A hero’s death

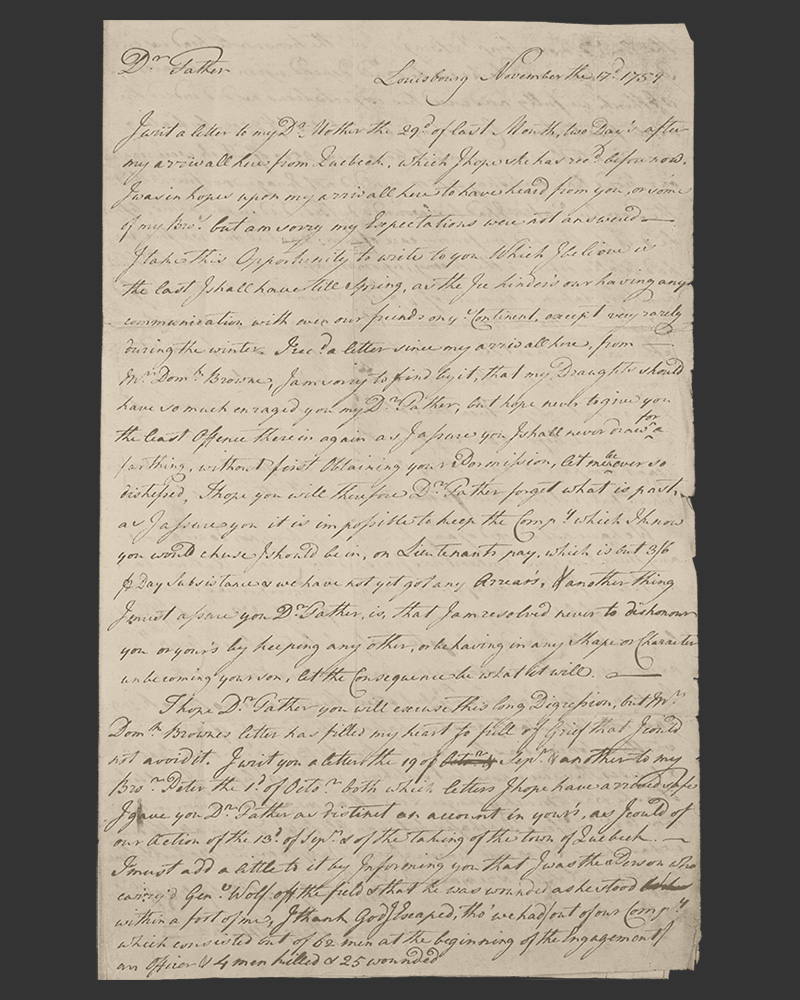

One of the most famous deaths in British military history was that of Major General James Wolfe at the Battle of Quebec on 13 September 1759. Wolfe fell at the moment of triumph during this crucial engagement of the Seven Years War (1756-63), which brought about the final defeat of the French in North America.

This epic story of death and glory transformed Wolfe into a national hero. It was captured in one of the most famous paintings of the era, ‘The Death of General Wolfe’ (1770) by Benjamin West, which presents the fatally stricken commander, surrounded by his officers and men, and an indigenous American ally.

However, West is known to have used considerable artistic licence when creating this scene. Among many inaccuracies is the fact that most of the men depicted were not actually there. The only person in the painting who was in fact present was Lieutenant Henry Browne of the 22nd Regiment of Foot and Louisbourg Grenadiers. Although not mentioned in the painting’s key, he is believed to be the man standing behind Wolfe, holding the Union Flag aloft.

Browne was one of four men known to have attended the wounded general as he lay dying. He recounted this profound experience in a letter to his father written a few months later. This is one of the earliest ‘death’ letters in the Museum’s collection.

