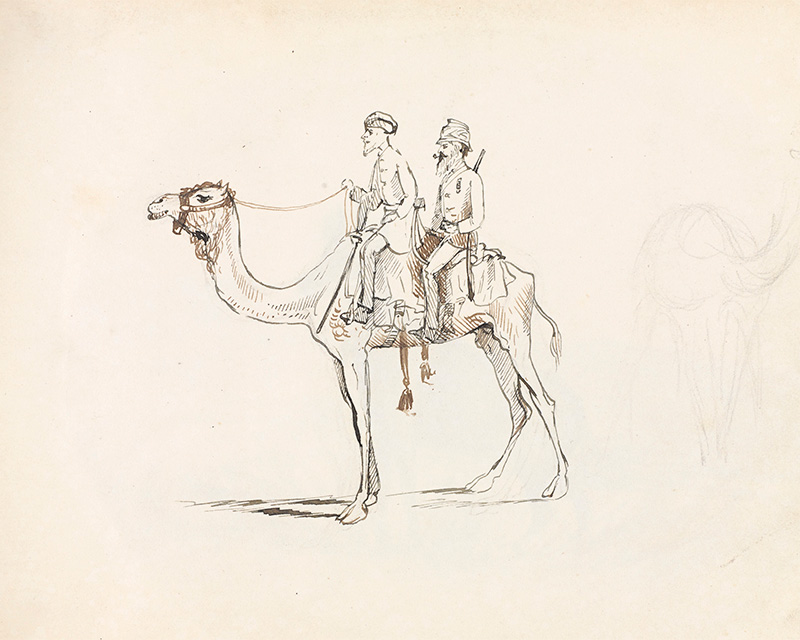

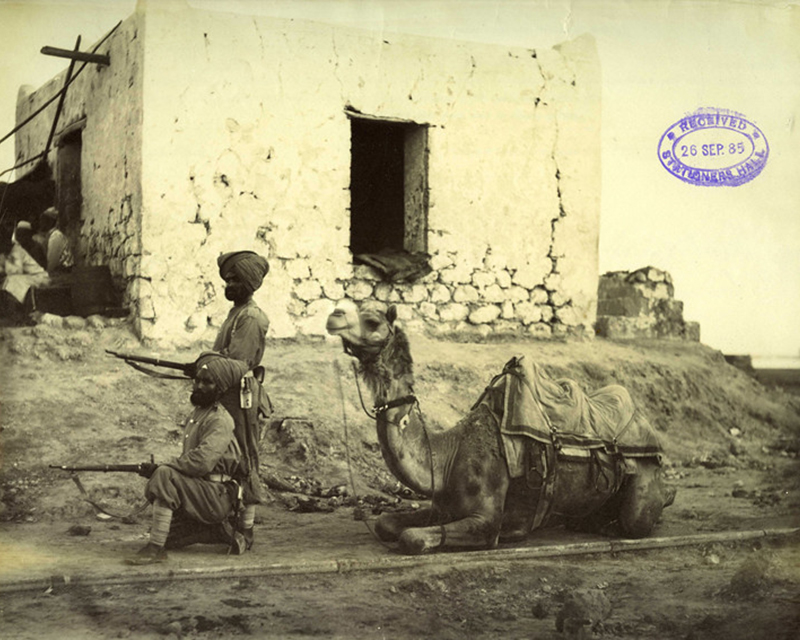

Study of a British soldier with two camels, Egypt, c1885

A case for camels

For millennia, camels have been vital beasts of burden in areas of the world with large expanses of arid terrain. They can travel long distances with heavy loads and are very well adapted to hot, dry conditions.

Their military use also dates back thousands of years. The Romans recruited camel-mounted soldiers - ‘dromedarii’ - for service in their eastern imperial provinces (much of today’s Middle East). In doing so, they were adopting local practices that had been used in these regions for centuries beforehand.

Army adaptation

As Britain’s global interests and influence expanded during the 17th and 18th centuries, its armies had to adapt to new climates and conditions. They also had to grow accustomed to the resources available in different parts of the world.

By the 19th century, the one-humped Arabian camel, or dromedary, had become an essential pack animal both for the British Army and the Indian Army on operations in Asia and northern Africa.

As well as carrying supplies, camels transported troops across territories where they were better suited to the terrain, or more easily procured, than horses. On campaign, they were used for reconnaissance, delivering messages and carrying infantry soldiers into combat zones.

