The missing

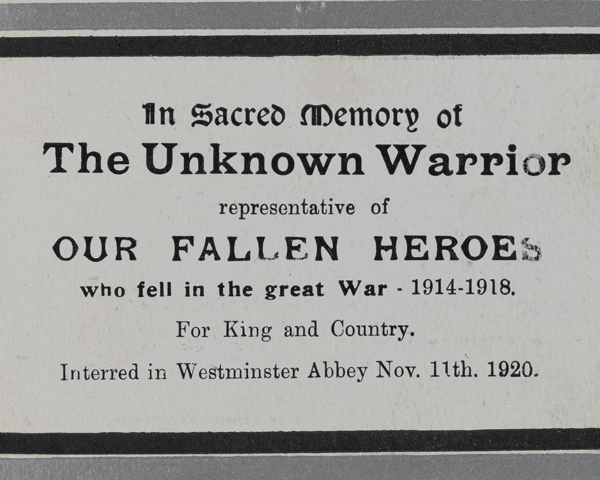

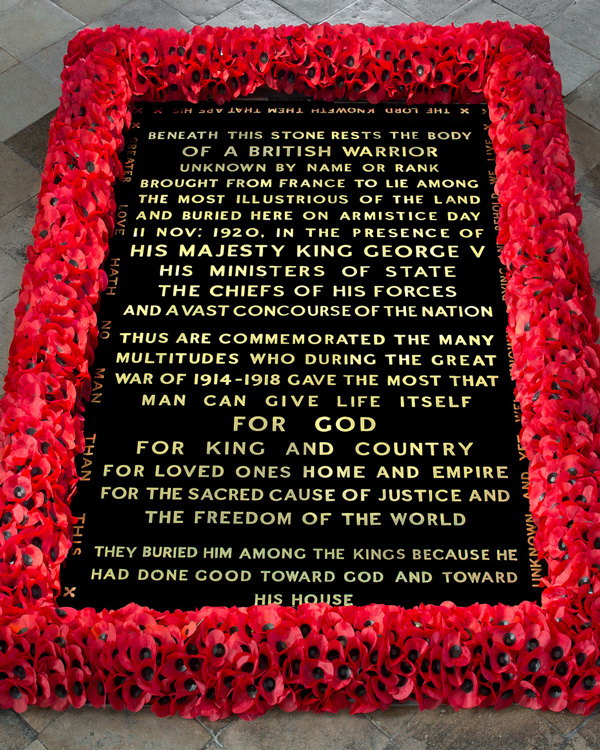

The grave of the Unknown Warrior contains the remains of one of the many thousands of British service personnel killed in the First World War (1914-18), but whose bodies could not be identified. Although created to honour and commemorate all those who died in British service, it also serves as a special symbol of those recorded as missing in action.

The Unknown Warrior was carried back from France and then reverently buried in London's Westminster Abbey on 11 November 1920. His grave is one of Britain’s most important war memorials. Over a million people queued up to visit it in the week following his burial, and it still attracts large numbers of visitors.

Origins

One of the longest-standing mysteries surrounding the Unknown Warrior is who came up with the idea. This confusion arose because the idea seems to have been conceived independently by both a Briton and a Frenchman in 1916.

It seems clear now that the first to do so was David Railton, a chaplain serving with the British Army on the Western Front. He later described how his inspiration came in August that year during a moving encounter with a rough wooden cross at Armentières in France, on which was inscribed ‘An Unknown British Soldier of the Black Watch’.

Chaplain David Railton, c1918 (Courtesy of the Railton family archive)

‘So I thought and thought and wrestled in thought. What can I do to ease the pain of father, mother, brother, sister, sweetheart, wife and friend? Quietly and gradually there came out of the mist of thought this answer clear and strong: “Let this body - this symbol of him - be carried reverently over the sea to his native land.”’Chaplain David Railton — 1931

Proposals

Just a few months later, in November 1916, Francois Simon, President of the Rennes Remembrance Society, proposed that the remains of an unidentified French soldier be interred in the Panthéon, the resting place of the great figures of French history. Because Railton initially kept the idea to himself, it was the French suggestion that entered circulation first.