‘The Poor Genl [General] after I had his wounds dressed, died in my arms, before he died he thanked me for my care of him, & asked me whether we had totally defeated the enemy, upon my answering him we had killed numbers, taken a number of officers & men prisnr [prisoner] he thanked God & begged I would then let him die in peace. He expired in a minuet [minute] - afterwards, without the least struggle or groan. You can’t imagine Dr [dear] Father the sorrow of every individual in the army for so great a loss, even the soldiers dropt [dropped] tears, who were but the minuet before driving their bayonets through the French. I can’t compare it to anything better, than to a family in tears & sorrow which had just lost their father, their friend & their whole Dependences.’Letter from Lieutenant Henry Browne to his father, John Browne, recounting the death of Major General James Wolfe, addressed from Louisbourg — 17 November 1759

Forgotten men

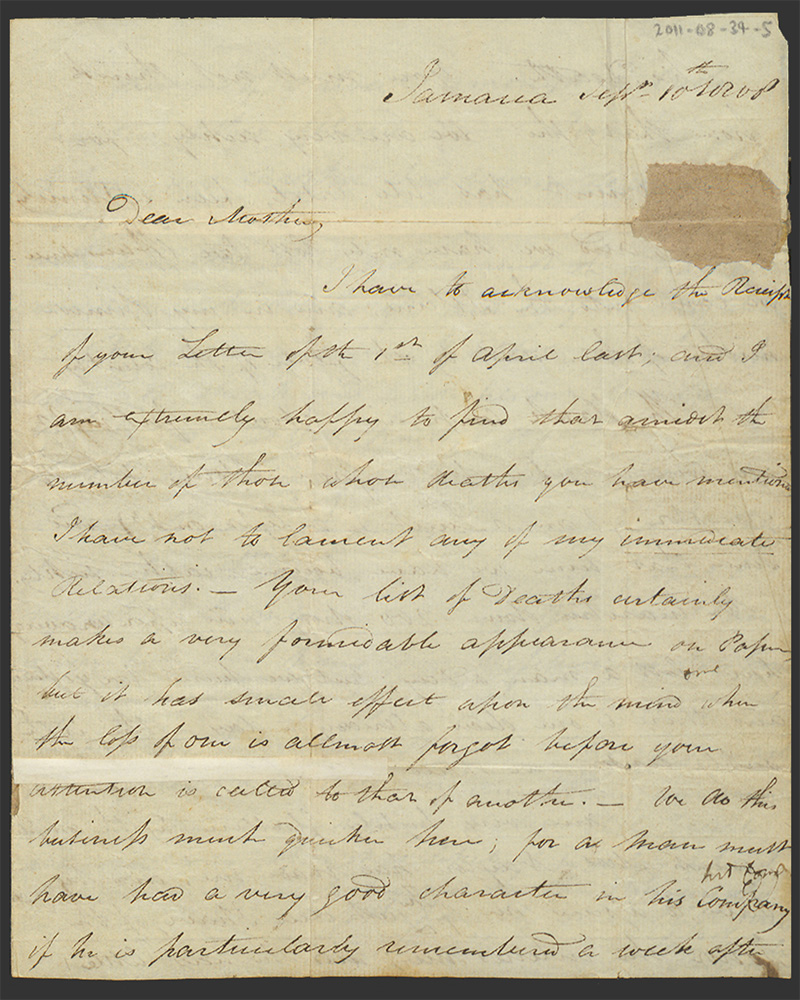

Not all soldiers experience a glorious death in battle. This was especially true of troops stationed in tropical regions, such as the West Indies, where they were ravaged by disease and often died forgotten men.

This is strikingly revealed in a letter written by Lieutenant Edward Teasdale of the 54th (West Norfolk) Regiment to his mother during his service in Jamaica in the early 1800s:

‘I have to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 1st of April last, and I am extremely happy to find that amidst the number of those whose death you have mentioned I have not to lament any of my immediate relations - your list of deaths certainly makes a very formidable appearance on paper but it has small effect upon the mind [here] when the loss of one is almost forgot before your attention is called to that of another. We do this business much quicker here; for a man must have a very good character in his company if he is particularly remembered a week after his death... we marched down 200 strong and upon average have lost a man a day, but we buried two yesterday and there is one dead already to day.’

