of the Battle of Lostwithiel is of particular importance. However, the diary becomes increasingly sparse as the Royalists’ fortunes turned sour.

It's clear that Symonds was also keen to cultivate his academic interests throughout his time in service. His military jottings are interspersed within long passages on subjects such as art, topography, heraldry and architecture, inspired by excursions to historic sites during periods of leisure.

‘This day a foot soldjer was tyed (with his sholders and breast naked) to a tree, and every carter of the trayne and carriages was to have a lash; for ravishing two women.’Richard Symonds, diary entry — 24 May 1645

An historic document

Although his style is mostly dry and impersonal, Symonds does occasionally add colourful details. He comments on the brutal punishment meted out to ill-disciplined soldiers and offers a dramatic account of his unit in action at Newbury. These serve to enliven his narrative and convey something of the harsh realities of the struggle.

Symonds's diary remains the only known account of the Civil War by a Royalist who was not an officer. However, his status as a gentleman in an elite corps means that it cannot truly be said to give us the perspective of an ordinary soldier.

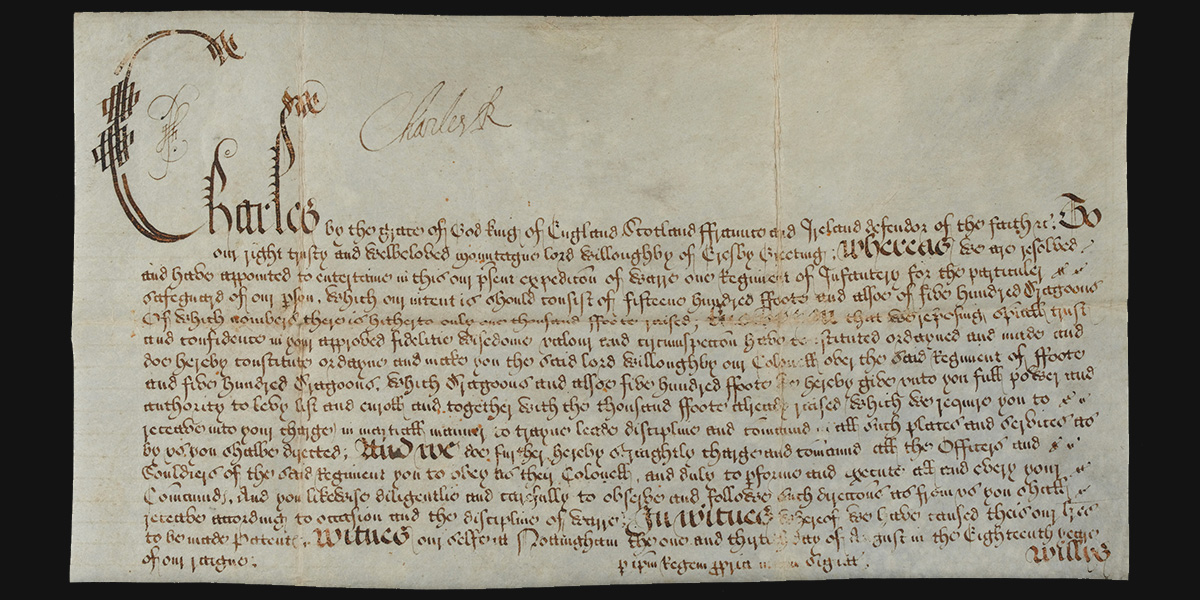

Despite its drawbacks, the diary is of considerable historic value. Symonds succeeded in documenting many of the key events of the war and complemented this with useful additional material, such as the composition of various forces, and copies of intelligence documents, letters and news bulletins.

Moreover, the importance of his work is greatly magnified by the rarity of diary-keeping in this period. As such, his account constitutes a precious legacy for posterity.

‘About the same time, 4 of the clock, their bodyes of horse approached towards our field at the bottome of the hill neare the church… one body came into our field, [and] charged Sir John Campsfeld’s regiment, which stood them most gallantly. The King’s regiment being neare, drove at them, which made them wheel off in confusion, and followed them in the chase, made all their bodies of horse run in confusion, killed many, besides musqueteers that had lined the hedges and playd upon us in the chase till wee cut their throats.’Symonds describing his regiment in action at the Second Battle of Newbury — 27 October 1644

Later life

In early 1649, Symonds took the opportunity to travel in France and Italy. Taking up residence in Paris and Rome, he indulged his love of art and antiquities, writing notes on artists and their works, which are highly valued by art historians to this day.

He returned to England in December 1651 and continued with his academic pursuits. He also maintained an interest in public affairs and kept in touch with his old Royalist comrades. These activities landed him in trouble in 1655, when he was implicated in a failed Royalist plot. He was imprisoned, but escaped serious punishment and was released later that year.

Symonds died in England in June 1660, aged 43. He had lived just long enough to see the restoration of King Charles II, and thereby the ultimate victory of the Royalist cause for which he had fought.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.