This inspired a similar proposal by 'The Daily Express' in 1919, which was backed by the Comrades of the Great War Association. The idea was initially rejected by the British government, mainly on the basis that the Cenotaph had already by that time become established as Britain’s national war memorial.

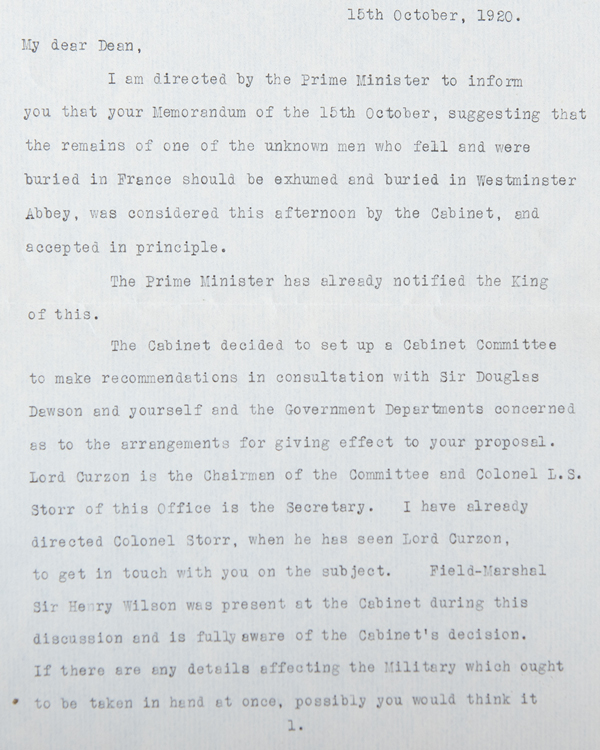

The idea may never have gained acceptance had Railton not belatedly taken action in August 1920. He wrote to Herbert Ryle, the Dean of Westminster, with the suggestion that a body be returned from the Western Front for burial in the Abbey. Ryle succeeded in getting the Prime Minster, David Lloyd George, and the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Field Marshal Sir Henry Wilson, to adopt the idea.

These men in turn won over both the Cabinet and the initially reluctant King George V. Wilson told the former that 'no words could tell how proud we officers and men would be to have one of our simple soldiers buried in Westminster Abbey’.

A warrior returned

In mid-October, a committee was hastily assembled to oversee the scheme. Plans were put in motion for a body to be returned from France for burial on Armistice Day (11 November), just three weeks later.

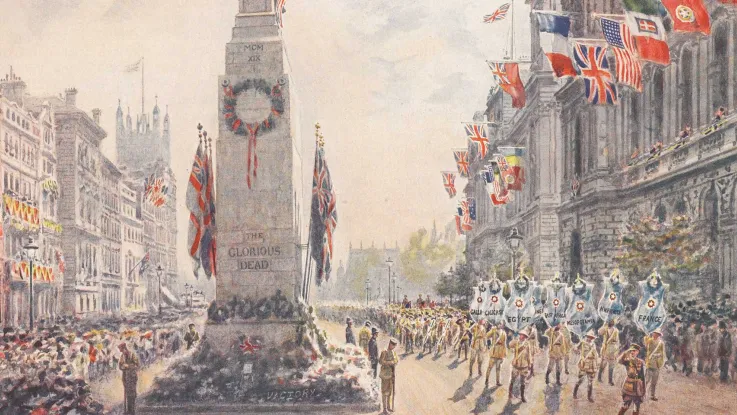

Despite the lack of time, everything went to plan. The Unknown Warrior was buried with great solemnity as part a dual ceremony which also saw the unveiling of the newly rebuilt Cenotaph.

After some debate over the appropriate location for their grave, the French finally chose the Arc de Triomphe over the Panthéon and made arrangements for a ceremony to take place the same day.