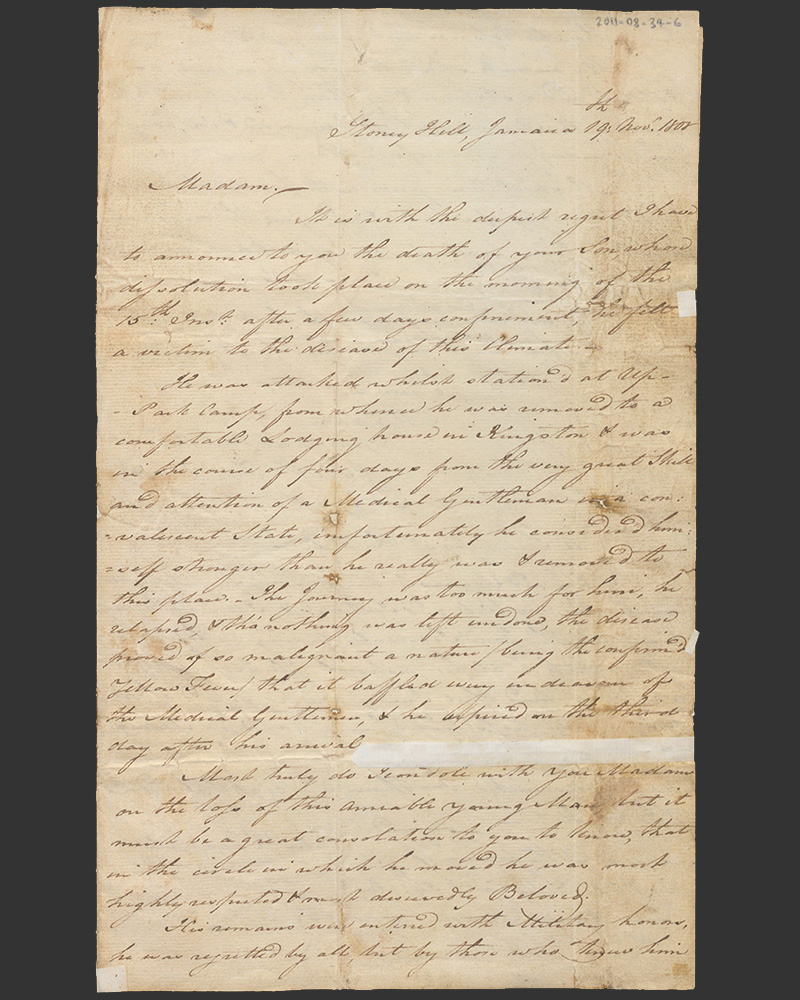

Letters of condolence

Teasdale himself was to fall ill and die just a few months later. His commanding officer, Major Robert Frederick, undertook the sombre task of writing to Teasdale’s mother to inform her.

Major Frederick’s letter is an early example of the type of condolence letter that has been written by many commanding officers and chaplains in accordance with their duty to the families of the fallen. Written in full knowledge of the impact that they would have upon the recipient, these letters can be heartfelt and deeply moving.

‘Most humbly do I console with you madam on the loss of this amiable young man, but it must be a great consolation to you to know, that in the circle in which he moved, he was most highly respected [and] most deservedly beloved.’Letter from Major Robert Frederick, 54th (West Norfolk) Regiment of Foot, to Mrs Jane Teasdale, informing her of her son Edward’s death, Stony Hill, Jamaica — 19 November 1808

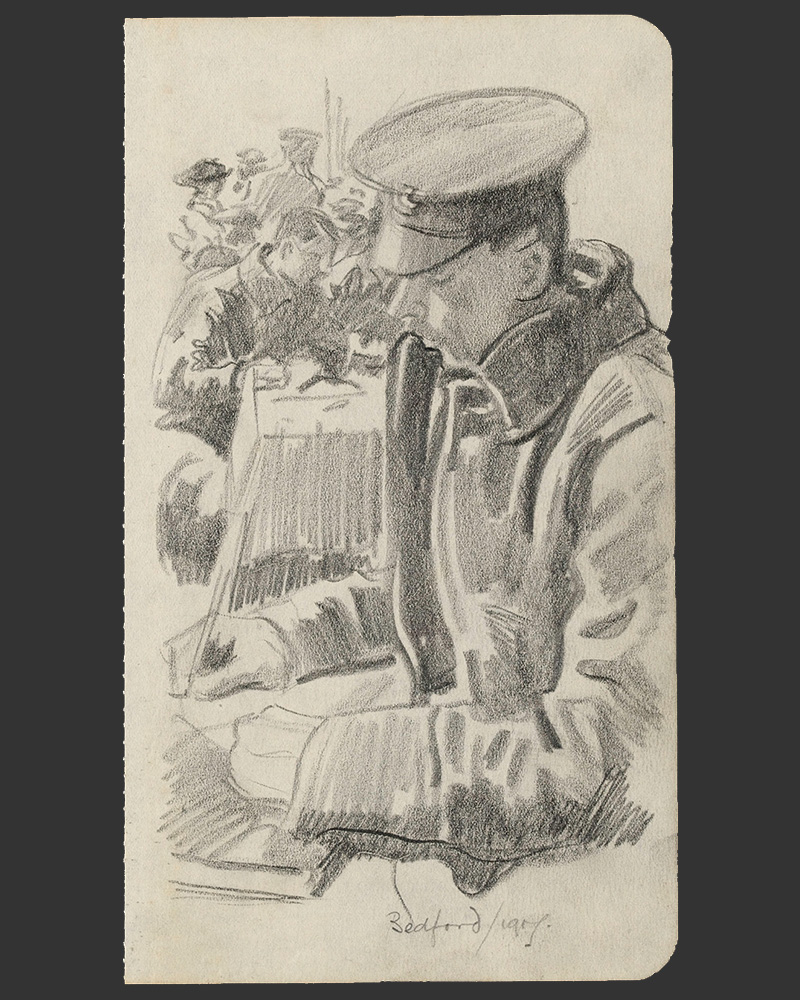

A heavy burden

However, writing such letters could place a heavy strain upon those frequently called upon to do so. This burden is revealed in the diary of Father Francis Gleeson, a chaplain who served with the Royal Munster Fusiliers during the First World War (1914-18). He wrote:

‘I got 12 letters today... What answering they will take tomorrow. I like to give these poor people all the solace I can, anyhow, but still there’s no limit to the sorrowing inquiries. The tragedy of these letters.’

In such circumstances, officers often sought to remain emotionally detached. Consequently, their condolence letters could sometimes be contrived, formulaic and even misleading. To bring comfort to the bereaved, the fallen soldier’s good character, bravery and popularity were usually emphasised. The suffering that they may have endured was correspondingly downplayed.

Family and friends

Far more candid are letters exchanged between family and friends. These often contain a welter of strong emotions. Anger and bitterness are commonplace. But many also contain more tender sentiments, as fond memories of the deceased are recalled.

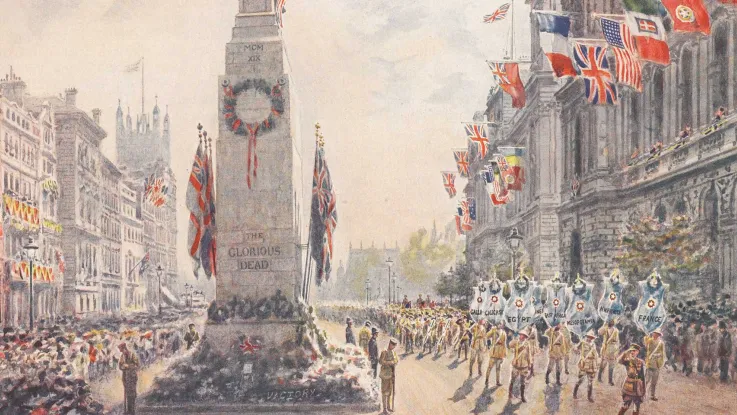

Among the saddest examples in the Museum’s collection are letters exchanged between the family of Second Lieutenant Noel Evans of the Royal Artillery. Evans died of his wounds on 11 November 1918, just as the Armistice bringing an end to the First World War was being signed.

A letter from his mother, Violet, to her sister reveals how the tragedy of Noel's passing was deepened by the widespread celebrations that accompanied the news of peace and victory.

‘To think that we shall never see his dear smile again. It’s all been so cruelly hard... all the horrible noise and crowds and rejoicing everywhere day and night, it has been a continuous nightmare and the journey back I thought never would come to an end. It was such an awful shock when we got there to be told he had already gone to the cemetery… I don’t know how to face life without him.’Letter from Violet Evans to her sister, Eve — 16 November 1918

Fathers and sons

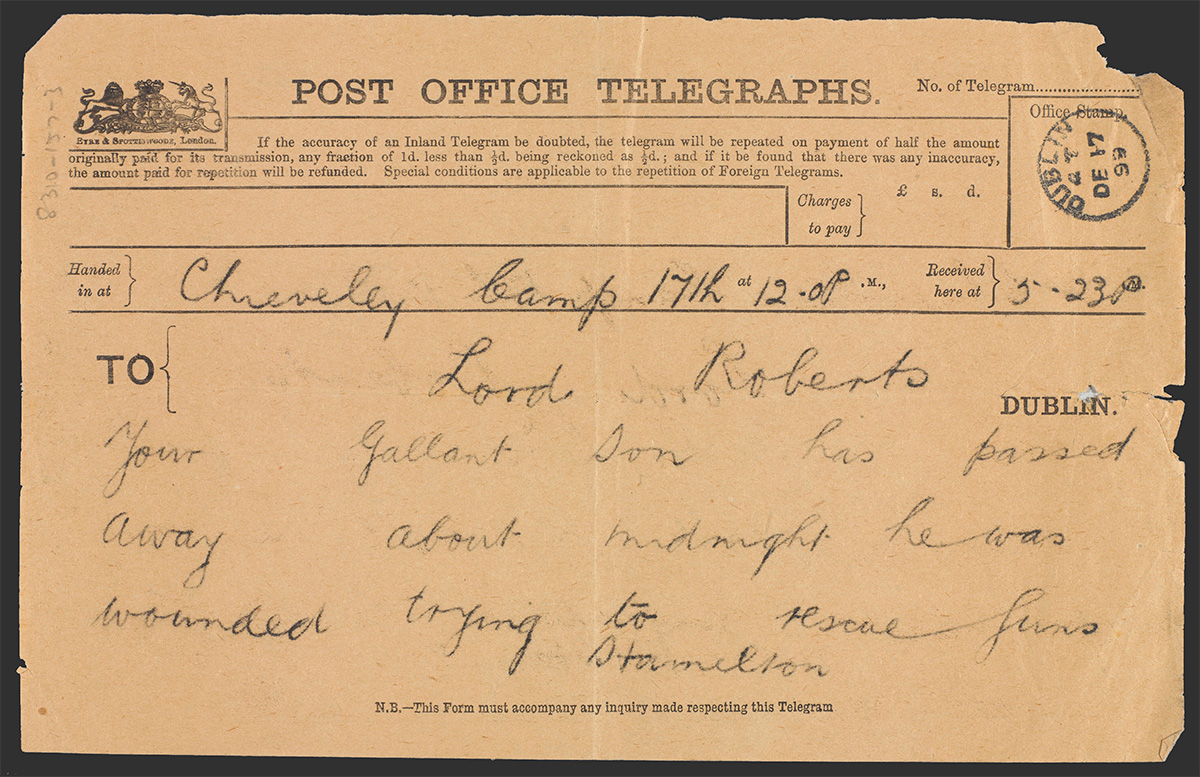

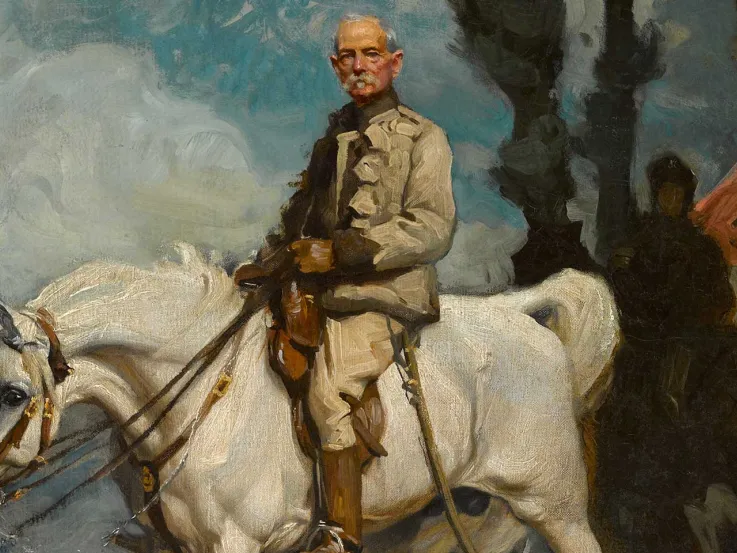

Another intimate collection of correspondence on this theme relates to the death of Lieutenant Frederick Roberts of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Roberts was the only son of Field Marshal Lord Roberts and the first person to be awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross (VC) after being fatally wounded in action at Colenso during the Boer War (1899-1902).