Riding a camel presented different challenges to riding a horse. Sourcing and caring for these animals also required different knowledge and expertise. As more time was spent among communities with long histories of working with camels, lessons were gradually learned about how much to feed, water and rest them, and which types of camel were better suited to which roles.

‘If a camel yawns, it shows he is about to go on a long journey. If a camel roars without reason in a melancholy way, it will either be taken away by thieves or will have to go to a distant place. A vision of a camel in a dream is considered a good omen.’Excerpt from 'Camel Breeding and Camel Management in Baluchistan' — 1908

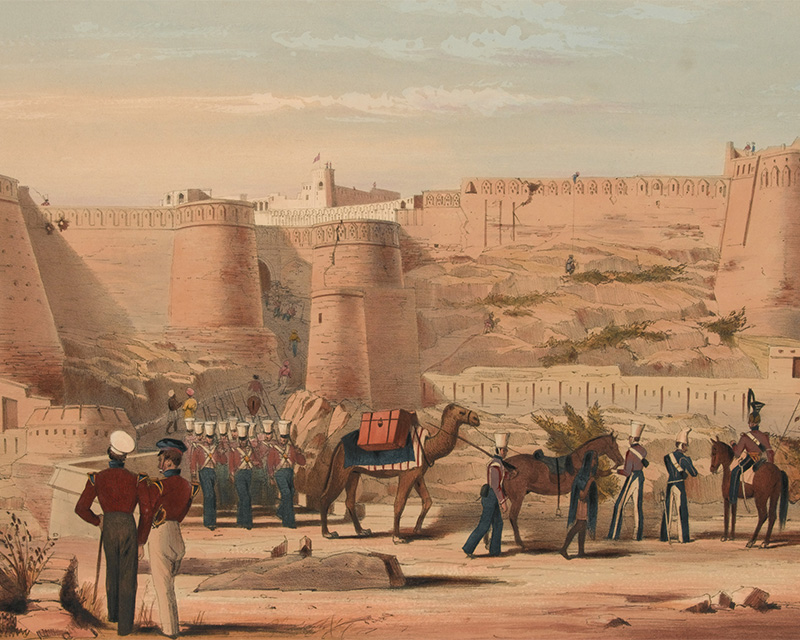

First Afghan War

Camels were used by armies operating along the northern frontiers of British India throughout the 19th century. While sometimes tasked with pulling heavy artillery pieces, they were mainly used as pack animals - carrying loads on their backs. This was a major asset when crossing rugged terrain, where carts or wagons were less viable.

During the First Afghan War (1839-42), around 30,000 camels accompanied the Army of the Indus, carrying general supplies and soldiers’ personal possessions. They were also formed into camel batteries and worked in tandem with horse artillery to transport guns to the front line.

Scinde

Soon after the First Afghan War ended, Major General Sir Charles Napier was sent to Scinde (now Sindh, a province in south-east Pakistan) to consolidate British control in the region.

In January 1843, soldiers of the 22nd Regiment of Foot survived a punishing foray into the desert, riding two men to a camel. Later that year, the Scinde Camel Corps was formed to patrol the newly conquered territory and help keep the peace.

‘Brigadier General Arnold of the Army of the Indus… breathed his last at [Kabul] shortly after our arrival there… [H]is effects were publicly sold at auction a few days after. The General had left Bengal with about eighty camels laden with baggage and necessaries, of which about five and twenty remained at the time of the sale.’Extract from ‘Scenes and Adventures in Affghanistan’ by William Taylor — 1842

Indian Rebellion

The military use of camels in India was not confined to the northern frontiers. During the Indian Rebellion (1857-59), their use as pack animals extended to transporting reinforcements to the besieged city of Delhi in pannier-style baskets, known as kajawahs.

In the latter stages of the campaign, soldiers from various British regiments rode camels as they pursued remnants of rebel groups across the countryside. To assist with this endeavour, a Camel Corps was formed in April 1858 from detachments of the Rifle Brigade. Each camel carried a soldier accompanied by an Indian ‘driver’. The unit was later strengthened with the addition of 200 Sikh troops, but was disbanded in 1860.