Letter to Dean Herbert Ryle, informing him the Cabinet had approved the burial of the Unknown Warrior, 15 October 1920 (By kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

An ‘Old Contemptible’?

Another source of confusion was discovered within the minutes of the Memorial Services Committee, the body set up by the government to plan the scheme. These contain the revelation that the chosen body was to be that of a man who died in 1914. The reason for this was a request from the Abbey authorities that the body needed to be fully decomposed, presumably to avoid interring a rotting corpse.

If carried out, this plan meant that the Unknown Warrior would most likely be a soldier of Britain’s pre-war regular army, known as the ‘Old Contemptibles’ in mockery of an insult made by Kaiser William II. While the government did issue a statement informing the public of this decision, they also included the dubious and contradictory assertion that the Unknown Warrior could be from one of the Dominion forces or be an airman or a sailor of the Royal Naval Division.

Significantly, the detail that the chosen man was a soldier of 1914 has largely been forgotten. By contrast, the idea that he could be any one of the British Empire’s missing has become a well-established part of the mythology.

An analysis of the methodology employed by the men who undertook the selection suggests that the truth lies somewhere in between. The Unknown Warrior was most likely British and not from the Empire, but it also seems likely that that he could have died at any point in the war and so was by no means certain to be an ‘Old Contemptible’.

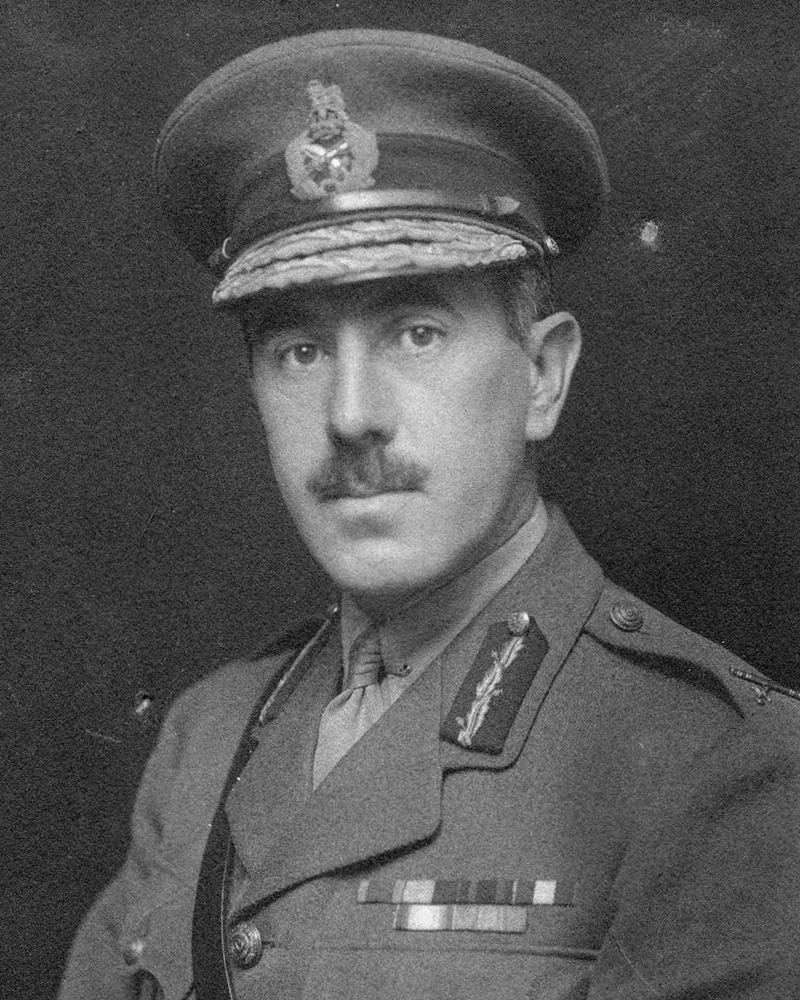

Brigadier General Louis Wyatt, 1923 (Courtesy of the Staffordshire Regiment Museum)

Selection

The most contentious part of the Unknown Warrior’s story concerns the mysterious selection process. This was undertaken in great secrecy by Army units based in France and Belgium. It involved the exhumation of a number of unidentified bodies from cemeteries situated in various battle areas along the Western Front. These were taken to a makeshift chapel at the Army’s headquarters at St Pol, near Arras, in northern France.