A telegram conveying this dreadful news was delivered to Lord Roberts by his friend, Lord Landsdowne, Secretary for War. Landsdowne had recently informed Roberts that he was to take up the position of commander-in-chief in South Africa, following Britain’s early reverses in the fighting there.

Lansdowne later wrote of this encounter to Roberts’s daughter Lady Aileen, a letter which provides a rare glimpse into how the news of a death was received:

‘I had to go and find your father and break the news to him... The blow was almost more than he could bear, and for a moment I thought he would break down, but he pulled himself together. I shall never forget the courage which he showed, or the way in which he refused to allow this disaster to turn him aside from his duty.’

The subject of Frederick’s demise was revisited by Landsdowne in a letter he wrote to Lord Roberts on 2 November 1914, a few months after the outbreak of the First World War, and just a few days before Roberts’s own death. Significantly, it was written in response to a letter of condolence that Roberts had himself sent following the recent death of Landsdowne’s son, Charles, during the fighting on the Western Front.

‘Of the many kind letters which I have received none has touched me [more] than yours – I am sure you know why. I have never forgotten that evening when it fell to my lot to tell you [about] Freddy’s death – nor can I ever forget the courage & resignation with which you bore the blow – a blow heavier in a way than mine for I have a son left to comfort me... He is gone & our lives can never be the same but nothing can rob us of the precious memories which we shall cherish so long as we are here.’

Cry for help

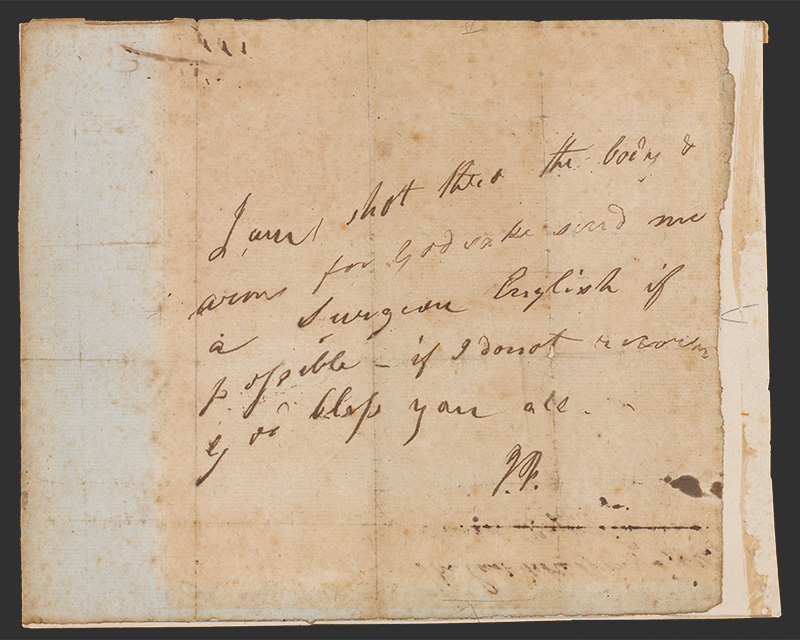

Just as compelling are letters that are known to be the last words written before their author's death. The most extraordinary and macabre example in the Museum’s collection is the final note left by Captain Joseph Fenwick of the 3rd (The East Kent) Regiment of Foot (The Buffs). This was written in his own blood after he had been mortally wounded near Alcobaça in Portugal during the Peninsular War (1808-14).

Although brief, the note speaks volumes of the horrible plight in which Fenwick found himself, being seriously wounded and cut off from all medical care. Addressed to his commanding officer, Colonel Richard Blunt, it is a desperate cry for help from a dying man.