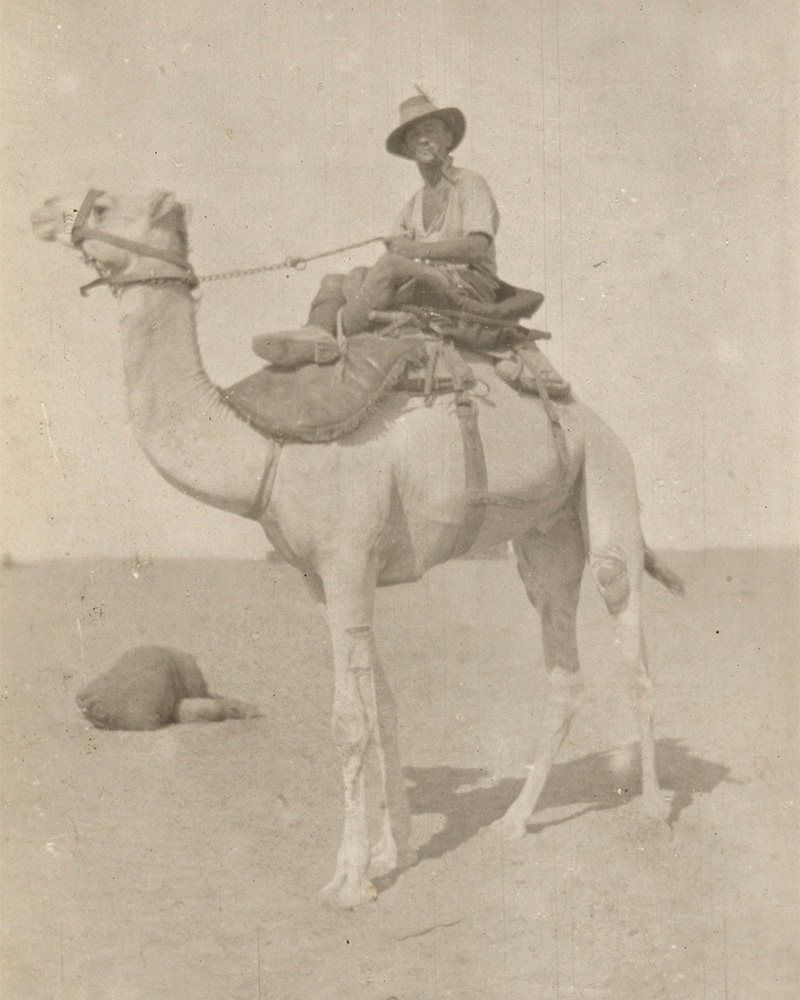

Nile Expedition

In 1884, another Camel Corps was formed in Egypt as part of the expedition sent to rescue General Charles Gordon, the Governor-General of Sudan, who had been overwhelmed by a local uprising. It consisted of four camel-mounted units: the Guards Camel Regiment, the Heavy Camel Regiment, the Light Camel Regiment and the Mounted Infantry Camel Regiment.

Unlike cavalrymen, the soldiers of the Camel Corps were expected to fight on foot. They only remained in the saddle during their marches across the desert. During combat, a soldier would dismount and tie his camel’s front legs together so that it didn’t need tending.

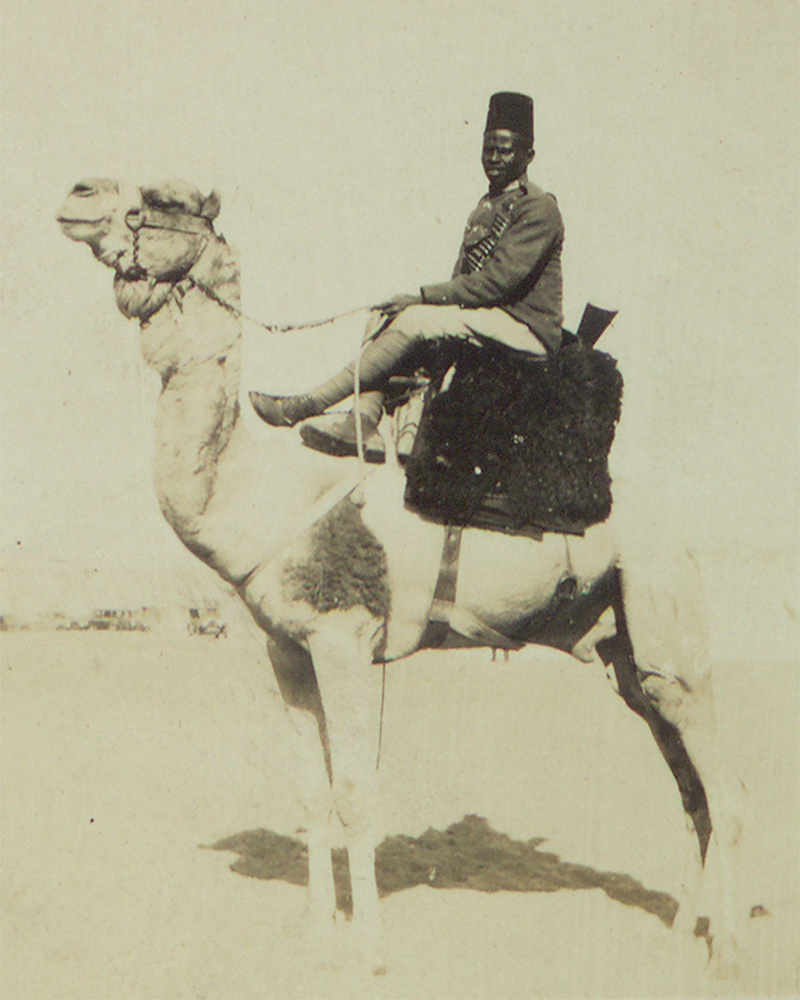

The Gordon relief expedition was a failure, but the British succeeded in reconquering Sudan in 1899. The Camel Corps continued to operate there as a single unit, mainly composed of Egyptian and then Sudanese troops. It later became part of the Sudan Defence Force, serving during the Second World War (1939-45) and remaining under British command until Sudan’s independence in the 1950s.

Camel Corps at the ready, c1884 (Photograph by Felice Beato, courtesy of The National Archives (via Flickr))

Lady Butler

The painting below, which is now on display in Soldier gallery, depicts a British soldier with two camels. It was produced by Lady Elizabeth Butler during a visit to Egypt in 1885. Her husband, Lieutenant General William Butler, was based at Wadi Halfa, a British garrison on the Egypt-Sudan border, from where the relief force had set out.

The painting is thought to be a study for 'A Desert Grave: The Nile Expedition, 1885', which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1887, but has since been lost. The sombre title perhaps refers to the failure of the expedition and the resulting death of General Gordon.

Lady Butler later complained that the conditions she had encountered in the Egyptian desert were not particularly conducive to her artistic pursuits.

‘While at Halfa I made many sketches in oil for my picture “A Desert Grave” out in the desert across the river. It is very trying painting in the desert on account of the wind, which blows the sand perpetually into your eyes. With that and the glare, I took two inflamed eyes back with me to Europe. The picture should have been more poetical than it turned out to be, and I wish I could repaint it now.’Extract from Lady Butler’s autobiography — 1922

Imperial Camel Corps

During the First World War (1914-18), the Imperial Camel Corps (ICC) was formed - initially from Australian infantry soldiers - to help suppress the Senussi Revolt in Egypt's Western Desert. In December 1916, the ICC was organised into a brigade to support the wider war effort against Ottoman forces in the region.

The Imperial Camel Corps Brigade included four camel-mounted infantry battalions, drawn from British, Australian and New Zealand forces. Indian soldiers provided artillery support as part of the Hong Kong and Singapore Mountain Battery.

During the campaign in Egypt and Palestine (1916-18), camels from the brigade’s support units carried supplies, weapons and ammunition. They also operated as a makeshift ambulance service, transporting wounded soldiers.

Additionally, the Camel Transport Corps helped to keep British and Commonwealth forces supplied throughout the campaign. Around 170,000 Egyptian volunteers along with 72,500 camels transported water, as well as food and medical supplies, to the front.

The ICC was disbanded at the end of the First World War. Its mounted units had already started converting to horses as operations moved away from desert terrain in the summer of 1918. Australian and New Zealand companies reorganised as the 5th Light Horse Brigade.

Mechanisation

Rapid technological advancements in the early 20th century saw motorised vehicles take over many tasks that had previously required camels (and other animals). Even so, there were still environments where camels remained the Army’s preferred choice.

Just as the Sudanese Camel Corps continued to defend Britain’s overseas interests, similar contributions were made by the Somaliland Camel Corps and the Bikaner Camel Corps right up to the Second World War.