Here, the commanding officer, Brigadier General Louis Wyatt, made the final choice. No official record of how it was done was ever released, and so many different versions of this story have been told, and there are many long-standing disputes on points of detail.

Identity known?

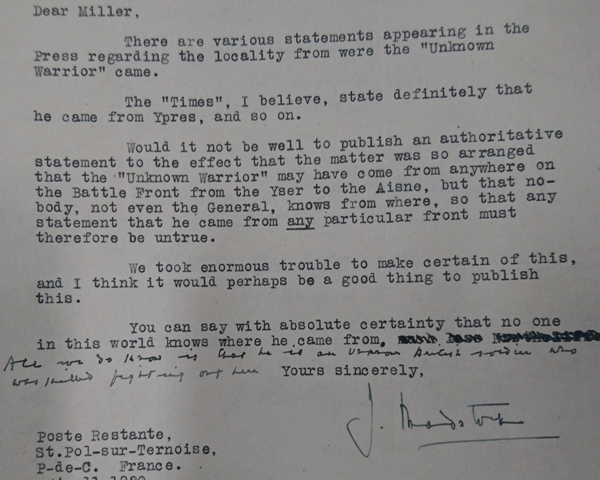

The most significant problem resulting from this secrecy was the persistent rumour in circulation during the inter-war period that the identity of the body was known in government circles. However, this is contradicted by the later accounts of the men involved, and the Unknown Warrior's anonymity is proven beyond dispute by one of the few surviving contemporary documents relating to the process.

This is a letter written by Colonel J Bradstock, an Army officer at St Pol at the time, to a colleague at the War Office. The letter concerns the inaccurate press speculation on the origins of the body, which Bradstock addresses by briefly outlining the selection method employed and giving his assurance that the body’s anonymity was preserved. He states: ‘You can say with absolute certainty that no one in this world knows where he came from.’

Selection date

One curious inaccuracy that crept into the story concerns the dates on which the selection took place. For many years, the dates of 7-8 November 1920 were used, as these had appeared in the most authoritative known account, which had been written by Wyatt for 'The Daily Telegraph' in November 1939.

This was challenged by Andrew Richards in his book 'The Flag: The Story of Revd David Railton and the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior'. Richards noticed that these dates did not square with what was known about the rest of the Unknown Warrior’s journey from St Pol to London.

The correct dates of 8-9 November have now been found on an earlier hand-written account by Wyatt kept at the Imperial War Museum in London, and have been corroborated by several other sources. These include a memoir held in the archive of the National Army Museum, written by Vere Brodie, who was serving at St Pol with Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps. Brodie did not witness the selection first-hand, but noted the dates and the timings of events, which accord with Wyatt’s earlier account.

Many of the personnel involved in the selection of the Unknown Warrior, 1920 (Courtesy of the Fitz-Simon Archive)

‘The hushed thrill in the camp all that day was marvellous.’Vere Brodie, QMAAC, describing the atmosphere at St Pol following the selection of the Unknown Warrior — 1920

How many bodies?

The longest-standing question surrounding the selection process concerns the number of bodies involved. Wyatt’s figure of four bodies conflicts with other accounts, notably that of Senior Chaplain George Kendall, which states that six were involved. Other plausible figures are three and five. This issue cannot be settled beyond dispute.