‘I am shot thro the body and arms for God’s sake send me a Surgeon English if possible - if I do not recover God bless you all. J.F.’Last note written by Captain Joseph Fenwick, 3rd (The East Kent) Regiment of Foot (The Buffs), in his own blood — November or December 1810

Forlorn hopes

While all soldiers on active service will be mindful of the danger they face, most are ignorant of the fact that any given letter could be their last. As such, these final words often have an optimistic and carefree tone, or contain expressions of love and hopes for the future, sentiments which bring the tragedy of the author’s subsequent death into sharp relief.

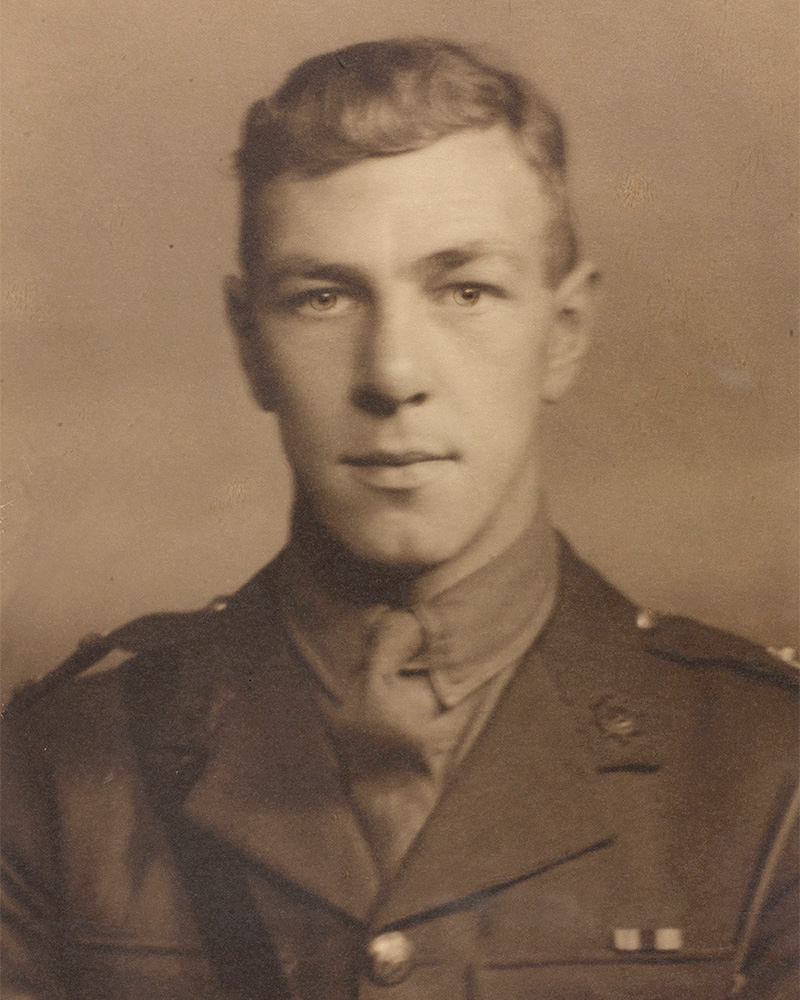

Lieutenant James Riccomini served with the 2nd Special Air Service Regiment in Italy during the Second World War (1939-45). He wrote to his wife, Jane, on 6 March 1945, just as he was about to embark upon Operation Tombola - a dramatic raid against a German headquarters in the Italian mountains - during which he would be killed.

Riccomini’s letter opens with a light-hearted story of drunken excess:

‘At last I have achieved my ambition yesterday we started drinking immediately after breakfast with the result that we were well away by the evening. To such an extent that I remember nothing between sitting at the bar & waking up to find myself in bed. However, it would appear that I put myself to bed, so that everything is all right.'

But he goes on to reveal his deep feelings of love and affection for Jane.

‘You do know Janey, don’t you, that whatever happens you will know that I have always loved you right from the time that I danced with a little girl in a mauve net dance frock… just remember that I do think of you very often & that one day I will be home again.’Lieutenant James Riccomini’s last letter, written to his wife before he was killed in action — 6 March 1945

Only in the event of death

Perhaps the most poignant of all letters are those written by soldiers to be delivered only in the event of their death. In these last testaments, the authors pour out their hearts, hoping to provide their relatives with comfort and solace through the sure knowledge of the love and esteem in which they were held.

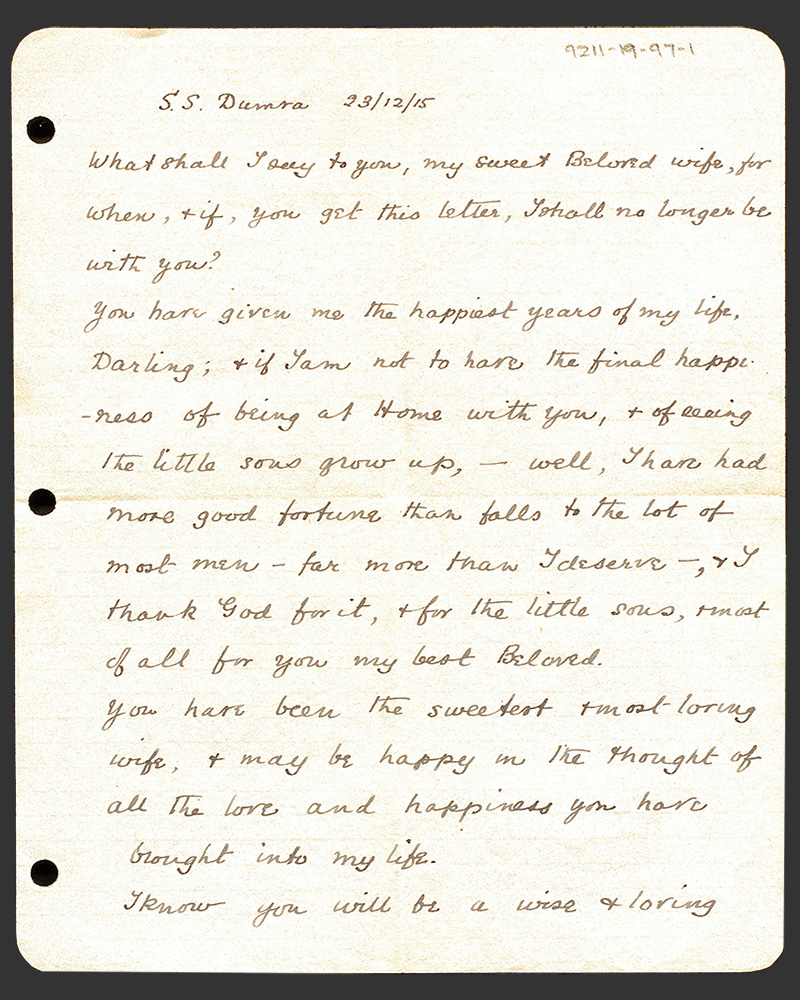

The most moving example in the Museum’s collection was written by Major General Sir Arthur Money to his wife, Euphemia, while he was en route to a new posting in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) in December 1915. In a heartfelt expression of love and affection, he remembered their happy times together and the great joy she had brought him:

‘What shall I say to you, my sweet Beloved wife, for when, and if, you get this letter, I shall no longer be with you?

‘You have given me the happiest years of my life, Darling; and if I am not to have the final happiness of being at Home with you, and of seeing the little sons grow up, - well, I have had more good fortune than falls to the lot of most men – far more than I deserve – , and I thank God for it, and for the little sons and most of all for you my best Beloved.

‘You have been the sweetest and most loving wife, and may be happy in the thought of all the love and happiness you have brought into my life.’

If delivered, letters such as these could become the recipients' most precious and treasured possessions. However, Money was fortunate that his letter never had to be read in the circumstance for which it was written. He survived the war and returned home safely to Euphemia and their children.

Sadly, many military families are not so fortunate as to enjoy such sweet reunions. The risk of death will forever be part and parcel of a soldier’s lot and, for their loved ones, so too will the corresponding threat of heartbreak and grief.

Access to the Archive

The National Army Museum provides public access to its library and archival collections via the Templer Study Centre. Over the coming weeks and months, we will be sharing more stories across our website and social media channels, highlighting some of the valuable personal insights these collections hold.