Difficulties

Despite their many merits, camels undoubtedly had their faults. They could be difficult to handle, which perhaps explains why they were preferred for mounted infantry rather than cavalry roles. They also had a reputation for bad breath and a tendency to bite.

General Sir Garnet Wolseley, an influential 19th-century Army reformer - and the commander of the Nile Expedition (1884-85) - reported in the fourth edition of his ‘Soldier’s Pocket Book’ (1882): ‘[Camels] are extremely delicate in constitution, and liable to diseases little understood. When suffering from over-work they do not recover with rest like horse or mule: they pine and die away.’

Oonts

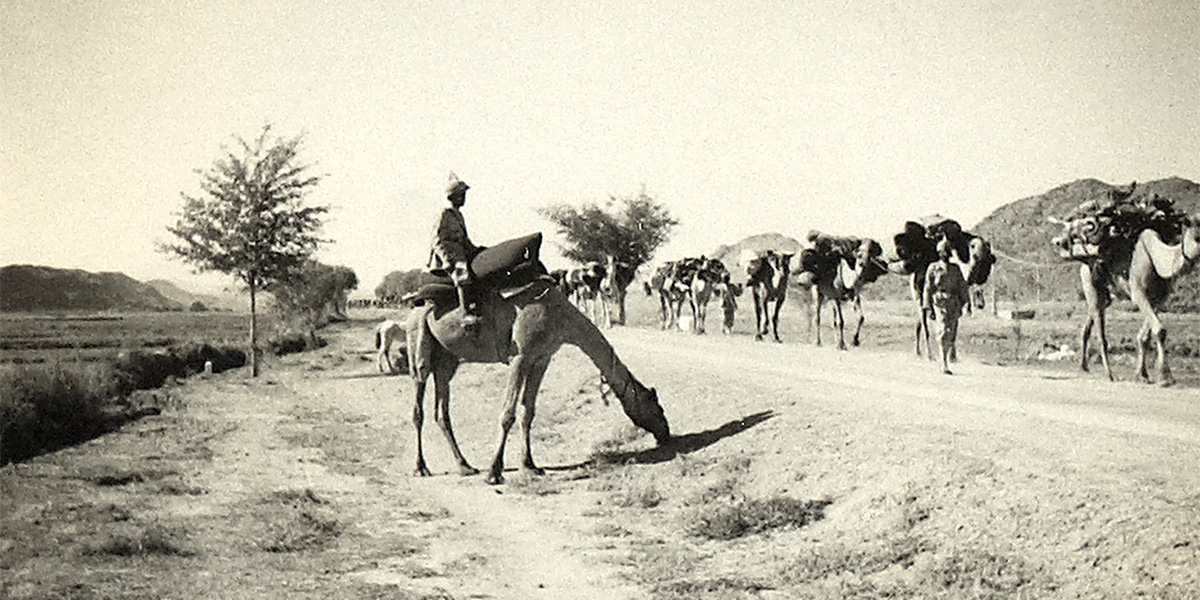

The caption on the photograph above, depicting Indian Army pack camels in 1930s Waziristan, is taken from Rudyard Kipling's poem, 'Oonts'. The title of the poem is a derivation from the Hindi word for camel.

Subtitled 'Northern India Transport Train', the poem catalogues the failings of ‘the commissariat camel’, comparing it with some of the other working animals in army service. The Commissariat was a 19th-century precursor of today's Royal Logistic Corps, responsible for the smooth running of the Army’s supply chain.

The ’orse ’e knows above a bit, the bullock’s but a fool, / The elephant’s a gentleman, the battery-mule’s a mule; / But the commissariat cam-u-el, when all is said an’ done, / ’E’s a devil an’ a ostrich an’ a orphan-child in one. / O the oont, O the oont, O the Gawd-forsaken oont! / The lumpy-’umpy ’ummin’-bird a-singin’ where ’e lies, / ’E’s blocked the whole division from the rear-guard to the front, / An’ when we get him up again - the beggar goes an’ dies!Excerpt from ‘Oonts’, a poem by Rudyard Kipling — 1890

See it on display

Come and see Lady Butler’s ‘Study of a British soldier with two camels’ in our Soldier gallery. You’ll find it displayed alongside a selection of other items showcasing the important working relationships between serving soldiers and animals.