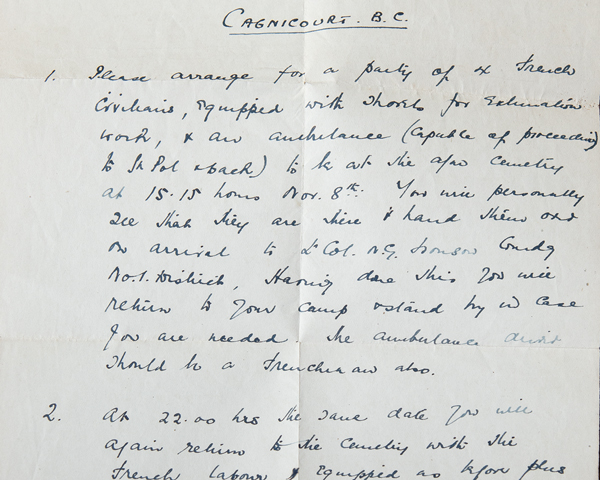

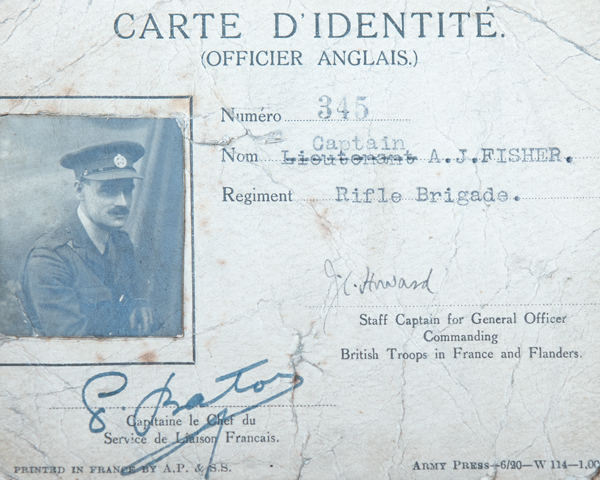

However, four remains the most likely figure, as it is backed up by two further important sources from participants: an account written by Major General Cecil Smith in 1978, and a set of secret orders issued to Captain Albert Fisher of 14 Graves Registration Unit on 6 November 1920. Significantly, while these sources are all in accord on this point, they diverge on what has become the most intriguing issue of all, the final resting place of the bodies which were not chosen.

Soldiers exhuming a body on the Western Front, 1919 (Courtesy of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission)

Officers involved in selecting the Unknown Warrior, including Captain Cecil Smith (second left), c1920 (Courtesy of the Fitz-Simon Archive)

Missing graves

Wyatt’s accounts state that the unselected bodies were buried in St Pol cemetery. This was first challenged by Smith, who wrote how he had been part of a team tasked with reburying them. He described how the original plan to bury them in St Pol was dropped because the appearance of three new graves there would have made it obvious that these were the men who had been involved in the selection, and this would have been detrimental to the secrecy surrounding the process.

Instead, Smith described how his team reburied them 50 miles away along the Albert-Bapaume road. It was their hope that these graves would be discovered by body search parties working in that area and would then be reburied, completely anonymously, elsewhere.

Smith also related how he later checked the burial records, which stated that three bodies from that area had indeed been discovered and reburied, although it is not known where. Smith’s version was seemingly confirmed by the grave records of St Pol cemetery, which show that the last burial to have taken place there was in July 1920.

Secret orders issued to Captain Albert Fisher, 14 Graves Registration Unit, 6 November 1920 (By kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

Identity card issued to Captain Albert Fisher, 1920 (By kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

Alternative location?

However, Smith’s version has now itself been challenged by the secret orders that were issued to Captain Fisher. These state that the three remaining bodies were to be interred in Cagnicourt cemetery. As these orders are a contemporary document, written just two days before the selection was made, they carry significant weight.

However, while records also show that Fisher and his team were working in Cagnicourt around that time, an analysis of the graves there has found none that match these bodies. This leaves Smith’s account as the most plausible, though there remains plenty of scope for doubt.

So, while some of the questions surrounding him can be settled satisfactorily, it would seem that the Unknown Warrior is not yet ready to yield all of his secrets.

The grave of the Unknown Warrior, Westminster Abbey, c2019 (By kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster)

The Unknown Warrior's grave in Westminster Abbey, c2019 (By kind permission of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster)