Army photographers

As soldiers first and foremost, Army photographers deploy with units to front lines and training areas around the world. They are the eyes of the Army and enjoy an unrivalled view of life at the heart of the action.

The British Army photographic branch sits within the Royal Logistic Corps. It selects candidates from various ranks and service backgrounds, who then undergo intensive training in capturing both still and moving images.

As well as documenting day-to-day activities at home, Army photographers embed themselves within front-line units to record life on operation, both in camp and out on task. They also provide specialist photographic training to a variety of other departments and regiments.

Since 1975, the Army Film and Photographic Competition has showcased the best work of today's military photographers. It recognises their contribution both to operational success and to the recording of soldiers’ service for posterity.

Pioneers

But military photography is not a new phenomenon. From its earliest days, photography has been used to document the places and people the Army has encountered around the world.

The National Army Museum’s collections are rich in images taken by early photographers who accompanied the Army on operations. Some were civilians 'embedded' with the military, while others were serving soldiers.

Their combined efforts have left a unique resource for anyone interested in the earliest years of photography or in mid-19th century British Army and imperial history.

The origins of photography

Photography emerged in the first half of the 19th century from a fusion of the technology of the centuries-old 'camera obscura' and experimentation with light sensitive chemicals such as silver nitrate.

The first permanent photograph was taken by the French inventor Joseph Niépce. But the chief technical breakthroughs were made by Louis Daguerre (1839) and Henry Fox Talbot (1840). Their rival methods - the daguerreotype and calotype - competed for pre-eminence during the 1840s.

Both of these methods were superseded by Frederick Scott-Archer’s wet-plate or wet-collodian method of 1851. This had the combined virtues of improved quality and reproducibility and so helped the practice of photography to flourish.

However, wet-plate photography still had the major drawback of requiring photographers to take their darkroom with them wherever they went. And cameras remained bulky and cumbersome. Photographs also required lengthy exposure times, preventing the production of any action shots.

All of these factors hindered the practice of outdoor photography and were major constraints upon pioneering military photographers.

The imperial context

The emergence of photography coincided with the early years of Queen Victoria's reign, and it was increasingly employed in Britain's imperial endeavours.

The Indian subcontinent, for example, became an attractive subject for photographers, who were keen to demonstrate to people at home the wonders of Britain's dominions in the east.

Most of the photographers who worked in India in the 1840s and 1850s were British subjects. They were the soldiers, engineers, merchants and civil servants who conquered, surveyed and governed huge tracts of land.

The East India Company actively encouraged its employees to photograph India, to record its archaeological sites, its places of scientific interest and its ethnic diversity.

Much of the work put together by these individuals came back to Britain, with some finding its way into public collections. At a time when museums were growing in popularity, the leading photographers became well-known, displaying and selling their images at large exhibitions.

John McCosh

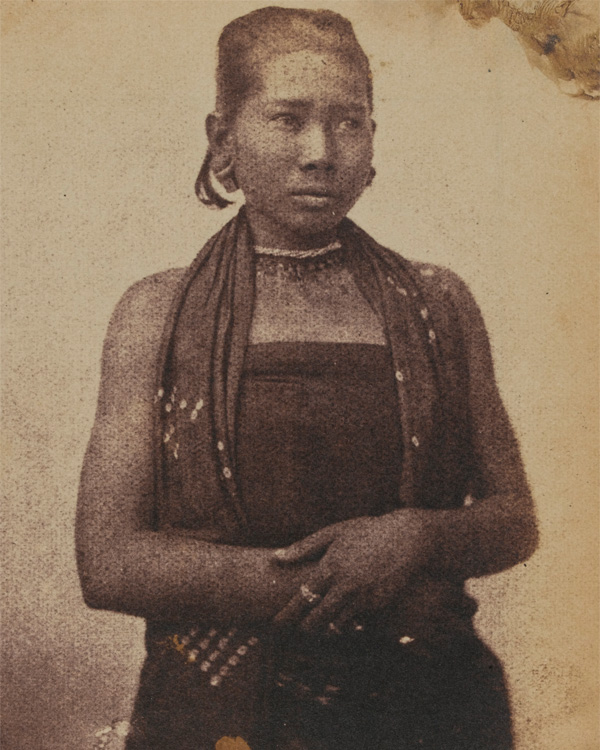

John McCosh (1805-85) was a pioneer of both military photography and the photography of south-east Asia. During his service as a surgeon with the Bengal Army in the Second Sikh War (1848-49) and the Second Burma War (1852-53), he succeeded in taking a remarkable series of calotype pictures which are among the earliest military photographs in existence.

Limited at first to portraiture, his work illustrates his wide-ranging interest and artistic eye, with subjects including British military personnel and their families, as well as local people.

As his skill improved, he was able to include larger landscape and architectural photographs. While in Burma (Myanmar), he took pictures of many of the splendid buildings in Prome (Pyay) and Rangoon (Yangon).

War reporting

In the mid-19th century, higher literacy rates and new technology, like the telegraph, led to a growing demand for accurate, up-to-date news from around the globe.

The outbreak of the Crimean War (1854-56) helped 'The Illustrated London News' double its readership from 100,000 to 200,000 per week. By November 1854, it had become the most popular newspaper in Britain.

Improved distribution by railway and cheaper printing methods saw the market for newspapers go from strength to strength. And as printing processes improved further, photographs took over from drawn illustrations as the preferred medium for depicting topical events.

Roger Fenton

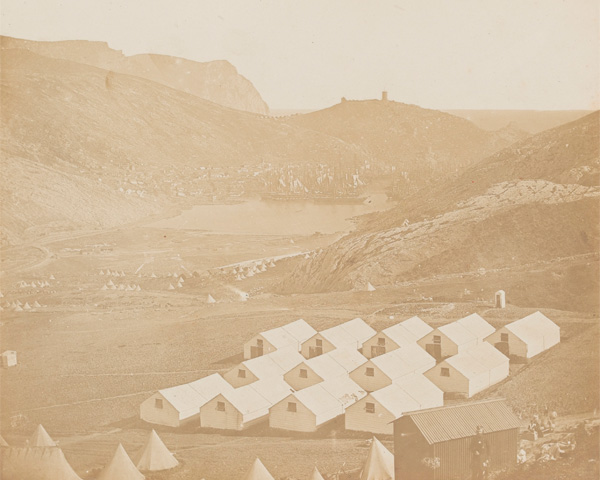

Roger Fenton (1819–69) was a founding member of the Royal Photographic Society in Britain. He enjoyed a short but varied career and is best remembered for his pioneering work as a photographer of the Crimean War (1854-56).

Although compromised by the influence of his commercial and official patrons, and by the difficult working conditions of the Crimea, his photographic record of this conflict is truly remarkable in its quality and diversity.

His pictures range from portraiture through to landscapes and notably include 'tableau vivant' (living picture) compositions, in which figures have been carefully posed in a dramatic and theatrical manner.

James Robertson

James Robertson (1813-88) was superintendent and chief engraver to the Imperial Mint of the Ottoman Empire and established a reputation as an architectural and war photographer.

He produced and sold albums of photographs of the cities of the eastern Mediterranean, which he toured extensively. He also produced a series of photographs of the Crimean War.

Robertson specialised in landscape shots and notably produced many fine views of the Crimean scenery. He was present at the end of the siege of Sevastopol and captured the destruction and chaos of war with his gloriously detailed images of the devastated forts.

Felice Beato

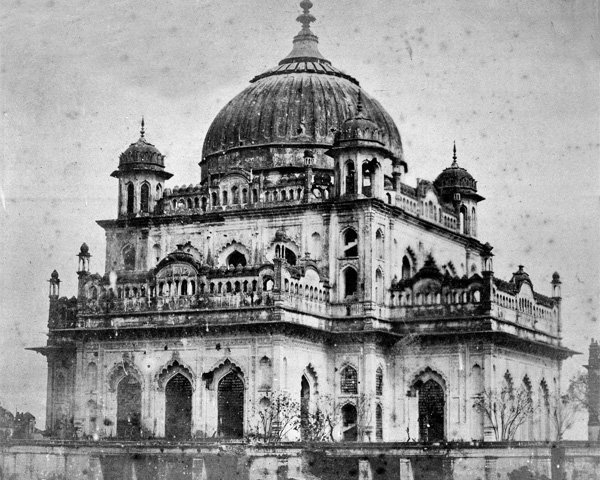

A British citizen of Italian parentage, Felice Beato (1825-1909) was another early war photographer of great importance. He travelled extensively during his career, notably visiting India, China, Korea and Japan, bequeathing to posterity many of the earliest photographic images from these countries.

His remarkable pictures of the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny in 1858 and the China War in 1860 feature some of the earliest photographs of corpses and skeletal remains.

Although groundbreaking in its graphic depiction of war, Beato's work raises important questions regarding the motives and role of the war photographer. Rather than exciting sympathy and compassion, his dramatic images of the victims of war could easily be taken for macabre voyeurism. They could also be interpreted in an imperialistic light, glorifying the power of British arms.

EW Jones

Little is known about Lance Corporal Jones of the Royal Engineers (RE), but he is one of the more interesting pioneers of Indian photography.

Although most early military photography seems to have been carried out by off-duty officers, or civilians accompanying the Army, the Royal Engineers and its equivalents in the East India Company appear to have been introducing the new technology to both officers and NCOs by the mid-1850s.

From 1855, tuition in photography was available to cadets at the Company's college at Addiscombe. And by 1858, at least one RE unit - the 23rd - used the camera as a standard part of its equipment.

Colonel Faber, Chief Engineer in Madras in 1855, was in no doubt as to the value of the camera, even in untrained hands. He believed it would soon supersede 'the tedious and highly paid labours of the professional draughtsman', and that, in time, knowledge of the medium would form part of the duties of all engineers.

During the Indian Mutiny, Jones produced a handful of albumen prints from collodion negatives, most of which were of Lucknow during and after its recapture in March 1858. He seems to have been the only photographer to record the scenes at the time of the actual fighting, whereas individuals like Beato took their photographs after the event.